Monday, February 07, 2005

Tuesday, February 08, 2005

FINDING ONE'S WAY Some directives for surviving Washington are not so obvious.

WASHINGTON THE start of every presidential term brings to Washington eager new cabinet officers and members of Congress who take the wrong elevators, get lost in the hallways and pop off to reporters. But such faux pas - Senator Ken Salazar, a freshman Democrat from Colorado, says he has not yet found the Senate dining room and is eating ham sandwiches in the public cafeteria - are hardly the worst of it. As everyone knows, Washington is shadowed by the specters of grand scandals past: Richard M. Nixon and Watergate, Oliver North and Iran-Contra, Bill Clinton and Monica Lewinsky. More recently Bernard B. Kerik, President Bush's short-lived nominee for homeland security secretary, jettisoned himself for his troubles with a nanny and then turned out to have a Manhattan love nest, a serious no-no in Washington. Unlike New York, the nation's capital has always had a Puritan streak and remains a curious mix of raging ambition and Midwestern values. So now that the president's State of the Union address has signaled the official start of the year, here are 10 rules, culled from those who have learned the hard way, for avoiding social, political and legal disaster in Washington. 1. Don't get up in the middle of dinner and announce that you have to run off to do "Larry King Live." Well-mannered Washingtonians tell hostesses that they will drop by before or after their appearances on nightly programs like Mr. King's. "You should tell your hostess ahead of time," said Sally Quinn, the Washington writer and hostess who is married to Benjamin C. Bradlee, former executive editor of The Washington Post, and the author of a book on entertaining. Otherwise, Ms. Quinn said, there will be a gaping hole at the dinner table. (Mr. King's interview show is on CNN at 9 p.m.) For dinner on big occasions like election night, guests can graze in the shows' green rooms, the lavishly catered holding areas that have evolved into the new Washington dinner parties. 2. Don't use the expression "Do you know who I am?" The answer from the young woman looking for your lost ticket at the charity dinner check-in table may well be an embarrassing no. Also, the question is generally not effective, unless your goal is frightening her. "It doesn't make your ticket appear more quickly," said Carolyn Peachey, a longtime Washington event planner who has heard the expression for decades. The only time Ms. Peachey has given a dispensation for the expression's use was last fall, when the music mogul Quincy Jones was prevented from entering a reception at the State Department. A plate in his head from brain surgery had set off the metal detector, Ms. Peachey said, and 20 minutes of talking to the guards made no difference. "Do you know who I am?" Mr. Jones finally asked. The guard replied yes, Ms. Peachey said, but insisted there was nothing to be done. Mr. Jones eventually got in through intervention from higher-ups. 3. Don't withhold information from your lawyer. Former White House counsels, lawyers for white-collar criminals, and the city's highly paid damage controllers all agree: This is the premier mistake that otherwise intelligent people make in Washington. Cover-ups are often worse than the problems themselves. "What inevitably happens is that the facts dribble out, compounding the story, because reporters are not going to give up until they beat the competition and dig up something new," said Lanny J. Davis, a Washington lawyer brought in for White House damage control during the Clinton scandals and the author of "Truth to Tell: Tell it Early, Tell it All, Tell it Yourself." Fred F. Fielding, the White House counsel for Ronald Reagan, who vetted the current President Bush's cabinet nominees during the 2000 transition, heartily agrees. Nominees have to be prepared, he said, honestly to answer the awful questions posed by White House lawyers: Have you ever had an affair? Or used drugs? A yes to either of those questions, Mr. Fielding added, was not necessarily a problem. "There's a difference between somebody having an affair years ago, before their first marriage broke up, and someone having an affair with someone he supervised," he said. As for drugs, "occasional drug use in college would not be a disqualifier." 4. Don't change your hairstyle too often. "There is zero tolerance for coif inconsistency," said Mary Matalin, a longtime adviser to Vice President Dick Cheney and a former television talk show host who is, at the moment, a brunette. Over the years she has been blonde, light brown or, as she put it, "hijacked by hyper-highlights ranging from dull orange to bright white." In short, Ms. Matalin said, "You have to pick a color and stick with a color." 5. Don't plan to announce your new nominee before a proper vetting. This applies more to presidents than to ordinary folk, but it is an important corollary of Rule No. 3. C. Boyden Gray, the White House counsel for the first President Bush, said that he was under constant pressure from the president and his staff rapidly to investigate the background of cabinet nominees so that Mr. Bush could fill jobs. "I was pounded, relentlessly, when I was counsel," Mr. Gray said. He recalled that in 1988, when President-elect Bush insisted on quickly announcing Carla A. Hills as the United States trade representative, Ms. Hills and Mr. Gray agreed that Ms. Hills's husband, Rod, would have to resign from a steel company board to avoid any conflict of interest with his wife's new job. The problem was that Mr. Hills was on a plane until 4 p.m., and the president wanted Ms. Hills announced at 2 p.m. But she refused to say publicly that her husband would resign from the steel board without asking him first. So Mr. Gray called the Federal Aviation Administration and got in touch with the commercial plane's pilot, who summoned Mr. Hills to the cockpit, where Mr. Hills gave his O.K. "I think it violated all kinds of F.A.A. rules," Mr. Gray said. "The point of the story is that these are very difficult issues, and you can't back down." 6. Don't wear a beaded Armani to a Friday night dinner in Cleveland Park. The clean lines of Armani are highly desirable in Washington, and the first lady's white cashmere Oscar de la Renta wowed the town on Inaugural day. But even in a city as formal as the capital, be careful not to overdress. Andrea Mitchell, the NBC correspondent who is married to Alan Greenspan, the chairman of the Federal Reserve Board, said she was reminded of that recently when she wore a black silk Armani pantsuit with a beaded top to dinner one Friday in Cleveland Park, an affluent, liberal enclave of faded Volvos in the city's northwest quadrant. Every other woman, she said, was in slacks and turtlenecks. What to do? "Laugh it off and realize that in Washington what you say and what you know is more important than what you wear," Ms. Mitchell said. 7. Don't think it is your job to educate reporters. "You just bite your tongue on certain topics," said Ed Rollins, a veteran Republican strategist and the manager of Christie Whitman's successful campaign for governor of New Jersey in 1993. Mr. Rollins did not follow his own advice later that year, when he infamously boasted to reporters at a breakfast in Washington that Ms. Whitman's campaign had paid African-American ministers and Democratic workers $500,000 in "walking-around money" to suppress the black vote. This statement, immediately recanted, prompted a federal investigation, which found nothing illegal. But Mr. Rollins's words had brought the political establishment down on his head and tainted Ms. Whitman's victory. 8. Don't believe your own spin. "I was guilty of that," said Mr. Davis, the Clinton defender. Mr. Davis said he first spun out the argument that there was nothing wrong with political donors attending coffees at the Clinton White House because no money was actually collected there. "I tried to believe it, because I was technically correct," Mr. Davis said. "But people were expected to give money before or after the event." 9. Don't forget who your friends are. "The biggest mistake that people make is that they base their friendships on who is in power and who is not," Ms. Quinn said. "This is short-sighted, because very few people in Washington stay in power for a length of time. In the same vein, people will count people out once they lose power. This is always a huge mistake, because people are never out unless they're in the ground with a stake in the heart." 10. Don't forget where you came from, and that integrity matters. "People think the values here will be different than the ones they left at home, and they're not," said Robert S. Strauss, a Washington sage who is the former chairman of the Democratic National Committee and a longtime Bush family friend. "It's the same damn thing that you have in Dallas or Los Angeles or Houston. People value loyalty here as much or more as they do anywhere else." If all else fails, Mr. Fielding has the surefire way to avoid social, political and legal ruin in Washington. "Move to Kansas," he said. Copyright 2005

February 8, 2005

Holding On to Dynasty Is Patriots' Next Challenge

By DAMON HACK

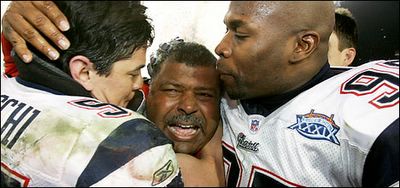

JACKSONVILLE, Fla., Feb. 7 - In the frantic final days before Super Bowl XXXIX, with schemes to study and history to clutch, the New England Patriots dispatched members of their personnel department to begin scrutinizing salary-cap numbers and college rosters for the draft in April.

Those are some of the behind-the-scenes maneuvers that have elevated the Patriots above the gravitational pull of parity. By preparing for every possibility - be it a coaching departure or the loss of a player - Coach Bill Belichick has rarely been caught unprepared.

"A lot of coaches in the N.F.L. work hard," Jimmy Johnson, the former coach of the Dallas Cowboys and the Miami Dolphins, said in praising Belichick last week. "But there is a difference between working hard and working smart."

The Patriots stamped themselves as a dynasty Sunday with their 24-21 victory over the Philadelphia Eagles at Alltel Stadium for their third Super Bowl title in four seasons. But New England's bid to claim a fourth Super Bowl crown next season - and a third straight, which would be a first - will face its most challenging test since the run began.

Romeo Crennel, the Patriots' defensive coordinator since 2001, has accepted the Cleveland Browns' coaching job. Charlie Weis is expected to report Thursday to South Bend, Ind., leaving the Patriots' offensive coordinator post for the Irish coaching job he accepted in December.

Although most of New England's starters will return, the Patriots could enter the free-agent period with some key unsigned players, including receiver David Givens, guard Joe Andruzzi and place-kicker Adam Vinatieri, whose contracts expire March 1.

The Patriots must also decide whether to keep the injured cornerback Ty Law, who is set to count roughly $12 million against the 2005 salary cap.

On Monday, just hours after he thanked Weis and Crennel for their contributions to New England, Belichick said of the vacancies, "We'll deal with that in due course."

The Patriots are probably dealing with it already.

Belichick refused to name candidates, but he has assistants with strong ties to the team. For the defensive coordinator job, the 34-year-old secondary coach, Eric Mangini, is thought to be the lead candidate. Mangini, like Belichick, is a graduate of Wesleyan in Middletown, Conn. He was later an assistant under Belichick in Cleveland in 1995 and worked under Bill Parcells and Belichick with the Jets from 1997 to 1999 before moving to New England with Belichick in 2000.

But he is also a rising star on the radar of several teams.

One potential replacement for Weis is Dante Scarnecchia, Belichick's assistant head coach and offensive line coach.

Scarnecchia, who will turn 57 on Feb. 15, has been a Patriots assistant for 21 seasons. In 35 years coaching in college and the N.F.L., Scarnecchia has also taught tight ends, special teams, linebackers and defensive backs. With a surprisingly low profile given his longevity and success, he has coached three different right tackles in three Super Bowls.

The tight ends coach Jeff Davidson and the running backs coach Ivan Fears have also been talked about as replacements for Weis.

How crucial is losing Crennel and Weis?

"They are two outstanding coaches, but the thing is, they have Belichick," the Eagles' defensive coordinator, Jim Johnson, said last week. "That's the key. They still have the head man, and I'm sure Bill has a plan. He probably already has someone else in mind."

Different forces have brought down the league's dynasties through the years, including age and the defection of talented assistants. New England must cope with both.

The Pittsburgh Steelers - who won four titles in six years through the 1979 season - and the San Francisco 49ers - who won five titles between the 1981 and 1994 seasons - remained strong until their Hall of Fame talent base, among other things, eroded.

The Dallas Cowboys, the only team besides the Patriots to win three titles in four seasons, sustained significant free-agent losses toward the end of their championship run in the 1995 season, one year after the start of the salary-cap era.

"The difference now is that you don't see other dynasties functioning at the same time," Bill Walsh, who won three titles with San Francisco, said in a telephone interview Monday. "When we were at our best, so were the Giants and Redskins and many other teams in the N.F.C. and A.F.C. We had to deal with other dynasties that were dominant. I don't think you see the caliber of teams now that you saw then because of free agency, but New England is an outstanding team, and their accomplishment is magnificent."

Walsh, who cited the quarterback position as the key to sustained success, said different factors could crack the foundation of a dynasty.

"Sometimes it's the combination of the players changing," he said. "Some age and don't perform as well. A loss of focus can occur. Coaching staffs change because men become head coaches out of the staff. We lost a series of guys that we had to replace, and I'm sure the Patriots will, too."

Only New England has won three titles in the cap era, which was intended to spur competition, not create dynasties. Commissioner Paul Tagliabue, however, said the cap was not designed to be so rigid that a team could not enjoy years of prosperity.

"When we did this system in the early 90's, we thought there was enough flexibility in it so you could keep teams together and have repeat success," Tagliabue said. "New England's done it, Philadelphia's done it, the Rams did it, the Broncos did it. Other teams have done it. Green Bay has had a phenomenal era and a phenomenal quarterback through the salary-cap years. And I think that's one of the lessons.

"We thought the system would allow for great competition and allow for repeat winners, and that's what's turning out to be the case."

New England is in an ideal position to remain atop the league.

Quarterback Tom Brady is signed through 2006, linebacker Tedy Bruschi through 2007 and safety Rodney Harrison through 2008. Though linebackers Roman Phifer and Ted Johnson may retire, the Patriots should attract A-list free agents.

"It takes a lot of discipline," Scott Pioli, the Patriots' vice president for player personnel, said of playing for New England. "It's not about how long their hair is or how much jewelry they wear. We have certain expectations for guys being in the right place at the right time and doing their job a certain way. That's discipline to us."

Belichick was still not ready to judge his team's place in history. The 2005 season beckons.

"We'll start at the bottom of the heap like everybody else," he said.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company

BRENT STEVENS did not sleep on that February weekend in 1990. A newly minted Wharton School M.B.A., Mr. Stevens had recently joined Drexel Burnham Lambert, the swashbuckling investment bank that dominated the market for financing risky companies. That Sunday, after working on a deal nonstop for 48 hours, he received an ominous telephone call from a managing director, telling him to go home. He was dumbfounded. Deals were over when they were over, he said, and no one at Drexel slept until they were. The next morning, Mr. Stevens arrived at 5:30 at Drexel's office in Beverly Hills to find his boss, Robert Beyer, sitting in his chair. "You're going to hear some pretty difficult things today," he recalled Mr. Beyer telling him. "A lot of them will be true. Don't worry, you'll be fine." Within the hour, Mr. Stevens learned that Drexel, once the most profitable and feared bank on Wall Street, had a liquidity crisis. By evening, the firm would be bankrupt. Later called the "St. Valentine's Day massacre," the bankruptcy left more than 5,700 people in Beverly Hills and New York unemployed and potentially tainted by their association with an institution considered by many people at the time to be defiant, greedy and criminal. That perception, of course, did not come out of thin air. In December 1988, Drexel agreed to plead guilty to six felony counts and to pay a $650 million fine. Three months later, Michael R. Milken, the firm's legendary junk-bond trader, was indicted on 98 charges, including racketeering. He later pleaded guilty to six felony counts, paid $600 million in fines and restitution and served two years in prison. But what became of Mr. Stevens and his co-workers? Today, almost exactly 15 years after the firm's demise, he and many other young employees swept up in the Drexel diaspora have risen to prominent positions on Wall Street. Mr. Stevens is the head of leveraged finance at the Jefferies Group , an investment bank known for lining up complex financing for high-risk companies. Not coincidentally, his boss - Richard B. Handler, the chief executive of Jefferies - was a 28-year-old trader at Drexel when the firm blew up. Several other former Drexel employees are managing billions for pension funds, endowments, wealthy people and one another - often using junk bonds. Mark L. Attanasio, a senior vice president at Drexel when it collapsed, is a managing partner at Trust Company of the West, a $109.7 billion money management firm. Last month, he bought the Milwaukee Brewers for more than $220 million. Interviews with more than two dozen former employees showed that, far from being embarrassed by their connection to Drexel, most retain an almost cultlike devotion to the firm and much of what it stood for. Few of them were crucial players in building Drexel's core franchise, junk bonds. And few of them were especially close to Mr. Milken, who has since survived cancer, established two major foundations devoted to cancer research and become a major investor in an education initiative, Knowledge Universe Inc. But to a person, they all described their Drexel DNA as a crucial factor in their success today. "It showed you the sky was the limit," Mr. Handler said. "You realized you could make a difference in finance. The sheer volume of deals, the market share you could have, your ability to add value to clients, how you could drive your competition nuts, also how much wealth creation was possible." A HANDFUL of Drexel's most senior managers also went on to make names for themselves. Perhaps the best known is former Drexel trader Gary Winnick, who founded Global Crossing, the onetime telecom giant that imploded under a mountain of debt in January 2002. Mr. Winnick cashed in more than $700 million in stock before the firm went belly up. Another veteran star is Leon D. Black, founder of Apollo Management, one of the most respected names in the buyout world. He made his fortune buying the bankrupt portfolio of Executive Life, the insurer. Apollo now manages more than $13 billion, registering compound annual returns of more than 40 percent since 1990 on the $12 billion it has invested. But it is only recently that the younger members of the firm - associates and executive vice presidents, vice presidents and young managing directors - have made their mark. They include Peter J. Nolan, Jonathan D. Sokoloff and John G. Danhakl - all 20-something associates when the firm went bust - who now run Leonard Green & Partners, a private equity shop in Los Angeles that manages $3.7 billion and has posted stellar returns, almost 40 percent a year over the past 16 years. Another is Ken Moelis, who had more seniority at Drexel - though still in his 20's when the firm collapsed - and now is joint global head of investment banking at UBS. The list goes on. The money being made in the credit markets by former Drexel employees is vindication to some former managers, who said they felt that the firm was destroyed unnecessarily. "One prosecutor said to me in 1990, 'With compensation levels like this, this has to be a den of thieves. You couldn't make this much money,' " recalled a former manager who asked not to be identified. "I said, 'Compensation levels are lower than what they will be doing 10 years from now.' " He was right, of course: he and his fellow alumni are making more money today than they ever dreamed during their Drexel days. Mr. Handler's stock and options in Jefferies alone are worth almost $200 million, and Jefferies is one of the best-performing financial stocks on the New York Stock Exchange. The Leonard Green group has returned more than $1.4 billion to investors over the past two years, with each of the three managing partners taking home somewhere in the range of $100 million each. One former government official who was involved in the Drexel case said he was not surprised that many of the alumni had prospered. "The sad thing about Drexel was that a lot of their business was untainted by this, but when it blew up it all blew up," said Gary Lynch, now the general counsel at Credit Suisse First Boston. The legacy of Drexel, gray to the outside world, is as white as snow to the group: It was an institution where hard work and good ideas were rewarded, hierarchies were absent, talent abounded and the potential to be very, very, rich was palatable, former employees said. They recall exactly where they were the morning the firm went bankrupt - as well as the details from the steamy party later that week at the Sugar Shack, a Los Angeles bar, now defunct, where mai tais flowed generously and sex was rampant, several employees recalled. Some still remember their Drexel seniority rank precisely and offer that information voluntarily: 15th to be hired in corporate finance in New York, said one; 10th in trading in Beverly Hills, said another. Almost everyone in the group owns some Drexel memorabilia: a chair, a desk, a computer, all bought or taken during the bankruptcy. And while many were reluctant to be interviewed for this article, once seated, they could not stop talking. To be sure, nostalgia about Drexel's rise and fall is not universal, especially among senior managers. One senior trader who worked with Mr. Milken on his famous X-shaped trading desk and asked not to be identified said: "There were those who sat on the X and those who didn't. There were those who were hired by Mike and those who were not." As for the fond memories of others, he said: "They did not appear before a grand jury. They did not lose millions in stock." No matter what they think of Drexel, however, former employees and other Wall Street watchers seem to agree on this much: there may never be another firm quite like it. "Drexel had a certain chutzpah that hasn't been seen since," said Charles R. Geisst, a Wall Street historian at Manhattan College. "People seem to forget it was the only major financial firm to be shut down by regulators. That's a strong message that chutzpah shouldn't continue." And by most accounts, it hasn't. By the mid-1980's, Drexel was the nexus of the nation's high-yield bond boom and takeover frenzy. Corporate raiders and entrepreneurs like T. Boone Pickens and Ted Turner and Ronald O. Perelman were making plays for companies far bigger than their own. They financed these takeovers with junk bonds, for which Mr. Milken had created a market. The firm - many would say Mr. Milken alone - helped build the cellular, video game and cable industries, including companies like CNN, MCI and McCaw Communications. In 1980, Drexel underwrote 48 high-yield deals that brought in $1.6 billion. In 1989, the firm did 100 deals worth $23.2 billion. Drexel's share of the junk bond market was 40 to 60 percent throughout the decade, according to Thomson Financial. It was not until 1987 that a rival, Credit Suisse First Boston, posted a market share in the double digits. Not surprisingly, Drexel attracted top Ivy League talent. "It was the hot place to go, especially the Beverly Hills office," said Mark Lanigan, who graduated from Harvard Business School in 1986 and now runs an investment fund seeded by another hedge fund group run by former Drexel employees. "They were shaking up the world. Every other day you opened The Wall Street Journal and Drexel was helping to launch a hostile takeover or helping an established company defend itself." Most of the junior bankers chose Drexel over other top-flight banks. They picked it because they thought they could learn more, advance faster, make more money and - corny as it sounds, even on Wall Street - become part of history. "Drexel was tied to a rocket," said Leon Wagner, chairman of GoldenTree Asset Management, a $6.5 billion money management firm, who joined Drexel's high-yield trading desk in 1986 from Lehman Brothers . "Just to be able to sit on the desk and see the calls start at 4:15 in the morning, Boesky and Perelman and Diller and Murdoch," he said referring to Ivan Boesky, the arbitrageur; Mr. Perelman, of Revlon ; Barry Diller, now chairman of IAC/InterActiveCorp, and Rupert Murdoch of the News Corporation . Because the firm controlled the market, young associates were thrown on big deals and told to execute them. "I learned more in five years than I have in the subsequent 15," was a typical observation among the former Drexel employees interviewed. Mr. Attanasio, who made his fortune selling his fund, Crescent Capital, to Trust Company of the West, said, "We were the market, so you learned the market." Frederick H. Joseph, Drexel's former chief executive, who is now managing director and co-head of investment banking at Morgan Joseph & Company, the boutique investment bank, likened the experience to being at a top-notch university. "Harvard is as good as it is because of the people there," he said in an interview. "It's a favorable vicious cycle." There was the money, too - lots of it. The parking lots at the Beverly Hills office were filled with red and yellow Porsches, Ferraris and BMW's. And Drexel knew how to have a party. At the firm's famous Predators' Ball, where it entertained corporate titans, members of the younger generation said they ran around taking notes, gawking at the crowd. Frank Sinatra performed in 1984, Diana Ross in 1985. Star power at credit conferences was rare at the time; the employees thought it was cool. Despite the controversy engulfing the firm in 1990, few employees saw the end coming. Mr. Moelis was skiing with clients in Colorado. Mr. Wagner found out on the Friday before the implosion from his wife. Mr. Attanasio had been in Germany the previous week doing due diligence on a deal. It was by no means immediately apparent that Drexel's young associates and vice presidents were employable. "You had been in Chernobyl," Mr. Nolan said. Many of them kept working on Drexel business: Chris Kanoff, now head of corporate finance at Jefferies, promised to finish a deal for a client and, using the law offices of Latham & Watkins, finished it in eight weeks. Others scrambled to find jobs elsewhere after the bankruptcy. One group went to Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette. Another went to Jefferies, and a third started Canyon Capital Advisors, now a successful $7 billion hedge fund. Mr. Sokoloff joined Leonard Green, and two others would do so later. Some regrouped back East, including Ted Virtue, now the chief executive of MidOcean Partners, a $3 billion private equity fund, and Mr. Wagner of GoldenTree. Others who worked on the East Coast started over, including Jay R. Bloom, Dean C. Kehler and Andrew R. Heyer, who run the highly successful Trimaran Capital Partners. FIFTEEN years later, they are bonded by more than history. One just raised $1.5 million for a charity related to a family illness; a substantial amount came from Drexel people. "What do you say to that?" he said, asking not to be identified. Chris Andersen, a senior banker in the New York office when Drexel collapsed, has a Christmas party every year in the Versailles Room at the St. Regis. Of the 250 people who came last year, more than half had been at Drexel. "The culture, at its core, was almost a religious fervor for what we were doing and the power to transform things," said Mr. Andersen, who founded G. C. Andersen Partners, a merchant banking firm. And few jumped as the ship was sinking. "It was us against everyone else," said Mr. Heyer of Trimaran. "You couldn't have infighting if you were taking on the world." Mr. Virtue, who ran the high-yield business, and then banking, at Bankers Trust, now part of Deutsche Bank , before starting MidOcean, said: "There was a sense that we were abandoned orphans. We kept tabs on each other." The alumni work together on deals and say that their close ties allow them to execute tough transactions in less time. For example, when Jonathan Coslet, a partner at Texas Pacific Group and a former Drexel financial analyst, bought J. Crew in a highly leveraged deal in 1997, the banker working on the deal was Mr. Lanigan, then at Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette. The company received complex financing for the deal from Trust Company of the West, where Mr. Attanasio and two other former Drexel employees - Jean Marc Chapus and Mr. Beyer (Mr. Stevens's former boss) - were involved. Mr. Chapus is managing partner at TCW, where Mr. Beyer is the president. When it came time for a second financing, Texas Pacific Group turned to Black Canyon Capital L.L.C., an investment fund run by Mr. Lanigan and backed by the principals at Canyon Capital Advisors. It financed the full $275 million. Mr. Milken, of course, has also remained in the spotlight. After serving his prison term, he received a diagnosis of prostate cancer. He successfully battled cancer and has been active in the research arena, gracing the cover of Fortune magazine last month alongside Lance Armstrong. Many former Drexel employees speak glowingly of Mr. Milken. "He's so brilliant, it's like getting near the sun," Mr. Wagner said. Mr. Virtue added: "He was the best visionary Wall Street every had." But in an odd way, some former Drexel young guns are equally grateful that the firm collapsed when it did. "When you were part of the Drexel franchise, you weren't sure if it was Drexel" or you, Mr. Coslet said. "Now they have made a name for themselves and it's nice for them to say: 'It was my innovation and my talent. I did it on my own.' " Of course, they all took from the experience a powerful lesson, one that might have served them as well as any expertise they absorbed during their Drexel days. "There's a difference between being very competitive and can-do, and winning at all costs," Mr. Wagner said. "All costs is costly." Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company

RENT STEVENS did not sleep on that February weekend in 1990. A newly minted Wharton School M.B.A., Mr. Stevens had recently joined Drexel Burnham Lambert, the swashbuckling investment bank that dominated the market for financing risky companies. That Sunday, after working on a deal nonstop for 48 hours, he received an ominous telephone call from a managing director, telling him to go home. He was dumbfounded. Deals were over when they were over, he said, and no one at Drexel slept until they were. The next morning, Mr. Stevens arrived at 5:30 at Drexel's office in Beverly Hills to find his boss, Robert Beyer, sitting in his chair. "You're going to hear some pretty difficult things today," he recalled Mr. Beyer telling him. "A lot of them will be true. Don't worry, you'll be fine." Within the hour, Mr. Stevens learned that Drexel, once the most profitable and feared bank on Wall Street, had a liquidity crisis. By evening, the firm would be bankrupt. Later called the "St. Valentine's Day massacre," the bankruptcy left more than 5,700 people in Beverly Hills and New York unemployed and potentially tainted by their association with an institution considered by many people at the time to be defiant, greedy and criminal. That perception, of course, did not come out of thin air. In December 1988, Drexel agreed to plead guilty to six felony counts and to pay a $650 million fine. Three months later, Michael R. Milken, the firm's legendary junk-bond trader, was indicted on 98 charges, including racketeering. He later pleaded guilty to six felony counts, paid $600 million in fines and restitution and served two years in prison. But what became of Mr. Stevens and his co-workers? Today, almost exactly 15 years after the firm's demise, he and many other young employees swept up in the Drexel diaspora have risen to prominent positions on Wall Street. Mr. Stevens is the head of leveraged finance at the Jefferies Group , an investment bank known for lining up complex financing for high-risk companies. Not coincidentally, his boss - Richard B. Handler, the chief executive of Jefferies - was a 28-year-old trader at Drexel when the firm blew up. Several other former Drexel employees are managing billions for pension funds, endowments, wealthy people and one another - often using junk bonds. Mark L. Attanasio, a senior vice president at Drexel when it collapsed, is a managing partner at Trust Company of the West, a $109.7 billion money management firm. Last month, he bought the Milwaukee Brewers for more than $220 million. Interviews with more than two dozen former employees showed that, far from being embarrassed by their connection to Drexel, most retain an almost cultlike devotion to the firm and much of what it stood for. Few of them were crucial players in building Drexel's core franchise, junk bonds. And few of them were especially close to Mr. Milken, who has since survived cancer, established two major foundations devoted to cancer research and become a major investor in an education initiative, Knowledge Universe Inc. But to a person, they all described their Drexel DNA as a crucial factor in their success today. "It showed you the sky was the limit," Mr. Handler said. "You realized you could make a difference in finance. The sheer volume of deals, the market share you could have, your ability to add value to clients, how you could drive your competition nuts, also how much wealth creation was possible." A HANDFUL of Drexel's most senior managers also went on to make names for themselves. Perhaps the best known is former Drexel trader Gary Winnick, who founded Global Crossing, the onetime telecom giant that imploded under a mountain of debt in January 2002. Mr. Winnick cashed in more than $700 million in stock before the firm went belly up. Another veteran star is Leon D. Black, founder of Apollo Management, one of the most respected names in the buyout world. He made his fortune buying the bankrupt portfolio of Executive Life, the insurer. Apollo now manages more than $13 billion, registering compound annual returns of more than 40 percent since 1990 on the $12 billion it has invested. But it is only recently that the younger members of the firm - associates and executive vice presidents, vice presidents and young managing directors - have made their mark. They include Peter J. Nolan, Jonathan D. Sokoloff and John G. Danhakl - all 20-something associates when the firm went bust - who now run Leonard Green & Partners, a private equity shop in Los Angeles that manages $3.7 billion and has posted stellar returns, almost 40 percent a year over the past 16 years. Another is Ken Moelis, who had more seniority at Drexel - though still in his 20's when the firm collapsed - and now is joint global head of investment banking at UBS. The list goes on. The money being made in the credit markets by former Drexel employees is vindication to some former managers, who said they felt that the firm was destroyed unnecessarily. "One prosecutor said to me in 1990, 'With compensation levels like this, this has to be a den of thieves. You couldn't make this much money,' " recalled a former manager who asked not to be identified. "I said, 'Compensation levels are lower than what they will be doing 10 years from now.' " He was right, of course: he and his fellow alumni are making more money today than they ever dreamed during their Drexel days. Mr. Handler's stock and options in Jefferies alone are worth almost $200 million, and Jefferies is one of the best-performing financial stocks on the New York Stock Exchange. The Leonard Green group has returned more than $1.4 billion to investors over the past two years, with each of the three managing partners taking home somewhere in the range of $100 million each. One former government official who was involved in the Drexel case said he was not surprised that many of the alumni had prospered. "The sad thing about Drexel was that a lot of their business was untainted by this, but when it blew up it all blew up," said Gary Lynch, now the general counsel at Credit Suisse First Boston. The legacy of Drexel, gray to the outside world, is as white as snow to the group: It was an institution where hard work and good ideas were rewarded, hierarchies were absent, talent abounded and the potential to be very, very, rich was palatable, former employees said. They recall exactly where they were the morning the firm went bankrupt - as well as the details from the steamy party later that week at the Sugar Shack, a Los Angeles bar, now defunct, where mai tais flowed generously and sex was rampant, several employees recalled. Some still remember their Drexel seniority rank precisely and offer that information voluntarily: 15th to be hired in corporate finance in New York, said one; 10th in trading in Beverly Hills, said another. Almost everyone in the group owns some Drexel memorabilia: a chair, a desk, a computer, all bought or taken during the bankruptcy. And while many were reluctant to be interviewed for this article, once seated, they could not stop talking. To be sure, nostalgia about Drexel's rise and fall is not universal, especially among senior managers. One senior trader who worked with Mr. Milken on his famous X-shaped trading desk and asked not to be identified said: "There were those who sat on the X and those who didn't. There were those who were hired by Mike and those who were not." As for the fond memories of others, he said: "They did not appear before a grand jury. They did not lose millions in stock." No matter what they think of Drexel, however, former employees and other Wall Street watchers seem to agree on this much: there may never be another firm quite like it. "Drexel had a certain chutzpah that hasn't been seen since," said Charles R. Geisst, a Wall Street historian at Manhattan College. "People seem to forget it was the only major financial firm to be shut down by regulators. That's a strong message that chutzpah shouldn't continue." And by most accounts, it hasn't. By the mid-1980's, Drexel was the nexus of the nation's high-yield bond boom and takeover frenzy. Corporate raiders and entrepreneurs like T. Boone Pickens and Ted Turner and Ronald O. Perelman were making plays for companies far bigger than their own. They financed these takeovers with junk bonds, for which Mr. Milken had created a market. The firm - many would say Mr. Milken alone - helped build the cellular, video game and cable industries, including companies like CNN, MCI and McCaw Communications. In 1980, Drexel underwrote 48 high-yield deals that brought in $1.6 billion. In 1989, the firm did 100 deals worth $23.2 billion. Drexel's share of the junk bond market was 40 to 60 percent throughout the decade, according to Thomson Financial. It was not until 1987 that a rival, Credit Suisse First Boston, posted a market share in the double digits. Not surprisingly, Drexel attracted top Ivy League talent. "It was the hot place to go, especially the Beverly Hills office," said Mark Lanigan, who graduated from Harvard Business School in 1986 and now runs an investment fund seeded by another hedge fund group run by former Drexel employees. "They were shaking up the world. Every other day you opened The Wall Street Journal and Drexel was helping to launch a hostile takeover or helping an established company defend itself." Most of the junior bankers chose Drexel over other top-flight banks. They picked it because they thought they could learn more, advance faster, make more money and - corny as it sounds, even on Wall Street - become part of history. "Drexel was tied to a rocket," said Leon Wagner, chairman of GoldenTree Asset Management, a $6.5 billion money management firm, who joined Drexel's high-yield trading desk in 1986 from Lehman Brothers . "Just to be able to sit on the desk and see the calls start at 4:15 in the morning, Boesky and Perelman and Diller and Murdoch," he said referring to Ivan Boesky, the arbitrageur; Mr. Perelman, of Revlon ; Barry Diller, now chairman of IAC/InterActiveCorp, and Rupert Murdoch of the News Corporation . Because the firm controlled the market, young associates were thrown on big deals and told to execute them. "I learned more in five years than I have in the subsequent 15," was a typical observation among the former Drexel employees interviewed. Mr. Attanasio, who made his fortune selling his fund, Crescent Capital, to Trust Company of the West, said, "We were the market, so you learned the market." Frederick H. Joseph, Drexel's former chief executive, who is now managing director and co-head of investment banking at Morgan Joseph & Company, the boutique investment bank, likened the experience to being at a top-notch university. "Harvard is as good as it is because of the people there," he said in an interview. "It's a favorable vicious cycle." There was the money, too - lots of it. The parking lots at the Beverly Hills office were filled with red and yellow Porsches, Ferraris and BMW's. And Drexel knew how to have a party. At the firm's famous Predators' Ball, where it entertained corporate titans, members of the younger generation said they ran around taking notes, gawking at the crowd. Frank Sinatra performed in 1984, Diana Ross in 1985. Star power at credit conferences was rare at the time; the employees thought it was cool. Despite the controversy engulfing the firm in 1990, few employees saw the end coming. Mr. Moelis was skiing with clients in Colorado. Mr. Wagner found out on the Friday before the implosion from his wife. Mr. Attanasio had been in Germany the previous week doing due diligence on a deal. It was by no means immediately apparent that Drexel's young associates and vice presidents were employable. "You had been in Chernobyl," Mr. Nolan said. Many of them kept working on Drexel business: Chris Kanoff, now head of corporate finance at Jefferies, promised to finish a deal for a client and, using the law offices of Latham & Watkins, finished it in eight weeks. Others scrambled to find jobs elsewhere after the bankruptcy. One group went to Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette. Another went to Jefferies, and a third started Canyon Capital Advisors, now a successful $7 billion hedge fund. Mr. Sokoloff joined Leonard Green, and two others would do so later. Some regrouped back East, including Ted Virtue, now the chief executive of MidOcean Partners, a $3 billion private equity fund, and Mr. Wagner of GoldenTree. Others who worked on the East Coast started over, including Jay R. Bloom, Dean C. Kehler and Andrew R. Heyer, who run the highly successful Trimaran Capital Partners. FIFTEEN years later, they are bonded by more than history. One just raised $1.5 million for a charity related to a family illness; a substantial amount came from Drexel people. "What do you say to that?" he said, asking not to be identified. Chris Andersen, a senior banker in the New York office when Drexel collapsed, has a Christmas party every year in the Versailles Room at the St. Regis. Of the 250 people who came last year, more than half had been at Drexel. "The culture, at its core, was almost a religious fervor for what we were doing and the power to transform things," said Mr. Andersen, who founded G. C. Andersen Partners, a merchant banking firm. And few jumped as the ship was sinking. "It was us against everyone else," said Mr. Heyer of Trimaran. "You couldn't have infighting if you were taking on the world." Mr. Virtue, who ran the high-yield business, and then banking, at Bankers Trust, now part of Deutsche Bank , before starting MidOcean, said: "There was a sense that we were abandoned orphans. We kept tabs on each other." The alumni work together on deals and say that their close ties allow them to execute tough transactions in less time. For example, when Jonathan Coslet, a partner at Texas Pacific Group and a former Drexel financial analyst, bought J. Crew in a highly leveraged deal in 1997, the banker working on the deal was Mr. Lanigan, then at Donaldson, Lufkin & Jenrette. The company received complex financing for the deal from Trust Company of the West, where Mr. Attanasio and two other former Drexel employees - Jean Marc Chapus and Mr. Beyer (Mr. Stevens's former boss) - were involved. Mr. Chapus is managing partner at TCW, where Mr. Beyer is the president. When it came time for a second financing, Texas Pacific Group turned to Black Canyon Capital L.L.C., an investment fund run by Mr. Lanigan and backed by the principals at Canyon Capital Advisors. It financed the full $275 million. Mr. Milken, of course, has also remained in the spotlight. After serving his prison term, he received a diagnosis of prostate cancer. He successfully battled cancer and has been active in the research arena, gracing the cover of Fortune magazine last month alongside Lance Armstrong. Many former Drexel employees speak glowingly of Mr. Milken. "He's so brilliant, it's like getting near the sun," Mr. Wagner said. Mr. Virtue added: "He was the best visionary Wall Street every had." But in an odd way, some former Drexel young guns are equally grateful that the firm collapsed when it did. "When you were part of the Drexel franchise, you weren't sure if it was Drexel" or you, Mr. Coslet said. "Now they have made a name for themselves and it's nice for them to say: 'It was my innovation and my talent. I did it on my own.' " Of course, they all took from the experience a powerful lesson, one that might have served them as well as any expertise they absorbed during their Drexel days. "There's a difference between being very competitive and can-do, and winning at all costs," Mr. Wagner said. "All costs is costly." Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company