Friday, June 24, 2005

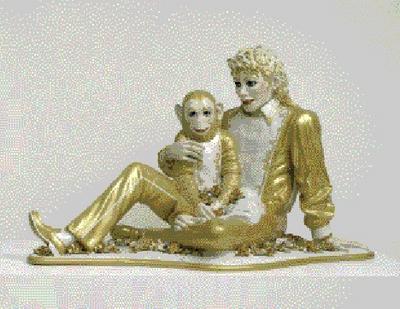

Michael Jackson and Bubbles, 1988, porcelain.

DOUGLAS M. PARKER STUDIO/BROAD ART FOUNDATION, SANTA MONICA/©JEFF KOONS

The Selling of Jeff Koons

He made banality blue chip, pornography avant-garde, and tchotchkes into trophy art. How Jeff Koons, with the support of a small circle of dealers and collectors, masterminded his fame and fortune

By Kelly Devine Thomas

E arlier this year some of the most powerful players in the art world attended a 50th birthday party for Jeff Koons, the controversial art star who rose to fame in the 1980s. Jeffrey Deitch, who helped bankroll Koons’s ambitious and outsize “Celebration” series and nearly went bankrupt for it in the 1990s, hosted the party at his SoHo gallery, where examples from Koons’s oeuvre were projected on large screens and miniature versions of Balloon Dog, an iconic work, were handed out as party favors.

Michael Jackson and Bubbles, 1988, porcelain.

DOUGLAS M. PARKER STUDIO/BROAD ART FOUNDATION, SANTA MONICA/©JEFF KOONS

Among the high-profile museum directors, curators, artists, and collectors in the room that night were Koons’s longtime New York dealer Ileana Sonnabend, with whom he has worked on and off since 1986; Larry Gagosian, who recently began showing Koons’s new works and is now producing his “Celebration” sculptures; Robert Mnuchin, chairman of C&M Arts, which hosted a comprehensive Koons exhibition last May; and dealer William Acquavella.

The deep-pocketed gathering was indicative of the level of support currently invested in Koons, the former Wall Street commodities broker who has polarized opinion in the art world for more than two decades and whose pieces have fetched as much as $5.6 million at auction. Koons disappeared from the art-world radar for much of the 1990s, when he went through a messy divorce and struggled to deliver his “Celebration” series—sculptures and paintings depicting toys and childhood themes blown up to fantastical proportions, such as the ten-foot-tall, stainless-steel Balloon Dog that weighs more than a ton. “He has a vision that goes beyond his collectors,” says Gagosian. “It’s a huge vision, and it’s out there. But he connects the dots in one of the more interesting ways I’ve seen.”

Koons’s auction prices skyrocketed in 1999, when newsprint magnate Peter Brant paid a then record $1.8 million at Christie’s for Pink Panther (1988), a sculpture of the cartoon character hugging a buxom blonde, which was the first of Koons’s major porcelain works to appear at auction. Before 1999 his highest auction price was $288,500. Since the Pink Panther sale, more than 15 works have been auctioned for more than $1 million each. Four years ago Norwegian collector Hans Rasmus Astrup paid a record $5.6 million for Michael Jackson and Bubbles (1988), which was originally priced at $250,000, and last May financier Thomas H. Lee paid $5.5 million for Jim Beam J. B. Turner Train (1986), which was originally priced at $75,000.

How did an artist who sold his works for relatively modest prices two decades ago reach such peaks? Collectors, dealers, curators, and auction specialists who spoke with ARTnews say that Koons has masterminded his fame and fortune through a combination of charm, guile, and a talent for creating expensive art that inspires critical debate. Despite repeated requests, Koons declined to be interviewed for this article. “As Koons likes to point out, someone in every generation has to be held up as a shining example of what is wrong with current art,” Paul Schimmel, chief curator of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, once observed. “It is a dirty job, but Koons, who has the single-mindedness of a missile, has taken on the duty. Koons’s conceptual strategy is to reveal his ambition.”

Koons has achieved his ambition, sources say, with the help of a close circle of dealers, including Sonnabend, Deitch, Gagosian, and, more recently, Mnuchin, as well as a core group of collectors, among them, Brant, Los Angeles real estate developer Eli Broad, Greek construction tycoon Dakis Joannou, Chicago collector Stephan Edlis, and Christie’s owner François Pinault, who have made him a cornerstone of their collections and continue to acquire many of the new works that come out of his studio.

Over the years, Koons has persuaded patrons to pay for the fabrication of his sculptures, which can run into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. He has limited supply by placing these works with important private and public collections from which they are unlikely to be sold; and he has created artworks whose seductive surfaces, expensive scale and quality, and flawless execution cast them as luxury consumer objects. “He is a trophy artist,” says Chicago dealer Donald Young, who worked with Koons on his 1988 “Banality” series. “And he isn’t against being a trophy artist.”

While artists typically separate art and money, Koons’s art addresses market forces head on. Says art historian Robert Pincus-Witten, director of exhibitions at C&M Arts, “Jeff recognizes that works of art in a capitalist culture inevitably are reduced to the condition of commodity. What Jeff did was say, ‘Let’s short-circuit the process. Let’s begin with the commodity.’”

As Dan Cameron, chief curator at New York’s New Museum of Contemporary Art, notes, “If all you want is a good time, he won’t let you down. But underneath the primitive thirst for delight and pleasure in his works, I think he is deeply engaged in some philosophical questions. Both Marxists and kids can enjoy it.”

Critical response to Koons’s encased vacuum cleaners, floating basketballs, gilded celebrities, and stainless-steel and porcelain tchotchkes has been extreme. Even his fans have had trouble reconciling their love-hate relationship with him. Peter Schjeldahl, now an art critic for the New Yorker, once proclaimed, “Jeff Koons makes me sick. He may be the definitive artist of this moment, and that makes me the sickest. I’m interested in my response, which includes excitement and helpless pleasure along with alienation and disgust . . . I love it, and pardon me while I throw up.”

Koons, who was born in 1955 in York, Pennsylvania and lives today in a 13-room town house on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, came of age as an artist during a decade when contemporaries like Julian Schnabel were aggressively promoting themselves, eager to expand their markets to the level of music and movie legends. Koons’s breakthrough exhibition took place in 1985 at International with Monument, in the East Village, when the neighborhood was the haunt of collectors like British advertising mogul Charles Saatchi on the hunt for young talent.

Koons moved to New York when he was 22 and got a job selling memberships at the Museum of Modern Art. His earliest supporter was dealer Mary Boone, who met him in 1979 when she bought his green Mercedes as a birthday gift for Schnabel. Boone sold two of his works—to Saatchi and collectors Donald and Mera Rubell—but after a year Koons left her for dealer Annina Nosei, with whom his relationship was also short-lived.

Koons’s work, with its roots in Pop, Conceptual, and Minimalist art, was out of step with the brash Neo-Expressionist style of artists like Schnabel and David Salle, which was in favor at the time. Frustrated by a lack of sales, Koons moved to Florida in the summer of 1982 to live with his parents and save enough money to move back to New York in the fall.

For the next few years, he personally financed his art by working as a Wall Street commodities broker. Koons has said he spent a lot of his time at Smith Barney consumed with a new series of sculptures, calling physicists to help him figure out how to suspend basketballs in water.

“Equilibrium,” his groundbreaking 1985 show at International with Monument, included basketballs floating in aquariums, lifesaving devices cast in bronze, and reproductions of Nike advertisements featuring black basketball stars. The basketball tanks, in editions of two, originally sold for $3,000, and the lifeboats, in an edition of three plus one artist’s proof, sold for $8,000, but those prices doubled within a matter of months. In recent years a lifeboat and an aqualung have sold for about $2 million each at auction. Less in demand are the basketball tanks, whose top price at auction is $244,500, because, sources say, they are difficult to maintain and the balls deteriorate.

“With Jeff Koons, I was absolutely obsessed,” says art adviser Estelle Schwartz, who placed about a dozen works from “Equilibrium” with clients. “I was a more voracious collector than even my clients. I remember saying to a collector, ‘If I’m buying a snorkel vest, you should be buying an aqualung.’”

“Equilibrium” set off a whirlwind of exhibitions by Koons. Between 1985 and 1991, he showed five distinct but often overlapping series of works at galleries across the country and overseas. He also began to work with multiple dealers, including Daniel Weinberg of Los Angeles, who, like other dealers who have worked with Koons, helped the artist fund his ideas in exchange for a share of the profits.

Over the past two decades, Koons, who has been quoted as saying that the “great artists of the future are going to be the great negotiators,” has built what he describes as a power base. “I have a platform now,” he told an interviewer in 1990. “I have all the support possible, as far as a stage for Jeff Koons to do his work.”

In addition to an increasing number of dealers who compete to handle his new works and buy those that appear at auction, Koons convinced collectors Joannou, Brant, and Broad, along with dealers Deitch, London’s Anthony d’Offay, and Cologne’s Max Hetzler, to invest heavily in the fabrication of the “Celebration” series. Koons began the series after his ex-wife Ilona Staller, a Hungarian-born porn star in Italy, and the inspiration for Koons’s sexually explicit 1991 “Made in Heaven” series, left him in 1993 and took their son to Italy, sparking a long-running custody fight.

Koons has always acted as the head of a complicated operation that requires the cooperation and support of many people, but never before on the scale required by “Celebration,” which Koons has said was an attempt to communicate with his estranged son. Deitch, Hetzler, and d’Offay funded the project in part by selling works to collectors before they were fabricated. But the sculptures, which were sold for between $1 million and $2 million in the late 1990s, proved more difficult and expensive to fabricate than anticipated.

Eli Broad paid for Balloon Dog (1994–2001) and Cat on a Clothesline (1994–2001) in 1996, but he didn’t receive them until 2001. “Jeff won’t let go of a work until he thinks it’s perfect,” Broad says. The delays tested his patience and required more money from Broad, who declined to specify what he paid for them. He says he didn’t threaten to take legal action against Deitch, Hetzler, and d’Offay but did make his expectations clear. “These were three responsible dealers, and we had a contract where they had to perform.”

At one point, more than 75 artists were working for Koons around the clock as he tried to finish the project in time for a “Celebration” exhibition at the Guggenheim, originally scheduled for 1996 but repeatedly postponed and ultimately canceled. “It was a pure panic situation,” says an artist who worked for Koons at the time. “I would get a call from a manager saying that they’d run out of money and were going to have to shut down the studio for a week or so.”

In the mid-1990s, Koons sold most of his artist’s proofs to Broad and others to help finance his work and pay his bills. Broad bought three: Rabbit, Michael Jackson and Bubbles, and St. John the Baptist (1988). Says Sonnabend director Antonio Homem, “Jeff is an extremely romantic artist. He is ready to ruin himself and anyone involved with him for an artwork to be what he wants it to be. He wants it to be beyond perfection. He wants it to be a miracle.”

In an extreme example of his attention to detail, Koons insisted about two years ago that Broad’s Balloon Dog, which had been exhibited at several major museums, be repainted a different shade of blue, at Koons’s expense.

Koons did not exhibit a new series of work for much of the 1990s, when the slow production of “Celebration,” caused what Brett Gorvy, Christie’s international cohead for postwar and contemporary art, describes as a “cloud of confusion to hang over his market.” He reappeared on the art scene with a new series of cartoonish mirrors and surrealistic paintings called “EasyFun” at Sonnabend in 1999, the same year that two of his major works appeared at auction.

When the nearly life-size Buster Keaton (1988) was offered at Christie’s in May 1999, it ignited a bidding duel between d’Offay, who bought the work for $409,500, and Philippe Ségalot, head of Christie’s contemporary-art department at the time, who was bidding on behalf of an anonymous client. The competition for Pink Panther was even more intense six months later, when it doubled its estimate of $600,000 to $800,000.

Exhibitions of Koons’s works in the past five years have often coincided with the appearance of high-profile works at auction. Most of the art in the C&M Arts show last May—the same month as Christie’s well-publicized sale of Jim Beam J. B. Turner Train—was on loan from Brant, Edlis, Sonnabend, and other public and private lenders. Few of the works were for sale, but the exhibition set new price levels for those that were available. Mnuchin, according to sources, sold Wall Relief with Bird (1991) for about $2 million, three times the price it sold for at Sotheby’s five years ago.

A 1993 retrospective at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art was Koons’s last major museum exhibition in the United States, despite the Guggenheim’s desire to present a retrospective of his works. “The question of a retrospective is still ongoing,” says Guggenheim deputy director and chief curator Lisa Dennison. “Determining the point when you want a retrospective that sums up your career is a tough one for any artist. I think it’s particularly tough for Jeff.” Sources say that Pinault—who has been approached about financing a new sculpture of an intermittently chugging train engine suspended by a 150-foot crane—plans to open his art foundation in Paris in about three years with a major Koons exhibition.

A much-delayed exhibition of the “Celebration” sculptures, most of which went directly into private hands and have never been shown as a group, is at least 18 months away, says Gagosian, who is still financing the production of some of the works and selling them for $2 million to $6 million.

While critics over the past 20 years have faulted Koons for debasing art with consumer fetishism, his supporters say they believe he is one of the most important artists of his generation.

“I think it was hard in the 1980s to take seriously a man who was saying that banality is the white elephant of our culture,” says the New Museum’s Dan Cameron. “But I think in 2005 we’re moving closer to Jeff. I think we’ll look back and say that he had it right on the money.”

Kelly Devine Thomas is senior writer of ARTnews.

This article has been edited for the ARTnews Web site.