Friday, June 24, 2005

Gen. John P. Abizaid

June 24, 2005

U.S. General Sees No Ebb in Fight

By DAVID S. CLOUD and ERIC SCHMITT

WASHINGTON, June 23 - The top American commander for the Middle East said Thursday that the insurgency in Iraq had not diminished, seeming to contradict statements by Vice President Dick Cheney in recent days that the insurgents were in their "last throes."

Though he declined during his Congressional testimony to comment directly on Mr. Cheney's statements, the commander, Gen. John P. Abizaid, said that more foreign fighters were coming into Iraq and that the insurgency's "overall strength is about the same" as it was six months ago. "There's a lot of work to be done against the insurgency," he added.

His more pessimistic assessment, made during a Senate Armed Services Committee hearing, reflected a difference of emphasis between military officers, who battle the intractable insurgency every day, and civilian officials intent on accentuating what they say is unacknowledged progress in Iraq.

Mr. Cheney, in an interview with CNN after General Abizaid spoke, repeated his assertion that the insurgency was facing defeat, which he said was driving it to increase attacks to disrupt the United States-backed political process aimed at defusing the violence.

"If you look at what the dictionary says about throes, it can still be a violent period," he said in the interview. "The terrorists understand if we're successful at accomplishing our objective, standing up a democracy in Iraq, that that's a huge defeat for them. They'll do everything they can to stop it."

Persuading the public that the American-led effort in Iraq is succeeding is a White House priority this month. President Bush will meet Friday with the Iraqi prime minister, Ibrahim al-Jaafari, at the White House, and on Tuesday, he will give a speech on the first anniversary of the end of the American occupation.

Dr. Jaafari, speaking at the Council of Foreign Relations here, supported the White House argument that the situation in Iraq was steadily improving, despite continuing attacks. He also warned against setting a timetable for troop withdrawal. When he was asked Thursday evening about Mr. Cheney's recent comments, he sidestepped the issue.

Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld and his top commanders appeared at all-day hearings, starting with the Senate Armed Services Committee in the morning and continuing with the House Armed Services Committee in the afternoon.

"Any who say that we've lost this war, or that we're losing this war, are wrong - we are not," Mr. Rumsfeld said in the morning session.

He added that consideration of troop reductions in Iraq, as some Democrats have called for, would "throw a lifeline to terrorists, who in recent months have suffered significant losses and casualties, been denied havens and suffered weakened popular support."

General Abizaid had just returned from a visit to Iraq, Afghanistan and the Horn of Africa, where he said he was surprised at how many American commanders and soldiers asked whether the military was losing support at home for their missions overseas. "It was a real concern," he said.

He added that Afghan and Iraqi military officers had raised the same concern. "They worry we don't have the staying power to see the mission through," he said.

Several lawmakers warned that public support for the American troop presence in Iraq would continue to decline, which could eventually force a withdrawal of the troops, unless progress could be made at stemming the violence.

Senator Lindsey Graham, a Republican from South Carolina, told Mr. Rumsfeld at the Senate Committee hearing: "We will lose this war if we leave too soon, and what is likely to make us leave too soon? The public going south. That is happening, and it worries me greatly."

No senator called for an American withdrawal, but several Democrats urged the administration to consider setting a timetable for troop reductions if Iraqi officials fail to approve a constitution by a self-imposed August deadline, which could be extended for six months. The constitution is scheduled to be voted on in October, and if it is approved, a national election would be held in December.

"An open-ended commitment to the Iraqis that we will be there even if they fail to agree on a constitution would lessen the chances that the Iraqis will make the political compromises necessary to defeat the jihadists and end the insurgency," said Senator Carl Levin, Democrat of Michigan.

Dr. Jaafari urged the United States on Thursday night not to set a timetable for a troop withdrawal, saying insurgents would seize on the action to "spread terror across the nation to weaken the country."

He said the only viable military strategy was to wait until Iraqi troops are "trained to a very high level," a process he insisted was already well under way.

His reluctance to set deadlines appeared synchronized with the position taken by Mr. Bush, who has declined to set a goal for withdrawal.

Yet despite his care not to differ with the White House, Dr. Jaafari appeared at one point to side with General Abizaid, who told Congress that foreign fighters were still entering Iraq. Mr. Jaafari agreed that Iraq's borders were still not secure and that terrorists continued to flow into Iraq. He made no effort to quantify how many have entered the country, or how important they have been in the insurgency.

In the afternoon session, Representative Loretta Sanchez, a California Democrat, repeatedly pressed Gen. George W. Casey Jr., the top commander in Iraq, on whether the insurgency was in its final throes, as Mr. Cheney said, or was essentially holding its own, as another top American officer, Lt. Gen. John R. Vines, stated this week.

Pressed repeatedly to choose between the two, General Casey said: "There's a long way to go here. Things in Iraq are hard."

But General Casey insisted that the allied forces had significantly weakened the insurgency even though the number of attacks against American forces has remaining steady at about 60 a day for the last several weeks.

The most heated exchange of the day occurred between Mr. Rumsfeld and Senator Edward M. Kennedy. After a six-minute recitation of what he said were Mr. Rumsfeld's mistakes and misjudgments, the senator, a Massachusetts Democrat, accused him of putting "our forces and our national security in danger" and called for Mr. Rumsfeld to resign, as he has several times previously.

"Well, that is quite a statement," Mr. Rumsfeld responded, saying Mr. Bush has rebuffed his offers to resign twice.

David E. Sanger contributed reporting for this article.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections XML Help Contact Us Work for Us Back to Top

Paul Krugman

June 24, 2005

The War President

By PAUL KRUGMAN

VIENNA

In this former imperial capital, every square seems to contain a giant statue of a Habsburg on horseback, posing as a conquering hero.

America's founders knew all too well how war appeals to the vanity of rulers and their thirst for glory. That's why they took care to deny presidents the kingly privilege of making war at their own discretion.

But after 9/11 President Bush, with obvious relish, declared himself a "war president." And he kept the nation focused on martial matters by morphing the pursuit of Al Qaeda into a war against Saddam Hussein.

In November 2002, Helen Thomas, the veteran White House correspondent, told an audience, "I have never covered a president who actually wanted to go to war" - but she made it clear that Mr. Bush was the exception. And she was right.

Leading the nation wrongfully into war strikes at the heart of democracy. It would have been an unprecedented abuse of power even if the war hadn't turned into a military and moral quagmire. And we won't be able to get out of that quagmire until we face up to the reality of how we got in.

Let me talk briefly about what we now know about the decision to invade Iraq, then focus on why it matters.

The administration has prevented any official inquiry into whether it hyped the case for war. But there's plenty of circumstantial evidence that it did.

And then there's the Downing Street Memo - actually the minutes of a prime minister's meeting in July 2002 - in which the chief of British overseas intelligence briefed his colleagues about his recent trip to Washington.

"Bush wanted to remove Saddam," says the memo, "through military action, justified by the conjunction of terrorism and W.M.D. But the intelligence and facts were being fixed around the policy." It doesn't get much clearer than that.

The U.S. news media largely ignored the memo for five weeks after it was released in The Times of London. Then some asserted that it was "old news" that Mr. Bush wanted war in the summer of 2002, and that W.M.D. were just an excuse. No, it isn't. Media insiders may have suspected as much, but they didn't inform their readers, viewers and listeners. And they have never held Mr. Bush accountable for his repeated declarations that he viewed war as a last resort.

Still, some of my colleagues insist that we should let bygones be bygones. The question, they say, is what we do now. But they're wrong: it's crucial that those responsible for the war be held to account.

Let me explain. The United States will soon have to start reducing force levels in Iraq, or risk seeing the volunteer Army collapse. Yet the administration and its supporters have effectively prevented any adult discussion of the need to get out.

On one side, the people who sold this war, unable to face up to the fact that their fantasies of a splendid little war have led to disaster, are still peddling illusions: the insurgency is in its "last throes," says Dick Cheney. On the other, they still have moderates and even liberals intimidated: anyone who suggests that the United States will have to settle for something that falls far short of victory is accused of being unpatriotic.

We need to deprive these people of their ability to mislead and intimidate. And the best way to do that is to make it clear that the people who led us to war on false pretenses have no credibility, and no right to lecture the rest of us about patriotism.

The good news is that the public seems ready to hear that message - readier than the media are to deliver it. Major media organizations still act as if only a small, left-wing fringe believes that we were misled into war, but that "fringe" now comprises much if not most of the population.

In a Gallup poll taken in early April - that is, before the release of the Downing Street Memo - 50 percent of those polled agreed with the proposition that the administration "deliberately misled the American public" about Iraq's W.M.D. In a new Rasmussen poll, 49 percent said that Mr. Bush was more responsible for the war than Saddam Hussein, versus 44 percent who blamed Saddam.

Once the media catch up with the public, we'll be able to start talking seriously about how to get out of Iraq.

E-mail: krugman@nytimes.com

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections XML Help Contact Us Work for Us Back to Top

The Life

Inside the brothel, days and nights are an unusual mix of strict rules, camaraderie, and sex for money. Richard Abowitz gets to know the women of the Chicken Ranch.

By Richard Abowitz

? The Life

? Aspen's Journal

It is 5 p.m. on Friday when I arrive at what looks like a typical small-town saloon?a television is turned to sports and two guys are having drinks at the bar. But there are also about a half-dozen girls spread around the room. Two are playing a game of pool. A thin girl with blond hair arches her back just so, less, it seems, to make the shot than to display her?is the correct word G-string or thong? (I could be wrong; she sinks the ball in smoking style.) A thought passes through my head, and it's the first time I have ever surveyed a room with this kind of confidence, the sort that rock stars have: I can have sex with any girl in this room any time I want. It's an unbelievable high.

Five minutes later, Debbie Rivenburgh, 48, the general manger of the Chicken Ranch, gives me a tour. Debbie, for all purposes, is the boss of the Chicken Ranch, responsible for all the prostitutes, maintenance, security, staff and shift mangers. Everyone answers to her.

Despite the building's campy front fa?ade and porch, the comfy bar and the plush, spacious parlor where the lineups take place, I am surprised to discover that within its depth the Chicken Ranch is a maze made up of five double-wide trailers interconnected by wooden passageways and other rooms added on in what seems an architecturally haphazard fashion. The walls are decorated with glamour- shot photographs of working girls, some of which seem to date from decades ago. Another hallway has a series of framed Marilyn Monroe photos. There are also some watercolors, faded perhaps from years of hanging around low ceilings and hallways that can be thick with cigarette smoke. There is huge a kitchen with three large tables, a gym, more bedrooms for girls to work than I can count jutting off in all directions, a shift manger's office, and a larger office for Debbie in the back. Behind the brothel is a pool surrounded by bungalows and a fenced back yard.

"You are about to make history," Debbie tells me as she rounds up sheets and pillowcases for me. She doesn't say this with any pleasure. She has been employed here for 18 years and never before has a reporter been allowed to move into a working girl's room for a few days to live unmonitored by her. In fact, it is her day off and she is only here to orient me before returning to her residence, which is another double-wide, placed further behind the brothel.

Over the years this has occasionally made for a thin line between her life and work. "It is a complicated business to run and it consumes your life. My personal life has suffered. I've missed events when kids were growing up because my job had to come first." It's a balance she's better at now. She just completed months of taking care of her grandkids while her daughter served in Iraq. (She's instituted a discount at the brothel for veterans as well as those currently serving.)

She doesn't think she's unusual. "The people who work here could be your next-door neighbor, because we are. All of the staff that work here are Pahrump locals that are raising families. We are just normal people."

Debbie was never a prostitute?"I took this job working part-time as a shift manager as well as two other part-time jobs. I was a change girl at Saddle West, and I did dishes in a restaurant. That's how desperate I was for work ... After six months here it turned to full-time and now it's been 18 years and I still look forward to every day I come to work. Not many people can say that about their job."

Even in our phone conversations leading to my trip?which was arranged so the dates didn't conflict with her family obligations and took place after her daughter's safe return from Iraq?Debbie made clear that to her core she's a strong traditionalist when it comes to the brothel industry:

"The man who owned the Chicken Ranch started here in 1982 and he learned the business from the working girls who were here at that time who taught him the business. He taught me the business."

The Chicken Ranch is perhaps the most famous brothel name in the United States. The original Chicken Ranch has a history that goes back to the 19th century in Texas (serving soldiers from the Civil War through WWII, cowboys, and eventually the workers drawn in by the Texas oil boom). Though prostitution was always illegal in Texas, it wasn't until 1973 that the authorities moved to close the brothel. They succeeded in shutting down the Texas establishment, but the story memorialized in the movie Best Little Whorehouse in Texas made the Chicken Ranch name legendary, and a brothel owner in Nye County acquired the rights to that name for a legal brothel. Though Debbie isn't sure, she thinks some of the older paintings on the wall may be from the original Chicken Ranch in Texas. The current owner, Kenneth Green, purchased The Chicken Ranch in 1982. Next to Debbie's desk hangs a framed photo of the front of the Chicken Ranch back then: The road leading to the brothel is still dirt, there is no front porch. Green clearly knew it wasn't much to look at. Underneath the frame is a plaque inscribed: "Would You Pay $1.25 Million for this?" (Currently the brothel is for sale and though there is no sign out front, the prices bandied about are in the $6.1 million-to-$7 million range, though the publicist for the Chicken Ranch told me that the worth of the place has been estimated at $10 million.)

"Things have evolved over the years since then to a point," Debbie says. "But I am a creature of habit. When I'm told to do something a certain way I do it that way and I don't change the way I do it. I was taught in 1987 that this is what you say, this is how you do a lineup and I still do it that way."

And that's why although radio, television and the Atlantic Monthly have all passed through the Chicken Ranch of late, Debbie still focuses on the significance of my staying in a room that would usually house a working girl as "making history," and making history in general is not something of which Debbie is inclined to approve, particularly when it involves the press. "We have been burned again and again by the press."

Mostly, Debbie's view of press falls more on the side of public service rather than with a mind toward promoting the Chicken Ranch. For example, she frequently does interviews by e-mail with college students doing research papers. She tells me that the man who ran the place before her had the same policy.

But it isn't just press. Debbie will never be excited about doing anything new at the Chicken Ranch. Take the issue of cell phones. Until quite recently they were not welcome at the Chicken Ranch. "I did not trust all of the working women to not answer their phones if they had clients in the room. And that would have been a nightmare, just a nightmare. So we didn't let the working girls have cell phones while they were here."

So even years after cells became acceptable at other brothels, the Chicken Ranch still held out. "We had two pay phones, and one was an old phone booth so the girls could have privacy." But according to Debbie, the working girls' constant complaining eventually reached a fever pitch. "They said they needed their phones to keep in touch with their families and check up on their children and all these different reasons."

Debbie was at last convinced. After much thought and discussion (about 18 months ago), a perfect solution was reached. In the shift manger's office, Debbie points to a series of little wooden cubbyholes against the far wall of the office. Each wooden box has a room number.

"We decided that we would let them keep cell phones. But when they book a client they have to check the cell phone. And they can pick up the phone when they are through with the party. It works, and we don't have to worry about the more immature girls wanting to answer their phones and talk to their husbands and boyfriends while there are customers around. It's working and I'm amazed."

Even when it comes to something as potentially profitable as setting up the website for the Chicken Ranch, the brothel was slow in coming to a decision. Debbie recalls:

"I know when the Internet started to be a big thing and people all started to get it in their homes, me and the man who taught me the business were reluctant to engage in having a website. We were old- school, and we held back because we didn't want to venture into that area because it was something we didn't know, and we were afraid of it. I know some of the other brothels and we were hearing that it was helping increase their business because guys could research. So we reluctantly gave in and got a website. I have noticed a vast change in business."

It was more than Debbie's temperament that accounted for the reticence, however. The brothels in Nevada are the only legal ones in the United States, and they exist because of the Silver State's unique history and quirky traditions. The truth is, all they have is that past; there is no guarantee of a future. Debbie fully realizes this. "Is it ever going to be legalized anywhere else? Probably not. Most people can't see past 'prostitution'; it's such a bad word." And therefore, time is likely not on the side of the Nevada brothels and particularly those near Pahrump.

When Debbie arrived in Pahrump in 1987, the population was about 3,000. It's now a town of over 30,000. The week after I left the Chicken Ranch?in what the Review-Journal reported to be one of the largest crowds ever to show up at a Pahrump Town Board meeting?a motion to lift a ban against brothels within Pahrump city limits to allow the annexation of the tiny bit of Nye County that includes The Chicken Ranch and neighboring Sheri's Ranch, was rejected. The town board member who sponsored the brothel amendment is quoted in the paper as estimating that this would've meant about $13 million over the next decade for cash-starved Pahrump; probably more tax revenue than any other business in the town. Though the bill would have created no new brothels and there was a common-sense financial benefit to making this annexation, Pahrump's citizens didn't want to have as part of their city the same brothels that were already a long-standing part of their community.

It's not an isolated case.

The Nevada Legislature just approved a massive new entertainment tax on topless strip clubs and, despite the brothel industry's lobbying efforts, the legal prostitution houses were exempted from the tax. On June 10, the R-J's John G. Edwards, reporting on the bill, noted, "Legal brothels, which operate in places such as Pahrump, will continue to avoid the entertainment tax even though a brothel-industry representative asked that brothels be included." In the history of the United State has there ever been another industry that has lobbied to pay more taxes? And that's the rub?the nation's only legal brothels exist always a vote away from extinction, with only a long tradition to protect them in a fast-growing community like Pahrump, with increasingly fewer people connected to local history. It can't be a good thing when politicians are scared to tax you.

I ask Debbie if she feels the days of legal brothels in Nye Country are numbered.

"I think they will stay legal into the future, but how far into the future I don't know. As this town grows and you have your younger families raising children moving to town, you're hearing more and more opposition to us being here. But we stay down here where we're at, we don't abuse the emergency services in town?I have been here 18 years and I've never once had to call the sheriff's department to assist us. We like to be a good neighbor to the people who live down in this area. As long as we continue to stay down here, be good to the town and don't bother anybody, then we'll be OK."

So while the brothels near Reno?where the population boom is far less extreme and threatening to the legality of the brothels?have been active in courting publicity, porn-star appearances and, these days, even presenting the occasional reality television fodder for cable, things have stayed far more traditional in Southern Nevada. And that's especially true at the Chicken Ranch.

? ? ?

This desire to stay on the lowdown is also perhaps a significant factor in what everyone agrees is the most onerous practice of brothels in Nevada, the lockdown. Lockdown is custom, not law, and it is practiced primarily by Southern Nevada brothels including the Chicken Ranch and neighboring Sheri's Ranch.

During the periods the women work?which can last for months at a time (the minimum stay at the Chicken Ranch is 10 days with girls always spending the first few days unable to work until STD test results arrive from a clinic in Las Vegas)?prostitutes are not allowed beyond the gates that enclose the brothel. Debbie admits that lockdown is hard on the girls:

"People tend to lose sight?and even I tend to lose sight?in the day-to-day grind, that they have lives outside of here. To completely leave your life and go be locked up in a place for a couple weeks at a time, well, your personal life doesn't come to a standstill."

The girls are more blunt in referring to life under lockdown as "pussy prison."

The only exception to lockdown is on Tuesday, dubbed "Doctor Day," where the girls are allowed into Pahrump on their own for no more than four hours?divided into morning and afternoon shifts so there are always women available for customers back at the brothel, which is open 24/7. But even on this day there are limits. First off, at least an hour of that precious time away from the Chicken Ranch is spent at the doctor's office getting more STD tests.

Unofficially, the girls are discouraged from going to casinos, hotels and any other high-profile place or places they could conceivably ply their trade outside of the legal confines of the brothel. They are also asked to dress modestly and behave appropriately.

In fact, the brothel management, according to a few working girls, is so nervous about the weekly outings to Pahrump that according to one girl, "That pretty much just leaves Wal-Mart, the grocery store, the gas station and fast food as the places we can go." On the Doctor Day I am there, despite having spent a week straight bottled up in the brothel, all of the girls who went out that Tuesday morning returned more than an hour before curfew. There just isn't much they can do in Pahrump.

The tour ends in front of my home for the next few days. Room 7 is a Spartan affair with a bureau, a mattress hoisted up on four cinder blocks next to a small nightstand, the lower drawer of which?where the Gideon Bible would be in a hotel?is filled with medical waste bags to dispose of condoms. The carpet has that meaningless gray-tan color that would be immediately recognizable to apartment renters in Las Vegas. There is a television with a reading lamp placed next to it. I figure they are being thoughtful, knowing that as a writer I will be making use of the lamp. I put it on the nightstand and adjust it to reflect on my notebook, thinking it pretty convenient. It is only the next morning that I learn the lamp's actual purpose: the girls use it to perform dick checks on customers to make sure they have no visible signs of an STD.

I share a bathroom across the hall with T. and any of T.'s customers who want to use it. She's a tall blond in her late 30s who is completing the testing for a regular job in the medical field and wishes to be identified only as T. There are nicer rooms with faux-wood floors, and one I saw even had a private bathroom. But those are for the girls who are regulars. My room is meant for the more transient girls. And while there is certainly a lot of turnover in a business like this one, there are also some surprisingly long-term working girls employed at the Chicken Ranch. One tall blond who can't yet be 30 has been living here more or less since 1997, and every morning she walks the brothel's dog, Heidi, and pays for and feeds the brothel cat, Meow Meow.

After showing me to my room, the first thing Debbie does is call a mandatory meeting to introduce me to the working girls and staff and to make sure everyone is aware that I will be around reporting a story. They have just finished dinner?meals are served at noon and 5 p.m. and so the gathering takes place in the kitchen. A few days earlier, Debbie told me over the phone about the considerable effort and time on her part it took to prepare the girls for my arrival. She said it wasn't easy. The girls were used to the routine under lockdown and having anyone?but especially a man?stay over at the house was very troubling to some of them. So Debbie's regulations seemed compiled more to meet the concerns she heard from those girls along the way than to protect the brothel from my snooping. She gives us all a handout labeled "Richard" with a dozen rules. Typical among them:

"Do not listen to or include in your article any private conversations between working girls."

"Do not enter the working girls' bedrooms unless you are invited by one of the interview participants."

"Above all, respect the privacy of the women who are not participating with you."

Even the girls who had appeared to be party animals (who I am introduced to as Trinity and Diamond) in the bar just a few moments before are now fully focused employees paying close and sober attention. It turns out, there were no fast times going on in the bar, anyway, at least not when I got here. The scene I had witnessed in the bar when I arrived at the Chicken Ranch was nothing more than a "barlor," a display of the wares meant for the two men who had been sitting watching the television. ("Barlor" comes from "bar" and "parlor".)

When the customers request a barlor, the working girls must all file into the bar and introduce themselves, and after that comes the awkward period when the men must make some decisions for things to go forward. The decision of which, if any, girl to choose is one I soon learn guys love to agonize over and put off making. During the next few days I will see countless barlors and they tend to all end up like a bad high-school dance: boys on one side of the room, girls on the other. After introductions, the men tend to talk among themselves and the girls must wait to be asked back to their room, and so amuse themselves by playing pool or sitting together chatting. Some girls resent this waste of time since so many men arrive simply as gawkers.

Photo by Benjamen Purvis

"I don't really like barlors," Eden tells me. "Unless there is a barlor, most of us who don't really drink much never go in there." (Eden has great hair and a lovely face and no illusions about her number-one selling point, her chest: i.e., her website address, Eden38dd.com). Eden explains that she tends to prefer the more traditional lineup that, while somewhat more demeaning, involves less socializing and works better for keeping the customers from procrastinating. Actually, it isn't too long after Eden and I start talking that I get to go see for myself, as the bell rings to signal to all the girls in the house that a customer has arrived for a lineup.

There is nothing more ritualized and traditional at the Chicken Ranch than the lineup. The customer or customers sit on thick, comfortable sofas while the girls all crowd in the hallway adjacent to the parlor, around the corner, passing back intelligence reports on the age, nationality and whatever other details of the men become available from sneaked glimpses.

"Ladies you have a visitor," the shift manger says. And, with that, the girls file out and stand single file in a row in front of the sofas. A curtain covering the back wall parts, revealing a mirror behind the girls that allows customers a rear view. Each girl introduces herself, but is not allowed to say anything else. As in the barlors, customers tend to not want to make up their mind, and that can be agonizing for the girls who must stand half- naked (and, if it is late enough, half asleep, too) fully displayed. The girls try to hide their discomfort and smile and project a sensual attitude, but it is hard for them not to inwardly groan when, as usually happens, the customers will stall for time with something like, "Wow, they are all so lovely. Can I have all of them?" Mostly, the girls are good-natured enough to laugh as if amused by this line they hear every day. If the men take too long, it is up to the shift manager to nudge things along with "Are you ready to go back with one of the girls now?" or "I really can't have them just keep standing out here like this. Is there someone who you would like to spend time with?"

After being picked?either by lineup or barlor?the girl then takes the customer back to her room to negotiate money. Though the menu of available services itself is posted on the website ( www.chickenranchbrothel.com), it is without prices since the working girls are independent contractors and they fix their own rates. One of the few truly sensitive areas to both the brothel and the working girls is the discussion?to be blunt?of how much specific sex acts cost. The truth is, even for the girl the amount can vary. A customer can strike a better deal during a slow time than during one that is busy. The problem is that it's almost impossible for a customer to know which times are busy and when things are slow.

On Saturday night I ask the shift manager when the rush begins. "Who knows?" she says. "This isn't a nightclub." And that's true. Saturday night turned out to be far quieter than Saturday afternoon, when the bell rang over a dozen times before noon. Monday evening seemed busier than Saturday night. Who would've guessed?

Diamond, Trinity and T. call themselves the three musketeers. All sexy and ready do business on Saturday night, instead they sit crashed out together on the couch watching three movies in a row on the Lifetime channel. According to Trinity: "We also watch Jerry Springer and every day at 2 there is our soap opera, Passions." I could be wrong, but based on their dedication, my guess is there will be no discounting from these girls when Passions is on.

Over my time there I am stunned at how cheap guys can be. Especially, since?and, of course, there is no way for customers to know this?behind the scenes every little difference means more than you think to the working girls. I am sure it has to do with the deeply personal nature of what they are selling. But there are probably no other workers whose income can easily enter the six figures annually whose personal happiness is so much increased by performing an act for $600 instead of $500. The girls don't use the word "date," preferring "party," and if you kick in the extra hundred it really does make the girl feel more like she is at a party.

Interestingly, no girl would admit to performing the act differently or more enthusiastically on account of money. The sex a girl provides for $800 would be little different than the sex for $400 (if you can get her to agree to it). In short: halfhearted sex is not for sale at a discount. During my time at the Chicken Ranch the range was extraordinary, with deals cut that ranged from $200 to $3,000 (for a bungalow). All of this money is split 50/50 with the brothel. The girls must also pay $30 room and board to the brothel as well as pay for their own medical testing (about $60 a week) and even provide their own condoms. So in general, the girls who make the most money are doing it through volume rather than a few high rollers. According to Eden, "I don't have notches in my bedpost, because at this point my bedpost would be shredded to a toothpick."

Still, making the girls' happy isn't the only reason to err on the side of bringing too much money to the Chicken Ranch if you go, because not having enough can mean a long, wasted trip from Vegas. Amazingly it happens all the time. On Saturday morning at 7 a.m. a man paid $150 to arrive by taxi from Vegas, only to not have enough money left for what he came here for.

By my estimate about half of the men who actually go back with a girl wind up leaving because they are unwilling to reach an agreement. Often though, the deal-breaker isn't money but the customer wanting an activity that is either banned by law (oral sex without a condom, for example) or something that the girls refuse to do, according to Eden: "For most girls it's: no kissing on the mouth, no fingering, and don't bite me."

Still, according to Eden, customers tend to be respectful. Eden says of the typical customer: "I would say generally it is 35- to 65-year-old professional men. It is a demographic of people with the disposable income and that generally is pretty nice guys."

A marketing major a few credits shy of graduation, Eden explains her approach to prostitution as a mix of entrepreneurship and post-post-post (hell, this kind hasn't even started yet) feminism. "I go about it as a business. I am a smart girl and I am an attractive girl so I know I can do many, many different things. But this is fulfilling an aspect of my sexual life. Most people don't embrace their sexuality for all it's worth. If you are a sexual person, you enjoy all the aspects of sex, the different things. Just because it is not mainstream doesn't mean it's wrong. Sex is such a crazy thing. Whatever is enjoyable sexually is in the mind and body and spirit no matter what it may be. And I am just a very sexual person and I am making a business out of it. Would I be doing this for free? No!"

Eden, of course, realizes she is an exception and this job is not always the career of first choice. "Lots of girls that do this line of work aren't good for anything else. I don't know how to say it without being politically incorrect, but this is all they can do. They are out here because they have no home, no place else to go. They have nothing. This is all they are good for. That seems very sad. But I also think they have the potential (because of the amount of money they earn) to do so much more with themselves but they opt not to do it. They are doing what they want to do with it and so I don't criticize them."

In a society where being a model for Playboy has become a status symbol of the highest order, most of the adult entertainment jobs that used to be a lifetime stain are now acceptable (two weeks ago a former stripper was elected to a judgeship). Also, to a large extent, strippers and even porn stars are now glorified by the mainstream media. But prostitutes are the day laborers of the sex business. The cultural status of a prostitute is as loathsome now as it was 20 years ago and the workers at the Chicken Ranch feel it acutely. And for all her independence, her pride in her ability to earn money and to manage her career and, most of all, to be exactly who she wants to be, even with all of that, Eden feels the sting of society's disapproval:

"In general with everything else I don't care what you think. I don't care what you think about what I look like; I don't care what you think about the way I dress; I don't care what you think about my car; I don't care what you think about me in any way, shape or form whatsoever. But yet when it comes down to this I don't tell people. Instantly, no matter how good a person you are, no matter how religious you are, what a good mother you are, what a good cook, no matter what it is you do that you are excellent at, at that point that you tell someone you are a prostitute you become a scum of the Earth. In general you are instantly degraded for that to the bottom of the barrel."

So why would Eden?so smart and capable?choose work that generates such hostility in the outside world such that even someone as fearless as she is balks at mentioning her work to people? "There are three factors. What order they go in, I don't know. It varies day by day. To me money is a factor, to me being able to use my sexuality in a positive way for me appeals to me, too." She then turns silent for a full minute. I can see in her face that she is struggling for a way to express the third factor, and I try to imagine what it could possibly be and draw a blank. When she starts talking again it is without her usual lucidity. Her sentences start, then stop, then try again. Yet this is clearly the most important thing of all to her:

"Third, um. Then probably third. Probably." There is another long pause. "I can't tell you how wonderful it is to have somebody thank you for being so nice to them and making them feel so good ... um ... making them appreciate life again. I mean, I have had someone say to me that coming out here ... Someone can enjoy themselves enough to go back to appreciating life. I have had someone say something that deep to me. Sometimes people come out here and you personally create a life-altering experience for that person. That to me is very rewarding."

This is Eden's story of that customer:

"A gentleman came out here. He was probably about 60. We went back and I gave him a menu. He says, 'No, this is going to be a special situation.' I'm like, 'OK, just talk to me.' He proceeded to tell me it was the two-year anniversary of his wife dying of cancer. Since she had passed away he had not been able to get past the fact that he loved his wife and that she is gone. He had not been able to have any relationships or to allow his life to move on because he had this guilt. He said, 'I am trying to make my life go on and to believe that just because my life goes on I don't love my wife any less. I picked you because my wife had red hair and was built like you. You actually resemble her. All I want you to do is just lay here next to me and let me hold you. I don't need you to talk to me or do anything. I just want to lay here and hold you and think of you as my wife and think about how much I loved her and what she felt like to me. I just want to say my good-byes to the only woman in my life.' We had no sexual contact whatsoever. He lay there for an hour and he held me in a spoon position, and he just cried. It took everything I had not to wail, but I figured that I couldn't break down because I was there being strong for him."

Eden kept in touch with the man until he sent a final e-mail telling her that he was remarrying and thanking her for helping him begin to move forward.

The girls frequently develop friendships with customers that can be hard for an outsider to fathom. One of the few customers willing to talk to me was Ernest, 37, of Las Vegas, a contractor with sandy blond hair standing about 6 feet 2 inches tall with a bit of a belly. He was Diamond's friend though not her customer?well, not exactly. "I don't party with her," Ernest says. "I did a two-girl party once with her and she was in the way and so technically I never partied with her. She's not my type." Rather Diamond is charged with picking the girl for Ernest to party with.

Ernest and I are sitting at the bar discussing this while watching Diamond and Trinity play pool, and Trinity is topless, because those are the stakes, and she is losing. As Diamond had told me earlier, "Sometimes we have drinks and play pool and wait for guys to come in. I always beat her. Trinity is a good friend but a bad pool player."

"Would you party with me?" Trinity asks Ernest.

His diplomatic answer: "I would have fun, but you probably wouldn't be my type."

"I knew it!" Trinity says.

I ask Ernest: "What's your type?"

"I'll tell you," Trinity says. "He likes a little bit of an older woman." Trinity is 21. Diamond is 25.

"Is that true?" I ask Ernest.

"I tend to enjoy myself more with the older women."

The women here today range from 21 to 41.

Ernest recalls his first trip to Chicken Ranch: "I'd been divorced for awhile. I hadn't been with anybody and so I decided to come out here. I was certainly nervous. I did the lineup. I've only done one lineup and that was the first time." That was about a year ago. These days he drops by a couple nights a week.

Two more men come in for a barlor and the room fills up suddenly with girls. I ask Ernest how many of the girls now in the room has he partied with? He surveys the area and then to my embarrassment he points and starts counting out loud like the Cookie Monster: "Um, 1, 2, 3, let's see, ah, 4, 5, 6. I guess around 7."

Ernest uses all of the clich?s to compare the brothel experience to the dating world: "The cost is about the same. I am serious. I am a numbers person, and I've gone through the numbers. I justify it. Here if I go back with somebody, I am going to be going back with somebody who I know is clean. That's the main thing. But the other thing is that I get what I want. I usually get treated really well. I feel comfortable with a girl when I go back with her. There have been a couple times when I partied with a girl and I would never party with her again, but I never felt cheated. They are courteous. I feel like I am at home out here. Everyone treats me like part of the family." But Ernest's popularity has not come cheap: "Since December of last year I've spent about $12,000." Still, not every visit is a party. "Sometimes I go months without a party."

"Are you going to party tonight?" I ask him.

"I haven't decided yet," he says. He sips his beer, not taking his eyes off Diamond.

"When do you make the decision?"

"When the mood hits me. And who knows when that will be?"

Ultimately, the mood hits Ernest, and Diamond picks the third Musketeer, T., for him. "I picked her because she is an older woman and I thought they would have more in common than someone my age and that would make him more comfortable. I know what he likes and doesn't like," Diamond says.

The friendship between the girls themselves is less complicated and in many ways more intense because they live together in such close quarters for such extended periods of time. When I arrive, for example, Diamond has been working at the Chicken Ranch for over three months straight. "The first two and half months were a piece of cake, but now I am starting to get a little crazy. Sometimes I am not in the mood and sometimes I get irritated fast." It is a position few could understand and this is how she defines the Three Musketeers:

"A couple girls came in and I got attached to them. We kind of hang out together, drink together and party together with guys. And of course, we watch movies on Lifetime. When you are down and out they are like family who are in the same business. They can tell you how to get through it. And we can be there to give each other support. It is a bond that we make between us three."

But even among the girls who don't seem particularly close there are surprising relationships. Eden and Diamond appear polar opposites. Think what you want of her work; Eden is sophisticated, thoughtful and articulate. Diamond is brash, tough and has a street education that at first appalled me with some ignorant comments she made about HIV positive people. I never once saw Eden speaking to Diamond or to any of the other Three Musketeers. I didn't see Eden so much as glance at the television that Diamond seems to watch with every free moment of time available to her. I thought of them as residing in different universes even within the limited space of the brothel. I assumed in fact that they probably did not even like each other. Even Debbie remarked at the contrast: "Diamond is more a little-girl personality whereas you have Eden who is more serious."

Then one night Eden takes me aside:

"This is going to surprise you. But you would never guess that one of the girls I am closest here with is Diamond. It surprises me. We are so different. I don't think we would have ever become friends if we had met outside of here. But we share a bathroom here and we are both neat freaks. She and I both tend to earn a lot of money and so there are occasionally jealousy issues with other girls. We have that in common. I am picking her up at the airport when she next flies out next time, and she is spending the night at my place."

The friend I see Eden spend most of her time talking with is Aspen. Eden, in fact, talked Aspen, whose previous work experience was as a sixth-grade teacher, into coming to work at the Chicken Ranch. "Yes, I recruited Aspen," Eden admits with a laugh. "She is a personal friend of mine back in Vegas, and once I got to know her I figured out she was very open, very nonjudgmental and very sexual. I had been telling her I was a stripper when I was actually out here. But when I got to the point that I was comfortable with her and I told her what I did, she thought it was really neat. And at that point we talked openly about it, and she thought it would be interesting to try and do just for the experience. So she came out here with me in January and really liked it."

? ? ?

It was Aspen who wound up being picked from the lineup to take care of a severely handicapped 32-year-old man whose parents took him to the brothel. I found out from Eden later that the father? on vacation from Florida and who I couldn't help notice was bedecked in gold neck chains that suggested finances were not a serious issue for the family?lowballed Aspen on the price. While Aspen was with their son the parents watched television in the bar. Their son had very limited use of his hands and feet and as the parents worried that Aspen would charge more to dress him afterwards, they suggested she send for them when she was finished so they could put his clothes back on.

"His parents told me what he wanted," Aspen explained to me later. Aspen thinks the man was probably a virgin though she is not sure. "He told me, 'I don't have a girlfriend. I probably won't ever have a girlfriend.' So, I really, really wanted him to have a good time. I wanted it to be a very good experience for him so he would have that memory."

"Eden told me you weren't paid very much?"

"No I wasn't."

"She said it was the lowest you could take."

"Well, yes, but ..."

"But nothing. I saw the chains around the dad's neck. That family could have paid you a lot more."

Aspen sighs: "I gave them a range and they went to the lower end. But they weren't asking for anything outrageous and he was very nice, a very bashful man. The parents wanted me to come get them to dress him. But I thought if I could undress him I could dress him again. I just thought it would be more comfortable for him if I did it. And I did it. It was no problem."

"And you didn't mind going the extra mile for people who didn't want to pay you a penny more than they could get away with?" I ask.

Aspen waves her hand dismissing the notion and then she says: "I think he probably has the heart of a trouper himself. In some strange way I was grateful, because he reminded me of my husband."

It is one of those many moments at the Chicken Ranch where expectations, preconceptions and everything else explodes. "Excuse me?" I ask.

It turns out that Aspen is a widow. "My husband wasn't quite like that, but after he had a stroke he lost a lot of the use of the left side of his body." Aspen took care of her husband for three years like that before he passed on in 2001. Because she is widow of a man who knew he was dying, Aspen was taken care of financially to some extent. She is one of the few girls at the Chicken Ranch who is definitely not there primarily for the money. She too is seeking to explore her sexuality, though she does admit to earning good "furniture money" for her house.

Over days living with the working girls if I formed one real bond, it was with Aspen. I tell Debbie that Aspen is the sort of person who I would be friends with in the "real world." It is the truth. Aspen and I spend hours talking and very little of it winds up being about the Chicken Ranch. We both like Edgar Allan Poe, can spend an afternoon discussing Shakespeare, have an interest in biblical scholarship and enjoy debating philosophy. We get each other's taste enough to recommend books to each other. Not that we are identical. Aspen enjoys karaoke and has a fondness for Meatloaf's singing that I find hard to abide. But one night, sprawled on the floor of Aspen's room listening to Dylan's Highway 61 Revisited (someone has to save her from a life of Meatloaf fandom) I feel exactly like I am back at my college dorm hanging out in a friend's room. When the bell rings for a lineup it is a shock to be reminded that in reality I am sitting in working girl's room in a brothel in Nye County.

Yet, as diverse as all the working girls I meet at the Chicken Ranch are, I do notice that there are some similarities. Aspen is not alone in possessing a nurturing personality. Even Diamond, when asked what she would like to do if she could choose any career answers without hesitation: "My dream is to go to college so that I can be a nurse." This desire to take care of people is perhaps the greatest vulnerability the working girls share. And it is exploited.

Many of the girls have boyfriends and husbands and about the only common denominator among them: None of the men in their lives seem to have regular work. Of course, one has to be careful about stereotyping; there were many working girls at the Chicken Ranch I did not speak with and some girls I did interview chose not to discuss their private life at all, a decision that was respected. Some girls put up a valiant fight, too, claiming that their man was needed to watch children (as if millions of single parents don't pull that miracle off each week and work, too) while they were under lockdown, or that he was engaged in crucial home- improvement projects that otherwise would need to be paid for by a contractor (another feat pulled off by millions of working folks who keep the registers at Home Depot humming), or, perhaps, he is needed to handle the time-consuming task of paying bills and running the business affairs for a girl while she was at the Chicken Ranch (all of which can be done from the brothel thanks to phones and Internet access, not to mention: How could the few things left be too much to allow time for a job?). There were other answers, too. All foolish.

I tell Debbie that I have noticed a pattern. "That's just part of life and you can't judge them for that," Debbie says. "I learned early on that there was part of me that just needed to understand. If there was a girl who was willing to discuss her personal life with me she had to take whatever feedback I had or whatever questions I wanted to ask. But I gave up asking those kinds of questions, because there is always a reason. To me, 'Why does he not he have a job?' you just take as part of the business. And after awhile you just don't pay attention to it anymore, it just doesn't faze you."

And, when Debbie says she doesn't judge the working girls, she means it. She stops me cold when I offer my theory that on some level the answer to why men are able to accept their girlfriends/wives working at a brothel is that they are living off the proceeds. "That's a difficult area," Debbie interrupts. "I am not going to try to figure it out. I gave up trying to figure it out. There's a lot of things I gave up trying to figure out years ago and that's one of them."

Trinity is one of the few girls who is single and so is willing to discuss it. I ask her about the dismal employment rate among the partners of working girls. "Pretty much, yeah. A lot of times the other half chooses not to work because we woman make enough. We make a lot of money." Trinity estimates her monthly income at $9,000 to $12,000 a month. Another girl tells me she shoots for $500 for each day she works. Another is preparing to leave after an extended stay with close to $40,000 saved.

Of course, only the more successful girls are willing to talk to me about their earnings, and there are plenty of whispered horror stories of women who don't earn enough to cover their room, board and bar tab (girls drink if they want to, but not to excess). Not making enough to cover those bills, by the way, would be a good hint to get out of the business. Even Aspen, who is a relative newbie with only a half-dozen trips to the brothel (most lasting only a couple weeks) has had just one day when she did not have at least one customer. Few jobs make it easier at giving you the news that it is time to stop. It is certainly true that I had less sex?none, yeah, you needed to know, didn't you??than any other resident in the history of Room 7 at the Chicken Ranch.

But one thing my time at the brothel taught me is that nothing is straightforward, no judgment fully comfortable to make once you allow yourself into the details of a brothel's reality. Even something as seriously twisted as lockdown occasionally has strange benefits. Debbie points out: "I've seen girls come here who have a pimp. They come here and they start to get a clearer picture of the controlling abuse and the negatives that guy is having on their life. Because they are away from it and they can see it. And the girls support each other when and if they are fed up with the man. I've seen that a lot."

Of course, one person's idea of a pimp is another person's spouse and the distinction can be a very slender one in relationships where the man produces no income. Besides, lockdown can place significant stress on even the most stable relationship. Eden and Aspen (who met the man she lives with now about a year after her husband's death) have both been with the same partner for years. But they admit the topic of whether their boyfriend cheats during the weeks while they are out at the Chicken Ranch is one they can't stop talking about with each other. And Eden and Aspen both have seen plenty of cheating husbands at the Chicken Ranch. Both, of course, tell me that they are sure their man isn't a cheater, though Aspen seems to have more conviction on this point than Eden.

But mostly it is the little indignities of lockdown that are so hard on the girls; even meals take on ridiculous importance. Debbie puts it this way:

"I try to impress upon a new cook how important meal times are to a girl, because of the fact that they are locked up in here, they look forward to their meals. That is the one thing that changes every day in their life."

Debbie's mom Joan is a cook, and says, "Out here they like spaghetti. They like meatloaf with mashed potatoes and gravy. They like fried chicken and Mexican. I cook for them like I cooked for my family." Many girls also snack from one of the stocked refrigerators, and all say they gain weight at the brothel.

Still, while it seems trivial, Diamond and Trinity got very excited Sunday afternoon when I offered to bring them back whatever they wanted when I decided to make a run to Subway. On my way out I remembered one of the dozen rules was "Check in with the shift manager anytime you want to do something not covered here." So, thinking it routine, I asked at the shift office when I went to be buzzed out of the gate. Debbie wasn't around, and there was a change going on in shift managers. Standing with them was an office employee. But when I asked about bringing back some subs an intense three-way conversation broke out (one shift manager was inclined to say yes, and the other no with the office worker firmly disapproving to shift the balance). Permission was denied. Still in shock I find Diamond, who didn't seem at all surprised by the decision. "Don't worry about it. Don't get yourself in trouble," she tells me.

This is typical of the flip side of lockdown. Whatever the legitimate arguments for the practice, the prostitutes at a brothel on some level should always be treated as adults who are at work. Yet a shift manger has it in her power (they are all women) to treat an employee more like a prisoner than an independent contractor who is residing at her work location. The humiliation of this sort of treatment can sometimes be staggering to outsiders. I can almost see the sign on the cage: DON'T FEED THE HOOKERS. The power that brothels wield over the working girls who reside there can land in ways that are as overwhelming as they are arbitrary.

In the end, I smuggle back a contraband Subway sub for Diamond and Trinity to split.

? ? ?

My time at the Chicken Ranch was clearly coming to an end, and not just because I proved unable to follow the rules for more than a few days. On Monday a new batch of girls arrived for quarantine and Debbie had not prepped them for a reporter living at the Chicken Ranch. Their hostility was palpable. For the girls who had existed under lockdown for days straight before I arrived that Friday afternoon, having me around had turned out to be a novelty, but for these new girls, having a guy in one of their rooms was a distraction at best and at heart seemed to throw off the balance of their private space.

I realize now that Debbie had not been exaggerating when she spoke about how much effort it took her to get the working girls to be OK with my being at the Chicken Ranch these few days. It probably didn't help that a girl who has been assigned to Room 7 was being forced to live in a bunk bed (she was quarantined still, and could not work so didn't yet need the room) in another room while waiting for me to vacate so that she could set the place up as she wanted it. Though I had agonized about if it would be perceived as rude to bring my own sheets to the brothel (ultimately deciding not to do so), most girls bring way more than sheets; they completely personalize their rooms from the drapes to the art on the walls.

So on Tuesday morning I pack up my stuff to vacate. It is Doctor Day and Eden, Aspen, Trinity and Diamond all are on their morning excursion to Pahrump. I decide to wait for them to return to say farewell before leaving. But just as they get back my friend John arrives at the brothel with a friend of his I don't know. We are all sitting in the bar when the unthinkable happens; he starts to behave like a customer, and not one of the nicer ones. First he demands a tour of the brothel. Then after ordering a drink he begins to crack witticisms like, "How much would you charge to let me fart in your face?" Having already introduced him as a friend I decide the only thing to do is just slink out the door like anyone in the midst of a shame spiral. And I make it as far as the front porch when Aspen calls me back to the door of the parlor she has raced around the bar to get to in order to catch me before I escaped beyond the gate, outside the range of her lockdown.

"Hey, don't sneak off. It's fine about your friend. We get stuff like that all the time. Maybe you'll write something that helps people understand us better."

"I am really sorry about John."

She reaches over and pulls me into a quick hug. It is my first physical contact at the brothel. We say nothing for a moment. We are both looking over at Meow Meow, who is making a rare afternoon appearance on the porch where her food bowl is kept under a chair. Inside, I can hear John's laughter. He borrowed some cash from me before I left (an accident in Southern Nevada took out the ATM that morning so he can't use his card) and I wonder if he'll wind up spending it. I feel bad keeping Aspen since I hope she gets his money as much as anyone. They all deserve it for putting up with him. "What a strange way for your story to end," she says

"No," I tell Aspen, "This is the perfect ending."

I reach over and hug her back and then head to my car

Las Vegas Weekly. All Rights reserved

Illustration by The New York Times

June 24, 2005

An Army of Soulless 1's and 0's

By STEPHEN LABATON

WASHINGTON, June 23 - For thousands of Internet users, the offer seemed all too alluring: revealing pictures of Jennifer Lopez, available at a mere click of the mouse.

But the pictures never appeared. The offer was a ruse, and the click downloaded software code that turned the user's computer into a launching pad for Internet warfare.

On the instructions of a remote master, the software could deploy an army of commandeered computers - known as zombies - that simultaneously bombarded a target Web site with so many requests for pages that it would be impossible for others to gain access to the site.

And all for the sake of selling a few more sports jerseys.

The facts of the case, as given by law enforcement officials, may seem trivial: a small-time Internet merchant enlisting a fellow teenager, in exchange for some sneakers and a watch, to disable the sites of two rivals in the athletic jersey trade. But the method was far from rare.

Experts say hundreds of thousands of computers each week are being added to the ranks of zombies, infected with software that makes them susceptible to remote deployment for a variety of illicit purposes, from overwhelming a Web site with traffic - a so-called denial-of-service attack - to cracking complicated security codes. In most instances, the user of a zombie computer is never aware that it has been commandeered.

The networks of zombie computers are used for a variety of purposes, from attacking Web sites of companies and government agencies to generating huge batches of spam e-mail. In some cases, experts say, the spam messages are used by fraud artists, known as phishers, to try to trick computer users into giving confidential information, like bank-account passwords and Social Security numbers.

Officials at the F.B.I. and the Justice Department say their inquiries on the zombie networks are exposing serious vulnerabilities in the Internet that could be exploited more widely by saboteurs to bring down Web sites or online messaging systems. One case under investigation, officials say, may involve as many as 300,000 zombie computers.

While the use of zombie computers to launch attacks is not new, such episodes are on the rise, and investigators say they are devoting more resources to such cases. Many investigations remain confidential, they say, because companies are hesitant to acknowledge they have been targets, fearful of undermining their customers' confidence.

In one recent case, a small British online payment processing company, Protx, was shut down after being bombarded in a zombie attack and warned that problems would continue unless a $10,000 payment was made, the company said. It is not known whether the authorities ever arrested anyone in that case.

Zombie attacks have tried to block access to Web sites including those of Microsoft, Al Jazeera and the White House. In October 2002, a huge but ultimately unsuccessful attack was mounted against the domain-name servers that manage Internet traffic. The attackers were never caught.

Federal officials say the case involving the athletic jerseys was solved after some college computers in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania were found to be infected with software code traced to a user whose Internet name was pherk. That hacker, a high school student in New Jersey, told investigators that he was acting at the behest of a merchant - the owner of www.jerseydomain.com.

The merchant, an 18-year-old Michigan college student, could face trial later this year in a federal court in Newark. The case offers a rare glimpse both into the use of zombie computers and into the way that law enforcement officials are trying to combat the problem.

More than 170,000 computers every day are being added to the ranks of zombies, according to Dmitri Alperovitch, a research engineer at CipherTrust, a company based in Georgia that sells products to make e-mail and messaging safer.

"What this points out is that even though critical infrastructure is fairly well secured, the real vulnerability of the Internet are those home users that are individually vulnerable and don't have the knowledge to protect themselves," Mr. Alperovitch said. "They pose a threat to all the rest of us."

Mr. Alperovitch said that CipherTrust had detected a sharp rise in zombie computers in recent months, from a daily average of 143,000 newly commandeered computers in March to 157,000 in April to 172,000 last month.

He said that the increase was attributable to two trends: the rising number of computers in Asia, particularly China, which do not use software to protect against zombies and the worldwide proliferation of high-speed Internet connections.

Aside from the use of tools like CipherTrust's within businesses, experts say consumers can largely make their computers off limits to zombie activity by using up-to-date antivirus and antispam software.

One factor helping those seeking to create zombie networks, known as botnets, is the increasing use of high-speed Internet connections in the home. Aside from being able to handle (and generate) more traffic, such households are more inclined to leave computers running - the computers recruited as zombies need to be on when called by the master.

Eric H. Jaso, an assistant United States attorney in Newark who is prosecuting the New Jersey case, said the zombie cases often wind up damaging more than just the target.

"The effects of these attacks on the Internet itself are far ranging and highly damaging to innocent parties," he said. "The ripple effect is that when one server is attacked, other servers are affected and damaged. Web sites crash. Backup systems become unavailable often to entities like hospitals and banks that are part of the critical infrastructure of the country."

The overall damage in the New Jersey case is estimated by the authorities at $2 million.

That investigation began last July 7, when an online sports-apparel merchant, Gary Chiacco, told federal authorities that traffic to his site, jersey-joe.com, had been disrupted for several days, at a cost of hundreds of thousands of dollars of lost sales. When customers tried to gain access to the site, they would be greeted with an error message.

The attacks continued through the fall of last year and became so severe that they affected service to other customers of the Web-site hosting company used by Jersey Joe.

The host company ultimately told Jersey Joe to go elsewhere, as did two other companies that it then tried to use and that suffered problems from the zombie attacks.

Federal and state investigators say the case was cracked through a combination of luck and sleuthing. While the F.B.I. continued to monitor the attacks on Jersey Joe, student computers at colleges in Massachusetts and Pennsylvania were found to be infected with the software that converted them into zombies.

Hackers "find computers on colleges to be particularly attractive because they have a larger bandwidth and are able to send more packets of data," said Kenneth R. Sharpe, a deputy attorney general in New Jersey involved in prosecuting the case.

A close examination of those computers disclosed the software had been trying to communicate with a user named pherk. Investigators traced the name and an Internet computer address to a 17-year-old high school student from Edison, N.J., named Jasmine Singh.

Confronted by law-enforcement authorities, Mr. Singh acknowledged his involvement and said it was at the behest of an 18-year-old businessman, Jason Arabo, whom he had met through a mutual friend. Mr. Arabo ran a sports jersey business from his home, selling online at www.customleader.com and www.jerseydomain.com.

Investigators determined that Mr. Singh had spread the rogue software through file-sharing networks like Kazaa, using the Jennifer Lopez come-on, and instructed the zombie computers to attack two of Mr. Arabo's competitors - Jersey Joe and another online shirt company, Distant Replays of Atlanta. His compensation, he said, was three pairs of sneakers and a watch.

The F.B.I. then set up a sting operation against Mr. Arabo. According to court papers, an undercover investigator held a series of instant-messaging chats with Mr. Arabo on America Online in December. Mr. Arabo told the undercover agent that he had previously recruited Mr. Singh and that those attacks had not done enough harm to keep his rivals offline, the court papers assert.

According to the court papers, Mr. Arabo asked the agent to mount denial-of-service attacks against rivals in exchange for sports apparel and watches. In later chats that month, he asked the agent to "take down" Jersey Joe's server and redirect its Internet traffic to a pornographic site, the court papers say, and repeatedly asked the agent to "hit them hard."

Mr. Arabo, a student at a community college in a Detroit suburb, was arrested in March and charged in a federal criminal complaint with conspiracy to use malicious programs to damage computers used in interstate commerce. He remains free on $50,000 bail and the condition that he stay off computers and the Internet. (The jerseydomain.com site now carries the notice "Under New Management.") He faces a maximum sentence of five years.

His lawyer, Stacey Biancamano, did not respond to several messages seeking comment.

For his part, Mr. Singh pleaded guilty last month in New Jersey Superior Court to charges of computer theft. Under a plea agreement, he faces a maximum sentence of five years at a youth correction center when he is sentenced in August, but the state prosecutor's office says it will not object to probation.

Mr. Sharpe, the New Jersey prosecutor in the case, said that Mr. Singh had boasted to his high school friends about his ability to create the zombie networks. "It was an ego thing," Mr. Sharpe said. "Hacking in its purest form is not about compensation or about wrecking a Web site. Hacking in its pure form is to show what you can do."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections XML Help Contact Us Work for Us Back to Top

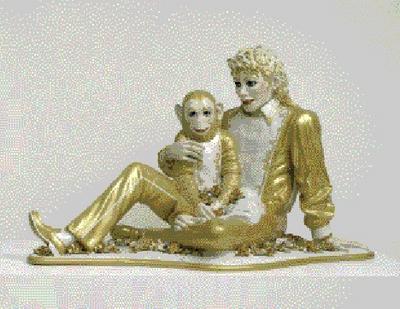

Michael Jackson and Bubbles, 1988, porcelain.

DOUGLAS M. PARKER STUDIO/BROAD ART FOUNDATION, SANTA MONICA/©JEFF KOONS

The Selling of Jeff Koons

He made banality blue chip, pornography avant-garde, and tchotchkes into trophy art. How Jeff Koons, with the support of a small circle of dealers and collectors, masterminded his fame and fortune

By Kelly Devine Thomas

E arlier this year some of the most powerful players in the art world attended a 50th birthday party for Jeff Koons, the controversial art star who rose to fame in the 1980s. Jeffrey Deitch, who helped bankroll Koons’s ambitious and outsize “Celebration” series and nearly went bankrupt for it in the 1990s, hosted the party at his SoHo gallery, where examples from Koons’s oeuvre were projected on large screens and miniature versions of Balloon Dog, an iconic work, were handed out as party favors.

Michael Jackson and Bubbles, 1988, porcelain.

DOUGLAS M. PARKER STUDIO/BROAD ART FOUNDATION, SANTA MONICA/©JEFF KOONS

Among the high-profile museum directors, curators, artists, and collectors in the room that night were Koons’s longtime New York dealer Ileana Sonnabend, with whom he has worked on and off since 1986; Larry Gagosian, who recently began showing Koons’s new works and is now producing his “Celebration” sculptures; Robert Mnuchin, chairman of C&M Arts, which hosted a comprehensive Koons exhibition last May; and dealer William Acquavella.

The deep-pocketed gathering was indicative of the level of support currently invested in Koons, the former Wall Street commodities broker who has polarized opinion in the art world for more than two decades and whose pieces have fetched as much as $5.6 million at auction. Koons disappeared from the art-world radar for much of the 1990s, when he went through a messy divorce and struggled to deliver his “Celebration” series—sculptures and paintings depicting toys and childhood themes blown up to fantastical proportions, such as the ten-foot-tall, stainless-steel Balloon Dog that weighs more than a ton. “He has a vision that goes beyond his collectors,” says Gagosian. “It’s a huge vision, and it’s out there. But he connects the dots in one of the more interesting ways I’ve seen.”

Koons’s auction prices skyrocketed in 1999, when newsprint magnate Peter Brant paid a then record $1.8 million at Christie’s for Pink Panther (1988), a sculpture of the cartoon character hugging a buxom blonde, which was the first of Koons’s major porcelain works to appear at auction. Before 1999 his highest auction price was $288,500. Since the Pink Panther sale, more than 15 works have been auctioned for more than $1 million each. Four years ago Norwegian collector Hans Rasmus Astrup paid a record $5.6 million for Michael Jackson and Bubbles (1988), which was originally priced at $250,000, and last May financier Thomas H. Lee paid $5.5 million for Jim Beam J. B. Turner Train (1986), which was originally priced at $75,000.

How did an artist who sold his works for relatively modest prices two decades ago reach such peaks? Collectors, dealers, curators, and auction specialists who spoke with ARTnews say that Koons has masterminded his fame and fortune through a combination of charm, guile, and a talent for creating expensive art that inspires critical debate. Despite repeated requests, Koons declined to be interviewed for this article. “As Koons likes to point out, someone in every generation has to be held up as a shining example of what is wrong with current art,” Paul Schimmel, chief curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, once observed. “It is a dirty job, but Koons, who has the single-mindedness of a missile, has taken on the duty. Koons’s conceptual strategy is to reveal his ambition.”

Koons has achieved his ambition, sources say, with the help of a close circle of dealers, including Sonnabend, Deitch, Gagosian, and, more recently, Mnuchin, as well as a core group of collectors, among them, Brant, Los Angeles real estate developer Eli Broad, Greek construction tycoon Dakis Joannou, Chicago collector Stephan Edlis, and Christie’s owner François Pinault, who have made him a cornerstone of their collections and continue to acquire many of the new works that come out of his studio.

Over the years, Koons has persuaded patrons to pay for the fabrication of his sculptures, which can run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. He has limited supply by placing these works with important private and public collections from which they are unlikely to be sold; and he has created artworks whose seductive surfaces, expensive scale and quality, and flawless execution cast them as luxury consumer objects. “He is a trophy artist,” says Chicago dealer Donald Young, who worked with Koons on his 1988 “Banality” series. “And he isn’t against being a trophy artist.”

While artists typically separate art and money, Koons’s art addresses market forces head on. Says art historian Robert Pincus-Witten, director of exhibitions at C&M Arts, “Jeff recognizes that works of art in a capitalist culture inevitably are reduced to the condition of commodity. What Jeff did was say, ‘Let’s short-circuit the process. Let’s begin with the commodity.’”

As Dan Cameron, chief curator at New York’s New Museum of Contemporary Art, notes, “If all you want is a good time, he won’t let you down. But underneath the primitive thirst for delight and pleasure in his works, I think he is deeply engaged in some philosophical questions. Both Marxists and kids can enjoy it.”