Friday, April 08, 2005

Friday, April 08, 2005

THE FINANCIAL PAGE ALL TOGETHER NOW by James Surowiecki Issue of 2005-04-11 Posted 2005-04-04 In 1979, Masaru Ibuka, the co-founder of Sony, asked the company?s engineers to make him a portable stereo cassette player that he could take on a plane. Within a few days, the engineers had delivered a prototype. The headphones were gigantic, and the device required special batteries, but it worked, and when Akio Morita, Sony?s C.E.O., saw it, he realized that this was more than a gimmick?it had the potential to change the way people listened to music. In a matter of months, Sony launched the Walkman, one of the most successful products in history, and the story came to epitomize what made the company great: innovation instead of imitation, a dedication to big ideas, and a willingness to pursue its obsessions no matter what others thought. A quarter century later, Sony is still pursuing its own obsessions, but it hasn?t produced anything like the Walkman for a long time. Today, Sony is known for floundering into new markets, not for creating them. Its televisions, music players, and portable devices?the old mainstays?no longer lead the pack, high price tags notwithstanding. Its profits have shrunk, and its stock price is a third of what it was five years ago. Last month, the company replaced its C.E.O. with Howard Stringer, the head of its entertainment business, who?s neither an engineer nor Japanese. The old ways, apparently, will no longer do. Companies often become victims of their own mythologies. Sony?s track record of game-changing inventions?the transistor radio, the Walkman, the Trinitron?led it to believe that success lay in self-sufficiency and absolute control. Sony?s ideal future was one in which just about everything?TVs, DVD players, cameras, computers, stereos, handhelds, digital songs?bore the Sony brand. The company became an exemplar of what?s sometimes called the ?Not Invented Here? syndrome: if it wasn?t invented at Sony, the company wanted nothing to do with it. ?Not Invented Here? is an old problem at Sony. The Betamax video tape recorder failed in part because the company refused to coöperate with other companies. But in recent years the problem got worse. Sony was late in making flat-screen TVs and DVD recorders, because its engineers believed that, even though customers loved these devices, the available technologies were not up to Sony?s standards. Sony?s cameras and computers weren?t compatible with the most popular form of memory, because Sony wanted people to use its overpriced Memory Sticks. Sony?s online music service sold files in a Sony-only format. And Sony?s digital music players didn?t play MP3s, which is a big reason that the iPod became the Walkman?s true successor. Again and again, Sony?s desire to control everything kept it from controlling anything. To be fair, ?Not Invented Here? has an excellent pedigree. For much of the twentieth century, innovation was dominated by big corporations?G.E., Dupont, I.B.M., A.T. & T.?which had gleaming research laboratories and armies of engineers who churned out world-altering creations. But that era is gone. Although successful companies still invest heavily in research and development, they increasingly collaborate with and borrow from others. R. & D. budgets have shrunk at many big companies (which now routinely form R. & D. alliances), and small companies have picked up the slack. Firms that were once exemplars of going it alone have dedicated themselves to playing well with others. Procter & Gamble now gets more than thirty per cent of its innovations from outside. Pharmaceutical companies rely more and more on partnerships with small biotechs to come up with new drugs. Intel, looking for new ideas, invests hundreds of millions of dollars a year in venture capital. I.B.M. has made ?strategic alliances? a cornerstone of its business. Even Apple Computer?once the most imperially self-reliant of companies?has changed. Steve Jobs used to fantasize about controlling everything down to the sand in Apple?s computer chips. Today, Apple works contentedly with companies like Motorola and Hewlett-Packard. The trend, in other words, is toward what Henry Chesbrough, a business professor at Berkeley, has dubbed ?open innovation.? With so many companies investing so much money and energy in innovation, it?s hard for any one of them to consistently outsmart the rest. And technologies are so complex that it?s impractical for a company to gather all the resources it needs under one roof. The spirit of collaboration extends to customers, too. In the new book ?Democratizing Innovation,? Eric von Hippel, a management professor at M.I.T., shows that, in fields ranging from surgical instruments and software to kite surfing, customers often come up with new products or new ways of using old ones. Some companies encourage their customers to modify their merchandise. Others, however, do not: when a devoted user of the Aibo, Sony?s robot dog, wrote applications that would allow the Aibo to dance to music, Sony threatened the man with a lawsuit. Ultimately, Sony doesn?t have much choice: it will either change or continue to come up short. Companies are a little like nations. In an era of globalization, a healthy economy relies on a steady flow of ideas, resources, and capital from outside. So it goes for a big company, in an era of open innovation. Sony should know. While its mythology is all about self-reliance, its history is full of acquisition, collaboration, and partnership. The transistor radio, the color TV, the compact disk: Sony didn?t invent any of these on its own. But it did figure out how to make billions of dollars selling them. If Howard Stringer wants to put Sony right, he should take a hard look at that dancing dog. ?James Surowiecki

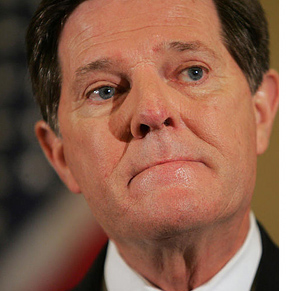

Maureen Dowd

OP-ED COLUMNIST

The Passion of the Tom

By MAUREEN DOWD

WASHINGTON

Before, Republicans just scared other people. Now, they're starting to scare themselves.

When Dick Cheney tells you you've gone too far, you know you're way over the edge.

Last week, the vice president told The New York Post's editorial board that Tom DeLay should not have jumped ugly on the judges who refused to order that Terri Schiavo's feeding tube be reinserted. He said he would "have problems" with the DeLay plan to get revenge on the judges: "I don't think that's appropriate."

Usually, the White House loves bullies. It embraces John Bolton, nominated as U.N. ambassador, even though, as The Times reports today, the Senate Foreign Relations Committee is reviewing allegations that Mr. Bolton misused intelligence and bullied subordinates to help buttress W.M.D. hokum when he was at State.

But there's some skittishness in the party leadership about the Passion of the Tom, the fiery battle of the born-again Texan to show that he's being persecuted on ethics by a vast left-wing conspiracy. Some Republicans are wondering whether they need to pull a Trent Lott on Tom DeLay before he turns into Newt Gingrich, who led his party to the promised land but then had to be discarded when he became the petulant "definer" and "arouser" of civilization. Do they want Mr. DeLay careering around in Queeg style as they go into 2006?

On Tuesday, Bill Frist joined Mr. Cheney in rejecting Mr. DeLay's call to punish and possibly impeach judges - who are already an endangered species these days, with so much violence leveled against them. "I believe we have a fair and independent judiciary today," Dr. Frist said. "I respect that."

Of course, Dr. Frist and the White House still want to pack the federal courts with right-wing judges, but they don't want it to look as if they're doing it because Tom DeLay told them to or because of unhappiness at the Schiavo case.

No matter how much Democrats may be caviling over the House Republicans' attempts to squelch the Ethics Committee before it goes after Mr. DeLay (the former exterminator who pushed to impeach Bill Clinton), privately they're rooting for Mr. DeLay to thrive. They're hoping to do in 2006 what the Republicans did in 1994, when Mr. Gingrich and his acolytes used Democratic arrogance and ethical lapses to seize the House.

Mr. DeLay is seeking sanctuary in Rome at the pope's funeral, and he will hang on to the bitter end. He got thunderous applause from his House colleagues yesterday morning, showing once more that Mr. DeLay, the House majority leader, has a strong hold on the loyalty of those who have benefited from the largesse of his fat-cat friends and from his shrewdness in keeping them in the majority.

"I think a lot of members think he's taking arrows for all of us," Representative Roy Blunt told the press yesterday, backing up Mr. DeLay's martyr complex.

Mr. DeLay lashed out at the latest article questioning his ethics, calling it "just another seedy attempt by the liberal media to embarrass me." Philip Shenon reported in The Times that Mr. DeLay's wife and daughter have been paid more than half a million dollars since 2001 by the DeLay political action and campaign committees.

Republican family values.

The political action committee said in a statement that the DeLay family members provided valuable services: "Mrs. DeLay provides big picture, long-term strategic guidance and helps with personnel decisions."

Political wives are renowned for injecting themselves into the middle of their husbands' office politics at no charge; a lot of members would pay them to go away.

The Washington Post also splashed Mr. DeLay on the front page with an article about a third DeLay trip under scrutiny: a six-day trip to Moscow in 1997 by Mr. DeLay was "underwritten by business interests lobbying in support of the Russian government, according to four people with firsthand knowledge of the trip arrangements."

All the divisions that President Bush was able to bridge in 2004 are now bursting forth as different wings of his party joust. John Danforth, the former Republican senator and U.N. ambassador, wrote an Op-Ed piece in The Times last week saying that, on issues from stem cell research to Terri Schiavo, his party "has gone so far in adopting a sectarian agenda that it has become the political extension of a religious movement."

When the Rev. Danforth, an Episcopal minister who prayed with Clarence Thomas when he was under attack by Anita Hill, says the party has gone too far, it's way over the edge.

E-mail: liberties@nytimes.com

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top

A 3rd DeLay Trip Under Scrutiny

1997 Russia Visit Reportedly Backed by Business Interests

By R. Jeffrey Smith and James V. Grimaldi

Washington Post Staff Writers

Wednesday, April 6, 2005; Page A01

A six-day trip to Moscow in 1997 by then-House Majority Whip Tom DeLay (R-Tex.) was underwritten by business interests lobbying in support of the Russian government, according to four people with firsthand knowledge of the trip arrangements.

DeLay reported that the trip was sponsored by a Washington-based nonprofit organization. But interviews with those involved in planning DeLay's trip say the expenses were covered by a mysterious company registered in the Bahamas that also paid for an intensive $440,000 lobbying campaign.

It is unclear precisely how the money was transferred from the Bahamian-registered company to the nonprofit.

The expense-paid trip by DeLay and four of his staff members cost $57,238, according to records filed by his office. During his six days in Moscow, he played golf, met with Russian church leaders and talked to Prime Minister Viktor Chernomyrdin, a friend of Russian oil and gas executives associated with the lobbying effort.

DeLay also dined with the Russian executives and two Washington-based registered lobbyists for the Bahamian-registered company, sources say. One of those lobbyists was Jack Abramoff, who is now at the center of a federal influence-peddling and corruption probe related to his representation of Indian tribes.

House members bear some responsibility to ensure that the sponsors for their travel are not masquerading for registered lobbyists or foreign government interests, legal experts say. House ethics rules bar the acceptance of travel reimbursement from registered lobbyists and foreign agents.

In this case, travel funds did not come directly from lobbyists; the money came from a firm, Chelsea Commercial Enterprises Ltd., that funded the lobbying campaign, according to the sources. Chelsea was coordinating the effort with a Russian oil and gas company -- Naftasib -- that has business ties with Russian security institutions, the sources said.

Aides to DeLay, who is now the House majority leader, said that despite the presence during the trip of the two registered lobbyists, DeLay thought the nonprofit organization -- the National Center for Public Policy Research -- was funding the trip on its own. Suggestions to the contrary have come to light in media reports only in the past few weeks, an aide said.

"The trip was initiated by the National Center," spokesman Dan Allen said, "and they were the ones who organized it, planned it and paid for it." Sources connected to the trip say, however, that Abramoff, acting at the behest of his Russian-connected client, Chelsea, brought the idea to the center.

Questions on Three Trips

The 1997 Moscow trip is the third foreign trip by DeLay to be scrutinized in recent weeks because of new statements by those involved that his travel was directly or indirectly financed by registered lobbyists or a foreign agent.

Media attention focused on DeLay's travel last month after The Washington Post reported on DeLay's participation in a $70,000 expense-paid trip to London and Scotland in 2000 that sources said was indirectly financed in part by an Indian tribe and a gambling services company. A few days earlier, media attention had focused on a $106,921 trip DeLay took to South Korea in 2001 that was financed by a tax-exempt group created by a lobbyist on behalf of a Korean businessman.

DeLay on March 18 portrayed criticism of his trips and close ties to lobbyists as the product of a conspiracy to "destroy the conservative movement" by attacking its leaders, such as himself. "This is a huge, nationwide, concerted effort to destroy everything we believe in," DeLay told supporters at the Family Research Council, a conservative Christian group.

The three foreign trips at issue share common elements. The sponsor of the Moscow trip, the Capitol Hill-based National Center for Public Policy Research, also sponsored the later London trip. The center is a conservative group that solicits corporate, foundation and individual donations.

Also, Abramoff not only joined DeLay in Moscow but also helped organize DeLay's subsequent London trip. Abramoff also filed expense reports indicating he paid for some of DeLay's hotel bill in London, according to a copy obtained by The Post.

Edwin A. Buckham, who was DeLay's chief of staff in 1997 and then became a Washington lobbyist for major corporations, participated in two of the three trips. In 1997, he visited Moscow twice -- once with DeLay -- and on one of these trips he returned via Paris aboard a Concorde jet with a ticket he told the Associated Press in 1998 had been financed by the National Center.

Buckham also joined DeLay on the Korea trip. Buckham did not respond to messages left by The Post.

Untangling the origin of the Moscow trip's financing is complicated by questions about the ownership and origins of Chelsea, the obscure Bahamian-registered company that financed the lobbying effort in favor of the Russian government that targeted Republicans in Washington in 1997 and 1998. Those involved in this effort also prepared and coordinated the DeLay visit, individuals with direct knowledge about it said.

In that period, prominent Russian businessmen, as well as the Russian government, depended heavily on a flow of billions of dollars in annual Western aid and so had good reason to build bridges to Congress. House Republicans were becoming increasingly critical of U.S. and international lending institutions, such as the Overseas Private Investment Corporation (OPIC) and the International Monetary Fund, which were then investing heavily in Russia's fragile economy.

Unlike some House conservatives who scorn such support as "corporate welfare," DeLay proved to be a "yes" vote for institutions bolstering Russia in this period. For example, DeLay voted for a bill that included the replenishment of billions of dollars in IMF funds used to bail out the Russian economy in 1998.

A DeLay aide said he tried to reform these institutions through the legislative process. DeLay voted to fund these agencies because their financing was usually included in appropriation bills that he generally supported, the aide said. They also noted that OPIC had the strong backing of the energy industry, including companies from Texas that received OPIC financing.

Meetings in Moscow

The Russian campaign is detailed in disclosures filed with the House by lobbyists. Those records state that Chelsea, with an address listed variously as a post office box on the British island of Jersey -- a tax haven off the French coast -- or a law firm in the Bahamas, paid at least $440,000 to fund lobbying aimed at building "support for policies of the Russian government for progressive market reforms and trade with the United States," according to lobbying registration documents.

The Washington offices of two lobbying and law firms collected the fees. Preston Gates Ellis and Rouvelas Meeds LLP -- where Abramoff then worked -- received $260,000 in 1997 and less than $10,000 in 1998; Cadwalader Wickersham and Taft LLP was paid $180,000 in 1997 and less than $10,000 annually for the next three years, according to the registrations. Their listed lobbying targets included members of the House and Senate and officials of the State Department and the Agency for International Development.

"One of the functions of the lobbying effort was to encourage U.S. policymakers to visit Russia and to learn more about Russia," Ellen S. Levinson, a lobbyist then working on the Chelsea account at Cadwalader, said in an e-mailed response to questions.

She said Preston Gates used its "contacts with policy institutes and congressional offices" to arrange these trips. Preston Gates said in a written statement that it does not comment on its work for clients.

In a Cadwalader memo dated May 6, 1997, and obtained by The Post from another source, Levinson depicted the DeLay trip as one of six organized that year as part of the lobbying effort. Others included an "advance team" that visited Moscow later that month and a visit by "think tank" experts in June. A copy of the memo was sent to Abramoff.

A total of six members of the two lobbying firms participated in these trips, according to those involved. Levinson and two Preston Gates lobbyists were members of the "advance team."

During the third visit, Cadwalader lobbyist Julius "Jay" Kaplan joined DeLay and Abramoff at a "fancy dinner" in Moscow, according to one of those present -- a circumstance first reported last month in an article about the trip in National Journal's Congress Daily.

Breaking with traditional practice for congressmen traveling overseas, DeLay did not contact the State Department in advance or meet with officials at the U.S. Embassy in Moscow regarding his meeting with Chernomyrdin, according to a department spokeswoman who said she checked with 10 people at the embassy then or responsible for facilitating congressional trips.

Allen, DeLay's spokesman, said the State Department was not contacted because "the National Center was responsible for the arrangements on the trip, including setting up the meetings. Beyond that, members of Congress aren't required to have the State Department present at meetings with leaders from other countries."

Last month, Amy Ridenour, director of the National Center, posted a statement on her organization's Web site in response to questions about DeLay's trip to Russia stating that the center itself had "sponsored and paid" for all the expenses associated with it. Ridenour and her husband also took part in the visit.

But a person familiar with planning for the trip said Abramoff -- who has long been close to DeLay -- approached the National Center with the idea for the trip on behalf of Kaplan and his client, Chelsea. That person said the expenses by the center were in turn replenished by "an American trust account affiliated with a law firm" that the person declined to name.

Kaplan declined to be quoted for this article, citing what he called "lawyer-client privilege." But another person with direct knowledge about the trip arrangements said that it was Chelsea -- which had the registered Washington lobbyists in its employ -- that "gave the money to NCPPR to pay for the trip."

This person, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to protect his business interests, added: "I didn't see anything wrong there. All these foundations get money from somewhere, and they give it out." Moreover, the source said, "this was the Russians' way of doing business then -- moving money from one firm to another."

Who Financed Travel?

The question is: Who stood behind Chelsea, and thus ultimately financed the trip? A regular office for the firm could not be located by The Post, in Moscow or at its two listed addresses; its Bahamian registration ended in 2000, officials there said. Efforts by The Post to find the three men -- one Belgian, one British, one Russian -- named in lobbying registrations as Chelsea investors or owners in lobbying disclosures were unsuccessful.

A spokeswoman for Cadwalader, Paula Zirinsky, said the firm had no contact information for anyone from Chelsea, because "persons that worked on that matter have not been with the firm since 1997." Jonathan Blank, managing partner of the Washington office for Preston Gates, similarly said his firm had no current contact information for Chelsea.

In interviews, however, five individuals with direct knowledge of the lobbying effort separately described executives of a diversified Russian energy firm known as Naftasib as being intimately involved in the lobbying.

Naftasib, which oversees interests in mining, oil and gas, construction and other enterprises from a four-story unmarked building in downtown Moscow, says it is a separate company from Chelsea but acknowledges seeking to cultivate friends in Washington in 1997.

In a written statement issued Friday in response to questions from The Post, Marina Nevskaya, Naftasib's deputy general manager, explained that her firm "wanted to foster better understanding between our country and the United States, and felt that if these trips were successful they would foster a better overall climate that could ultimately benefit Naftasib as well as other Russian enterprises."

Nevskaya said her company "did not finance in any manner" the DeLay trip or the others described in Levinson's memo. But she said Naftasib "did host and pay for some dinners for participants in some of the trips, organized a few other special events . . . and may have provided minor courtesies, such as some auto pickups and dropoffs for some visitors during one or more of the trips."

She also acknowledged providing "advice about trip logistics" before they occurred and meeting trip participants. Nevskaya did not offer details, but those involved in organizing DeLay's trip said he met with Nevskaya and was escorted around Moscow by the general manager of Naftasib, Alexander Koulakovsky. DeLay has also met with Nevskaya and Koulakovsky in Washington since then, according to several sources with direct knowledge of the contact.

During the June 1997 trip to Moscow by "think tank" experts -- one of the scheduled visits listed in Levinson's memo -- several participants said they got the impression that Preston Gates was the organizer, Naftasib was the ultimate financier and that the trip was a dry run for DeLay's visit.

"It was done through or under the auspices of NCPPR," said Bart Adams, a North Carolina journalist who joined the expense-paid trip. But he said he recalls hearing that "the money was coming from a Russian oil company."

David Lowe, an official at the National Endowment for Democracy, said he was recruited to join the trip by the Preston Gates firm; former Senate aide James P. Lucier, who also was on the trip, said Naftasib's executives played such a large role that they "seemed to be the clients of Preston Gates," a claim the firm denies. "Some American investment or tie was the end goal," said a third participant, "and the plan was to bring over some congressmen" later.

A publicist who works for Abramoff attorney Abbe David Lowell said Abramoff did lobby for Chelsea but not for Naftasib. The publicist said Abramoff thought "bringing a greater understanding of Russia to American decision makers was and is good for America."

The efforts by Naftasib's executives to curry favor among Republicans -- including DeLay -- sowed controversy at the time among conservatives. A journal published by a Washington think tank, the American Foreign Policy Council, claimed within a few days after DeLay's trip ended that it was actually "sponsored" by Naftasib. The journal -- the Russian Reform Monitor -- also highlighted what it characterized as Naftasib's tight connections to the Russian security establishment.

The journal quoted promotional literature for Naftasib that described the firm as a major shareholder in Gazprom, the state-controlled oil and gas giant. The literature also said Natfasib's largest clients were the ministries of defense and internal affairs. The literature also states that Nevskaya was an instructor at a school for Russian military intelligence officers. She declined to address those claims in response to questions from The Post.

Steve Biegun, who was then a senior Russia expert for the Senate Foreign Relations Committee and later served as executive secretary to the National Security Council during President Bush's first term, said he deliberately blocked a meeting that Nevskaya sought with Jesse Helms (R-N.C.), then the committee chairman.

"They were a client of the lobbying firm Preston Gates," said Biegun, who is now a Ford Motor Co. vice president for international governmental affairs. "I made some calls . . . and got enough warning signs" to ensure that Helms avoided dealing with the firm. Biegun said the information he obtained from his sources was "nothing that would stand up in court" but he worried that in this period, "a lot of unsavory figures from Russia were buying their way into meetings and getting their pictures taken, to put on the wall back in Moscow."

"I just had my doubts, and nobody did anything to allay them," Biegun said. "I did not know who either of them really were."

Asked to comment, Blank, Preston Gates's Washington managing partner, said in a written statement: "Chelsea was our only client. Naftasib was not our client. We did work with Naftasib representatives when their interests coincided with our client's." Blank added that "we are confident that the individuals still with the firm who were involved at the time acted ethically, appropriately, and in service of the client."

Abramoff left Preston Gates at the end of 2000.

OP-ED CONTRIBUTOR

In the Name of Politics

By JOHN C. DANFORTH

St. Louis ? BY a series of recent initiatives, Republicans have transformed our party into the political arm of conservative Christians. The elements of this transformation have included advocacy of a constitutional amendment to ban gay marriage, opposition to stem cell research involving both frozen embryos and human cells in petri dishes, and the extraordinary effort to keep Terri Schiavo hooked up to a feeding tube.

Standing alone, each of these initiatives has its advocates, within the Republican Party and beyond. But the distinct elements do not stand alone. Rather they are parts of a larger package, an agenda of positions common to conservative Christians and the dominant wing of the Republican Party.

Christian activists, eager to take credit for recent electoral successes, would not be likely to concede that Republican adoption of their political agenda is merely the natural convergence of conservative religious and political values. Correctly, they would see a causal relationship between the activism of the churches and the responsiveness of Republican politicians. In turn, pragmatic Republicans would agree that motivating Christian conservatives has contributed to their successes.

High-profile Republican efforts to prolong the life of Ms. Schiavo, including departures from Republican principles like approving Congressional involvement in private decisions and empowering a federal court to overrule a state court, can rightfully be interpreted as yielding to the pressure of religious power blocs.

In my state, Missouri, Republicans in the General Assembly have advanced legislation to criminalize even stem cell research in which the cells are artificially produced in petri dishes and will never be transplanted into the human uterus. They argue that such cells are human life that must be protected, by threat of criminal prosecution, from promising research on diseases like Alzheimer's, Parkinson's and juvenile diabetes.

It is not evident to many of us that cells in a petri dish are equivalent to identifiable people suffering from terrible diseases. I am and have always been pro-life. But the only explanation for legislators comparing cells in a petri dish to babies in the womb is the extension of religious doctrine into statutory law.

I do not fault religious people for political action. Since Moses confronted the pharaoh, faithful people have heard God's call to political involvement. Nor has political action been unique to conservative Christians. Religious liberals have been politically active in support of gay rights and against nuclear weapons and the death penalty. In America, everyone has the right to try to influence political issues, regardless of his religious motivations.

The problem is not with people or churches that are politically active. It is with a party that has gone so far in adopting a sectarian agenda that it has become the political extension of a religious movement.

When government becomes the means of carrying out a religious program, it raises obvious questions under the First Amendment. But even in the absence of constitutional issues, a political party should resist identification with a religious movement. While religions are free to advocate for their own sectarian causes, the work of government and those who engage in it is to hold together as one people a very diverse country. At its best, religion can be a uniting influence, but in practice, nothing is more divisive. For politicians to advance the cause of one religious group is often to oppose the cause of another.

Take stem cell research. Criminalizing the work of scientists doing such research would give strong support to one religious doctrine, and it would punish people who believe it is their religious duty to use science to heal the sick.

During the 18 years I served in the Senate, Republicans often disagreed with each other. But there was much that held us together. We believed in limited government, in keeping light the burden of taxation and regulation. We encouraged the private sector, so that a free economy might thrive. We believed that judges should interpret the law, not legislate. We were internationalists who supported an engaged foreign policy, a strong national defense and free trade. These were principles shared by virtually all Republicans.

But in recent times, we Republicans have allowed this shared agenda to become secondary to the agenda of Christian conservatives. As a senator, I worried every day about the size of the federal deficit. I did not spend a single minute worrying about the effect of gays on the institution of marriage. Today it seems to be the other way around.

The historic principles of the Republican Party offer America its best hope for a prosperous and secure future. Our current fixation on a religious agenda has turned us in the wrong direction. It is time for Republicans to rediscover our roots.

John C. Danforth, a former United States senator from Missouri, resigned in January as United States ambassador to the United Nations. He is an Episcopal minister.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top

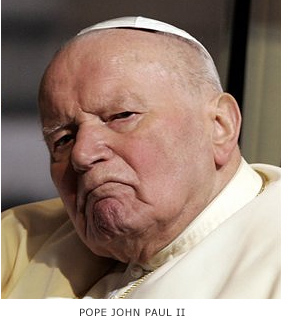

The bully pope

John Paul II ruled the Catholic Church as an autocrat, and those who crossed him often suffered greatly for it.

By Colman McCarthy

April 8, 2005 | As the secretly elected leader of a male-run, land-rich, undemocratic, hierarchic, dogmatically unyielding organization headquartered in a second-rate European country, Pope John Paul II had few, if any, worries about accountability. He ruled, accordingly, as an autocrat. Organizationally, who could challenge him? Institutionally, he projected an image of a loving shepherd endlessly traveling to distant pastures to bless the flock.

Watch out, though, if he thought you were straying. Then John Paul would "crook" you by the neck and dispatch you to a stony field where black-sheep dissidents could do penance.

He found victims early in his papacy. Enthroned only two years, the pope decided in 1980 that the Rev. Robert Drinan, a 10-year member of Congress from Massachusetts' 4th District, should get out of politics. Drinan, a Jesuit priest in the Gene McCarthy-Philip Hart wing of the Democratic Party, championed human rights and programs for the poor, and opposed Pentagon militarism. But his voting record on abortion bills wasn't strictly pro-life.

The archbishop of Boston had no problem with Drinan's being in politics. His Jesuit superiors had no problem. Paul VI, the previous pope, had no problem. Nor did the voters. But John Paul did. Drinan, who vainly asked the pope to reconsider his decree, obeyed and left Congress.

In 1980 John Paul had other troublesome priests on his hit list. Archbishop Oscar Romero was one. A former conservative who moved to the liberation-theology left when he saw up close the poor killing the poor in El Salvador, Romero was under surveillance by the Vatican. Jonathan Kwitny, a Wall Street Journal investigative reporter and author of "Man of the Century: The Life and Times of Pope John Paul II," wrote that the pope "was disturbed about Romero." Cardinals in the Vatican plotted to reassign Romero elsewhere in Latin America. Days after Romero's March 24, 1980, murder, John Paul telegrammed the president of the Salvadoran Episcopal Conference to express grief at the "sacrilegious assassination." "Not one word of praise," wrote Kwitny, was offered "for the slain archbishop." Speaking to crowds in St. Peter's Square, the pope then expressed heartfelt grief for Catholic martyrs -- in Chad, not El Salvador. Kwitny wrote: "John Paul's treatment of Archbishop Romero, and his continued treatment of Romero's memory, are an injustice like no other he has done anyone."

Another victim of papal wrath was the Rev. William Rewak, a Jesuit who served for more than 20 years as president of two colleges. In September 1998, his order appointed him president of the Jesuit School of Theology in Berkeley, Calif. Neither they nor Rewak foresaw any objections from the Vatican, which had final hiring and firing power because the school offers pontifical degrees. But papal underlings uncovered some 20-year-old writings of Rewak's on married clergy and women's ordination that differed mildly from the pope's view. It was enough to quash the pending appointment, even after Rewak left a college presidency to take the job.

John Paul was a Catholic fundamentalist. Small wonder he is being hailed by Pat Robertson, Patrick Buchanan and George W. Bush. The same ruler who bullied Drinan, Romero and Rewak -- only three of many, many -- had no objections when prelates of his own stripe dabbled in politics. During last year's U.S. presidential campaign, for instance, Bishop Michael Sheridan of Colorado Springs, Colo., thundered to his 120,000-member diocese: "Anyone who professes the Catholic faith with his lips while at the same time supporting legislation or candidates that defy God's law makes a mockery of that faith and belies his identity as a Catholic." Voters who defy church teachings "jeopardize their salvation."

Not only could John Kerry, Ted Kennedy, Patrick Leahy and other Catholic pro-choice senators spend eternity in hell but voters might burn with them.

The sorriest scandal during John Paul's long stint was his refusal to transform Roman Catholicism into a peace church. It remains polluted by the just-war theory, devised by Augustine in the fifth century and advanced by Thomas Aquinas in the 13th. The pope opposed the two U.S. invasions of Iraq, but he never renounced the notion that war can be justified. French Cardinal Jean-Louis Tauran said during the start of the second Iraq war that "the Holy See is not pacifist." The church has more than 1,500 canon laws. Not one applies to war-making.

With large numbers of American Catholic priests, nuns and lay people imprisoned for antiwar civil disobedience during the 27 years of his papacy, John Paul never once spoke out in their support. Nor did he visit any of them in prison during his seven trips to this country. Those Catholics who want membership in a peace church have a better chance with the Quakers, Mennonites or Church of the Brethren.

These old-line peace churches aren't much for dogmas, decrees, doctrines or other rubrics favored by John Paul. They favor loving their enemies, laying down their swords, sharing their wealth and doing good to those who harm them -- odd notions indeed, but ones that helped an upstart religion get footing 2,000 years back.

At best the chances are slim that the next pope, either spiritually or organizationally, will be able to undo the deep factionalism created by John Paul. Recent years have seen shelves sagging under the weight of books about the church's problems. A partial listing includes "Catholics in Crisis" by James Naughton, "The Dysfunctional Church" by Michael Crosby, "Toward a New Catholic Church" by James Carroll, "The New Anti-Catholicism" by Philip Jenkins, "Will Catholics Be Left Behind?" by Carl E. Olson, "Papal Sin" by Garry Wills, "Goodbye, Good Men" by Michael Rose, "Goodbye Father" by Richard Schoenherr, "Tomorrow's Catholics/Yesterday's Church" by Eugene Kennedy, "In Search of American Catholicism" by Jay Dolan, "A People Adrift: The Crisis of the Roman Catholic Church in America" by Peter Steinfels, "The Coming Catholic Church" by David Gibson and "Why Catholics Can't Sing" by Thomas Day.

The most prominent faction, at least at the moment, is the traditionalist one that has been summoned by the media to the airwaves and Op-Eds, there to hail the late pope as having been the fearless defender of all the rules that make The One True Church still true and still one. This faction, ever rankled at what Pope John XXIII wrought with the Second Vatican Council of the early 1960s -- every loony idea from altar girls to the handshake of peace at Mass -- saw in John Paul a no-nonsense leader. They cheered him for not yielding on the below-the-waist issues: artificial birth control, abortion, homosexuality, gay marriage. The traditionalists tend to be both theologically and politically conservative, with Antonin Scalia, Rick Santorum, Patrick Buchanan, William Bennett, Sean Hannity, Robert Novak, William F. Buckley, Phyllis Schlafly and Mel Gibson side by side in the pews.

The spiritual Catholics are those who see the papacy as irrelevant to their lives. When they pray, it isn't the prayer of asking, as though God, or Mary hailed by rote, dispensed favors, but the prayer of cooperation: Cooperate with the gifts you've been given and use them to become someone who is other-centered, not self-centered. If anyone speaks for them, it may be Leo Tolstoy in "The Kingdom of God Is Within You": "Christ could certainly not have established the Church. That is, the institution we now call by that name, for nothing resembling our present conception of the Church -- with its sacraments, the hierarchy, and especially its claim to infallibility -- is to be found in Christ's words or in the conception of the men of his time."

The pragmatic Catholics stay grounded in early church Christianity, when it was the works of mercy and rescue that kept the community together and when people practiced communism -- the pure communism of the commune. The lines from the Acts of Apostles speak to them: "All believers were together and had all things in common. And those who had possessions sold them and divided to each person according to need: Not one of them spoke of the property he possessed as his own."

These are the Catholic Worker Catholics, those who carry on the labors of Dorothy Day, who opened not homeless shelters but houses of hospitality. More than 100 of these houses can be found today, 25 years after Day's death, in both large cities and rural farming towns. Pragmatic Catholics remain loyal to the Christ described by Phillips Brooks in 1883: "In the best sense of the word, Jesus was a radical: His religion has so long been identified with conservatism that it is almost startling sometimes to remember that all the conservatives of his own times were against him, that it was the young, free, restless, sanguine, progressive part of the people who flocked to him."

Better than anyone, pragmatic Catholics understand the long-standing quip "Jesus came preaching the Gospel and ended up with the church."

John Paul, the traveling man, was helpless to keep American Catholics in line, however hard he tried. Who else did he have in mind in his railings against consumerism and hedonism? Had he stopped fuming about the rebellious Americans, he might have noticed that, with some millions attending Mass regularly in 19,000 parishes and giving more than $7 billion annually to the Catholic Church, the United States has the flock with the strongest faith in the developed world. David Gibson, a Protestant-born journalist who once worked for Vatican Radio, wrote accurately: American Catholics "are the most religiously observant Catholics in modern-day Christendom, attending church and supporting the pope to a degree that has no parallel in the industrialized world."

Someone might want to clue in the new pope.

About the writer

Colman McCarthy, a former Washington Post columnist, directs the Center for Teaching Peace in Washington. His most recent book is "I'd Rather Teach Peace."

House Majority Leader Tom DeLay, known as the Hammer

Broken Hammer?

Recent revelations of huge sums paid to family members have stung the GOP majority leader. But Tom DeLay was damaged goods long before that.

By Lou Dubose

April 8, 2005 | The laws of political gravity don't seem to apply to Tom DeLay. If they did, the burden of scandal he bears would have sunk him long ago -- and recently things have gotten even worse for the Republican majority leader from Texas. In the week before congressional Republicans made their rash intervention in the Terri Schiavo case, the Washington Post ran no fewer than seven Page One stories about DeLay. The only story that didn't directly connect DeLay to scandal ran under the headline "DeLay Treated for Irregular Heartbeat." More critical reporting followed after Schiavo's death, while DeLay and Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, implied that judges had killed her.

The most recent stories about DeLay include accounts of:

A $106,921 educational and golfing trip that DeLay, his wife and staff took to Korea on the tab of a registered foreign agent -- a violation of House rules. (The money was funneled through a Washington tax-exempt group and the trip arranged by longtime DeLay associate Jack Abramoff.)

A $70,000 golfing trip DeLay took to England and Scotland, paid for by lobbyists and $50,000 solicited from two Indian tribes. (The Indian money was solicited by Abramoff and moved through a Washington think tank he worked with.)

A $57,238 golfing trip to Moscow, underwritten by a Russian lobbying firm hired by a Russian oil and gas company trying to cultivate support in the U.S. Congress. (The money was funneled through the same Washington think tank connected to Abramoff, who traveled to Moscow with DeLay. The trip was arranged by the Rev. Ed Buckham, a lobbyist and former DeLay staffer and spiritual advisor, who also traveled with DeLay to Russia and Korea.)

Approximately $500,000 in political money paid as salaries to DeLay's wife, Christine, and his daughter, Danni Ferro.

It was not a good news week for "the Hammer." But DeLay was damaged goods six months before any of these stories were reported. He had been admonished by the House Ethics Committee three times in the course of one month last year -- a record for unincarcerated members of the House. Three political operatives (one a close associate) who run a Texas political action committee DeLay set up in 2001 are under indictment in Texas -- one of them facing a 99-year sentence. Eight corporations have also been indicted for alleged illegal contributions to DeLay's Texans for a Republican Majority PAC (TRMPAC).

As was first reported here, DeLay himself accepted a $25,000 TRMPAC contribution from a Reliant Energy Corp. lobbyist. (The lobbyist, Drew Maloney, had served on DeLay's House staff before moving on to K Street.) Previously I reported that the Williams Cos., one of the eight corporations under indictment in Texas, had addressed to "Congressman Tom DeLay" a letter conveying "$25,000 for the TRMPAC that we pledged at the June 2, 2002 fundraiser." (Contributing or accepting corporate money for use in a political campaign is against Texas law.)

This month a state district judge in Austin will hand down his decision in a civil case filed by five Democratic state house candidates targeted by DeLay's PAC in the 2002 election. (For an account of that trial and a look at documents that will ultimately be introduced in the TRMPAC criminal trial, see Jake Bernstein's article,"TRMPAC in Its Own Words," in the April 1 issue of the Texas Observer. Bernstein and his colleague Dave Mann previously broke a pay-to-play story in which TRMPAC fundraisers offered donors specific legislation in return for their contributions.)

While DeLay's lawyers and political advisors in Washington nervously await a decision in the civil case involving TRMPAC, they also wonder if the other boot will drop in Texas. That is, will Travis District Attorney Ronnie Earle indict DeLay? The jury (or at least the grand jury) is still out on that one.

But DeLay also has big problems in Washington, where Abramoff and DeLay's former press aide Mike Scanlon, face not one but three separate investigations for an $82 million fraudulent billing scheme that involves six casino-rich Indian tribes.

How, then, does Tom DeLay hang on to power?

The answer to that question involves the two constituencies most indebted to Tom DeLay: The Republican members of the House who selected him to lead them in 2003 and (for the moment) continue to support him; and the Republican campaign and advocacy groups enriched by huge contributions from the same corporate lobbyists and clients who pick up the tab for DeLay, his family and staff to play golf in American Saipan, Scotland, England and Russia.

The loyalty of House Republicans can be traced to 1994. Though he is routinely linked to Newt Gingrich, whose reform movement that same year promised to sweep corrupt Democrats from power, DeLay was never one of Newt's revolutionaries. He had worked on the campaign of Ed Madigan, whom Gingrich defeated in a race for minority whip when Dick Cheney left the House to take a position in the administration of the first President Bush in 1989. Cheney had made DeLay a deputy whip. After DeLay backed Gingrich's opponent in the whip race, Gingrich shut him out of the House leadership.

By 1994, DeLay was back in the game. He formed a political action committee, Americans for a Republican Majority (ARMPAC), and raised $780,000 to invest in Republican House races. Gingrich surpassed him, raising $1.5 million, but DeLay had a second funding source -- lobbyists. By his own admission, in that election he directed more than $2 million in lobby money to Republican candidates. The $2,780,000 bought him the loyalty of the most conservative congressional class elected in modern times.

Since then, he has raised more political money than any other member of Congress and shrewdly spent it on House campaigns to build what he openly calls "a permanent Republican majority." By 2003, when he was at the top of his game and didn't have to compete with his own legal defense fund, DeLay was raising $12,785 a day, according to a report released by the campaign-finance reform group Democracy 21. Today, in a city where size matters, DeLay has a bigger PAC than House Speaker Dennis Hastert and Majority Whip Roy Blunt, both of whom came into House leadership as lieutenants on DeLay's whip team.

Hastert is particularly indebted to DeLay. He ran DeLay's 1995 whip campaign and served as chief deputy whip while DeLay held that office. In 1998 DeLay used his 67-member whip organization to make Hastert speaker, after DeLay's first choice to replace a disgraced Gingrich, Bob Livingston, quit the race when details about his marital infidelity were reported. DeLay has bought and paid for the loyalty of the House.

DeLay's lobby operation is more complicated but equally important to Republican Party hegemony. As described by American Enterprise Institute scholar Norman Ornstein, the K Street Project by which DeLay domesticated the corporate lobby is a "Tammany Hall operation" that ensures only Republicans are hired for big lobbying jobs that pay as much as $1 million a year. Once hired, "everyone is expected to contribute some of that money back into Republican campaigns," Ornstein told me when I was working on a book on DeLay last year. According to Ornstein, DeLay and the K Street project have even locked up the entry-level lobby positions that pay from $150,000 to $250,000 a year -- with the understanding that anyone who gets a job "maxes out" in contributions to Republican candidates and campaigns.

DeLay laid the groundwork for the K Street project by calling corporate lobbyists into his office after he was elected whip in 1995. He sat them down and pointed to their names in a ledger that included contributions they had made to Democrats and Republicans. Then he reminded them that Republicans were in charge and their political giving had better reflect that -- or else. The "or else" was a threat to cut off access to the Republican House leadership.

By 1998, DeLay was telling K Street lobbying firms and trade associations they could hire no more Democrats. To underscore his point, he pulled an important intellectual-property rights bill off the House floor when the Electronics Industries Alliance hired former Rep. Dave McCurdy of Oklahoma. For this act DeLay was privately reprimanded by the House Ethics Committee. But he made his point. The fat lobby positions were henceforth reserved for Republicans. (The EIA refused to back down but negotiated a deal by which it would hire a Republican to work with McCurdy.)

DeLay and the House leadership would later summon lobbyists it had put in positions of power on K Street and order them to work on behalf of the Republican agenda -- including the G.W. Bush tax cuts. So corporate lobbyists became an extension of the Republican whip operation in the House. And, significantly, a profit center for the Republican Party and its ancillary advocacy groups.

The junkets involving Tom DeLay, his wife, his staff and former staffers, are the perks the majority leader has earned for putting this huge funding operation in the field. DeLay has been traveling on the lobby tab for a decade now. But a year ago, two DeLay loyalists created a problem that might be more than even he can manage. The recent scandal involving DeLay's longtime associate and fundraiser Jack Abramoff, and DeLay's former press aide Mike Scanlon, provide a small glimpse into a huge and potentially scandalous Republican operation used to funnel lobby money, and money squeezed out of lobbyists' clients, into accounts controlled by the party.

In the recent Indian gaming scandal, Abramoff and Scanlon sold Tom DeLay's operation to American Indian tribes desperate to protect their gambling operations, according to sources I talked to on three reservations. As proof of DeLay's clout, Abramoff and Scanlon pointed to his role in killing a bill that threatened Indian gaming in 2001. In total, they billed the Indians an astonishing $82 million, more than twice what corporate clients such as General Electric paid for contract lobbying in the same three-year period. Once the two lobbyists established a revenue stream that provided for personal enrichment unlike anything they had ever imagined, they began paying what Sicilians call tributo to the people and organizations who made it all possible.

For example, Abramoff raised $200,000 for George Bush's presidential campaign and donated hundreds of thousands to other Republican candidates. Scanlon, who was paying off college loans when he left DeLay's press office in 1999, contributed $500,000 to the Republican national governors' organization in 2002 -- the largest individual contribution the group received that year.

Abramoff directed the Coushatta Tribe of southwestern Louisiana to contribute $100,000 to an environmental group set up by Gale Norton while she was secretary of the interior. He had the Coushattas donate $20,000 to DeLay's Washington PAC. And $25,000 to Republican anti-tax activist Grover Norquist's Americans for Tax Reform. (In return, the Coushattas got an invitation to a Norquist fundraiser held at the White House.) Suddenly, American Indian tribes that had traditionally made modest political contributions to Democrats were making huge contributions to Republicans. (The two lobbyists had no interest in dirt-poor Plains Indian tribes that operated no casinos.)

So one lobbying organization that got too greedy threatens to sink DeLay's K Street operation -- and DeLay with it. When the remarkable reporting of Shawn Martin of the American Press in Lake Charles, La., made its way to the front page of the Washington Post, the majority leader was confronted with a crisis he couldn't manage.

To keep things under control for the moment, Hastert has replaced errant Republican members of the Ethics Committee who voted to admonish DeLay with one of his loyalists and two members who had contributed to DeLay's legal defense fund. To further protect DeLay (and perhaps Rep. Bob Ney of Ohio, who took a $50,000 Scottish golf trip paid for Indians while he promised to carry a bill for a Texas tribe), Hastert changed the rule that required investigations to automatically begin 45 days after any member of the House files a complaint. An Ethics Committee investigation now requires a majority vote, and the committee is evenly divided between Democrats and Republicans.

A year ago, Sen. John McCain began an aggressive Senate Indian Affairs investigation of Abramoff and Scanlon, which included the release of 100 pages of their internal documents, several of which indicated DeLay's involvement. Recently, when it was reported that one Indian tribe had written $25,000 checks to Republican Sens. Sam Brownback and Conrad Burns, McCain reassured his colleagues that his investigation would be limited to the lobbyists -- not members of Congress.

DeLay can control the Congress. But he has problems with the courts and the press. Abramoff and Scanlon are also under investigation by two federal grand juries and a FBI task force that includes three other federal agencies. The Indian tribes are pursuing their own lawsuits. Criminal trials of DeLay's Texas operatives will probably begin in the summer. DeLay's two TRMPAC operatives also face a civil suit, as soon as they get their criminal proceeding behind them. Litigation provides journalists documents they can never otherwise obtain because, unlike lawyers, they have no subpoena power. The nation's big news organizations are following paper trails to various DeLay scandals. The majority leader is beginning to look like a bad story about to break every week.

Will DeLay survive? He brings in millions of dollars and is an indefatigable party builder who last year added six Texas seats to the Republican House majority by redrawing congressional district lines in Texas. So it's hard for House Republicans to say goodbye. But as DeLay's name becomes synonymous with political corruption, they might have no choice. If the party decides DeLay is too much a liability to carry into the off-year elections, a delegation of his colleagues will pay him a visit at his Capitol office just off Statuary Hall and thank him for all he's done for the party.

About the writer

Lou Dubose is a former editor of the Texas Observer and coauthor, with Jan Reid, of "The Hammer: Tom DeLay, God, Money and the Rise of the Republican Congress."

Italian security forces watched as pilgrims ran into St. Peter's Square to get a position for the funeral of Pope John Paul II.

Twelve pallbearers with white gloves, white ties and tails then carried the coffin on their shoulders back inside for burial, after holding the coffin to face the multitude for a prolonged moment, as the great bell of St. Peter's pealed, and waves of applause swept through the audience.

A Huge Throng Gives Waves of Applause to a Beloved Pope

By IAN FISHER

VATICAN CITY, April 8 - Pope John Paul II was buried in St. Peter's Basilica today after an outdoor funeral Mass witnessed by hundreds of thousands, the important and the ordinary alike, and watched by millions more on television.

"None of us can ever forget how, in the last Easter Sunday of his life, the holy father, marked by suffering, came once more to the window of the apostolic palace and one last time gave his blessing," Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, who knew the pope for nearly three decades, said in his homily as he pointed up from St. Peter's Square to the window of the papal apartment.

"We can be sure that our beloved pope is standing today at the window of the Father's house, that he sees and blesses us," Cardinal Ratzinger added. "Yes, bless us, holy father."

The crowd, which filled St. Peter's Square and flowed down to the Tiber River, broke out into applause, in a breeze that billowed flags from around the world, caught the red hats of cardinals and flipped the pages of the book of the Gospel resting on John Paul's plain cypress coffin. Amid tight security and worry over a terror attack, helicopter rotors chopped through the sound of Latin hymns throughout the three-hour ceremony.

It was the biggest funeral for a pope in the 2,000 or so years of the office.

To the coffin's right were heads of state from more than 70 countries, an unprecedented collection of power from five continents for a papal funeral: In the second row, the first American president to attend a papal funeral, George W. Bush, sat with his wife, Laura. Prime Minister Tony Blair and Prince Charles of Britain, President Aleksander Kwasniewski of Poland, President Mohammad Khatami of Iran and President Moshe Katsav of Israel all attended, along with four kings and six queens and the United Nations secretary general, Kofi Annan.

There were also representatives from all the world's major religions.

Behind the coffin, in bright red robes, sat more than 100 cardinals - one of whom is almost certain to become pope in the coming weeks.

And on the streets, the massive pilgrimage that has swamped Rome since John Paul died last Saturday at age 84 continued in force around St. Peter's, though not in the same extraordinary numbers as during the four days his body was on display inside the basilica.

An estimated two million people filed past his corpse after it was placed on public view on Monday, and Italian officials estimated that three million or more people had made the pilgrimage to Rome to be present in some way as the little-known Polish cardinal who was elevated to pope in 1978 was finally laid to rest.

But today, with so many world leaders present and the potential for trouble high, the Italian authorities all but shut down central Rome, making it difficult to get to St. Peter's Square. Car and truck traffic was banned - as V.I.P. motorcades zipped into and then out of town - and schools and public offices were closed. Security helicopters and fighter jets flew around airspace closed to private planes.

Rather than march downtown, tens of thousands of people watched the funeral on nearly 30 huge TV displays around Rome. Italian officials said that in all, about one million people watched the service in public settings around the city. The Mass was also broadcast worldwide on television and radio.

But no amount of security or hardship could keep away from St. Peter's the most devoted, including perhaps several hundred thousand Poles who had driven to Italy, many forsaking sleep for several days and a place to stay. Red-and-white Polish flags, many topped with black ribbons of mourning, waved in huge numbers in the plaza.

"He broke Communism and he loved peace," said Tom Czuwara, 17, who had come from Warsaw, explaining why he and 50 schoolmates drove 30 hours to be at the funeral.

Kyrian Atuogo, 27, spent nearly a year's salary to come to Rome from Nigeria, and came to the funeral with a friend carrying a huge green-and-white Nigerian flag.

"He is like the president of the world," Mr. Atuogo, a civil servant, said of the pope. "He was so nice to us, so we decided to spend our money to give him our last respects."

Some carried huge banners reading in Italian: "Santo subito" - a plea to make John Paul a saint immediately.

It was, in all, a day of extraordinary spectacle and tradition, played out on the ancient streets around the Vatican, in piazzas around Rome and, above all, in St. Peter's Square, enfolded in the ellipse of Bernini's graceful colonnade, in the company of the obelisk dragged from Alexandria by the Emperor Caligula and a dome designed by Michelangelo.

The last major papal funeral was for Pope Paul VI in August 1978, and it attracted as many as 100,000 people, a number that the Vatican said had been the largest papal funeral ever. Ninety-five nations were represented then but only a handful of heads of state. (The October 1978 funeral of John Paul I, whose papacy lasted barely a month, followed the same protocol as the rituals for Paul and John Paul II, but because it had been such a brief papacy was on a far more modest scale.)

The funeral for John Paul II - who had himself traveled to 129 countries as pope - was of a different order, in size, in the guest list from many of the countries he had visited, in the outpouring of affection, even among those who differed with him on many issues.

"He followed doctrine too much," Francesca Tatoli, 20, a student, who nonetheless traveled enthusiastically from the southern Italian city of Bari to attend the funeral. She said she disagreed strongly with John Paul's condemnation of contraception, because she believes condoms help fight the spread of AIDS.

"At the same time, he was a good man," she added, "and that's why all these people are here."

In fact, the funeral itself - with its many guests who normally have much to argue about among themselves - stood as a distinctive testament to John Paul: that people around the world found things in him and his long and eventful pontificate to admire, and, perhaps especially in death, they were willing to overlook what they disagreed with.

Without modifying church doctrine on Jesus as the Christ, the only true mediator of salvation, John Paul reached out like no other pope to Jews and Muslims - an effort attested to today by the number and diversity of political and religious leaders who came to his funeral, including, for example, dignitaries from Israel and Saudi Arabia alike.

John Paul's views on abortion and the sanctity of human life resonated with President Bush's conservative politics, even if the pope's outspoken opposition to capital punishment and both American-led wars in Iraq did not. And his forceful stance on Iraq helped his standing among Muslims.

Many Italians, like liberal Catholics in the United States and elsewhere, were attracted by his warmth and concern about poverty and social justice, even if they ignored his teaching on issues like contraception, divorce or abortion.

The guest list today also reflected several problems for the church: the Russian president, Vladimir Putin, did not attend, nor did any top patriarchs of the Russian Orthodox Church, which has ongoing conflicts with the Roman church.

China did not sent a delegation because the Vatican has no official ties with the state-sponsored Catholic church there.

Although John Paul was the most traveled pope in history, he never got to fulfill his expressed wish to visit Russia and China.

In his homily today, Cardinal Ratzinger, 77, sketched out the life of John Paul, saying that the key to understanding him was the words Christ spoke to Peter after his resurrection: "Follow me." He spoke of John Paul's loss of his mother at a young age; his working in a chemical plant in Poland; his love as a young man of philosophy, theology and poetry; his pastoral work as a priest.

But the homily focused more tightly on what John Paul II had accomplished as pope in 26 years. And Cardinal Ratzinger, a conservative expected to play a major role in selecting the next pope, said it was the pope's charisma as well as his doctrinal clarity that gave preaching the Gospels "a new vitality, a new urgency."

"He roused us from a lethargic faith, from the sleep of the disciples of both yesterday and today," he said.

The cardinal also spoke of John Paul's illness and age, repeating what many in the Vatican had said as the pope's health, and in the end his voice, failed: that in his last years, his papacy stood as an important symbol of dignity in suffering.

"The pope suffered," he said, "and loved in communion with Christ, and that is why the message of his suffering and his silence proved so eloquent and so fruitful."

For all that was unprecedented about John Paul's funeral, the basics followed centuries of Vatican tradition. It was a Mass, if one that alternated among 10 languages, and so there were no other speakers or testimonials apart from Cardinal Ratzinger's homily.

This morning, as guests gathered for the funeral, John Paul's body was sprinkled with holy water and his face was covered with a white veil. He was sealed in a cypress coffin along with some Vatican coins, then carried out of the basilica by 12 pallbearers dressed in black.

The crowd erupted in applause when the coffin - marked with a cross and an M for the Virgin Mary - came out into the sun and was placed at the top of the stairs.

After the mass, the coffin was carried into the grottoes beneath the basilica, built over the spot where tradition holds is the tomb St. Peter, who brought Christianity to Rome. There, among the bodies of more than 70 of the 264 popes, the Vatican camerlengo, or chamberlain, Cardinal Eduardo Martinez-Somalo, who administers the business of the church until a new pope is chosen, presided over a ceremony in which the cypress coffin was placed inside a zinc coffin, which was then closed inside an oak casket.

In his last testament, made public on Thursday, John Paul requested that he be buried in the earth, not interred above ground. He was buried in the spot that had held the body of Pope John XXIII, which was moved to a sepulcher inside the basilica in 2001.

But before the coffin was taken to the grottoes, the pallbearers lifted it up off the basilica steps, then, carefully turning around, held it out to face the tens of thousands of pilgrims in the crowd for a prolonged moment. The bell of St. Peter's tolled. Waves of applause swept through the people in the crowd, many of them weeping.

"I knew the ceremony today would be majestic, but I didn't realize how moved I would be by the service itself," President Bush told reporters on Air Force One as he flew home. "Today's ceremony, I bet you, was a reaffirmation for millions."

Jason Horowitz and Elisabetta Povoledo contributed reporting for this article.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top

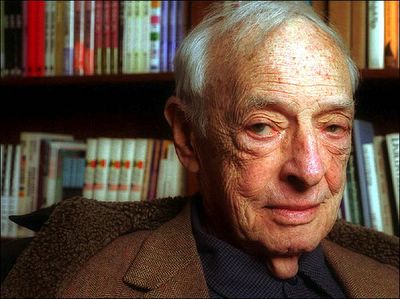

Saul Bellow, creator of larger-than-life fictional characters, in 2001.

April 6, 2005

Saul Bellow, Who Breathed Life Into American Novel, Dies at 89

By MEL GUSSOW and CHARLES McGRATH

Saul Bellow, the Nobel laureate and self-proclaimed historian of society whose fictional heroes - and whose scathing, unrelenting and darkly comic examination of their struggle for meaning - gave new immediacy to the American novel in the second half of the 20th century, died yesterday at his home in Brookline, Mass. He was 89.

His death was announced by Walter Pozen, Mr. Bellow's lawyer and a longtime friend.

"I cannot exceed what I see," Mr. Bellow said. "I am bound, in other words, as the historian is bound by the period he writes about, by the situation I live in." But his was a history of a particular and idiosyncratic sort.

The center of his fictional universe was Chicago, where he grew up and spent most of his life, and which he made into the first city of American letters. Many of his works are set there, and almost all of them have a Midwestern earthiness and brashness. Like their creator, Mr. Bellow's heroes were all head and all body both. They tended to be dreamers, questers or bookish intellectuals, but they lived in a lovingly depicted world of cranks, con men, fast-talking salesmen and wheeler-dealers.

In novels like "The Adventures of Augie March," his breakthrough novel in 1953, "Henderson the Rain King" and "Herzog," Mr. Bellow laid a path for old-fashioned, supersized characters and equally big themes and ideas. As the English novelist Malcolm Bradbury said, "His fame, literary, intellectual, moral, lay with his big books," which were "filled with their big, clever, flowing prose, and their big, more-than-lifesize heroes - Augie Marches, Hendersons, Herzogs, Humboldts - who fought the battle for courage, intelligence, selfhood and a sense of human grandeur in the postwar age of expansive, materialist, high-towered Chicago-style American capitalism."

Mr. Bellow said that of all his characters Eugene Henderson, of "Henderson the Rain King," a quixotic violinist and pig farmer who vainly sought a higher truth and a moral purpose in life, was the one most like himself, but there were also elements of the author in the put-upon, twice-divorced but ever-hopeful Moses Herzog and in wise but embattled older figures like Artur Sammler, of "Mr. Sammler's Planet" and Albert Corde, the dean in "The Dean's December." They were all men trying to come to grips with what Corde called "the big-scale insanities of the 20th century."

At the same time, some of his novellas and stories were regarded as more finely wrought. V. S. Pritchett said, "I enjoy Saul Bellow in his spreading carnivals and wonder at his energy, but I still think he is finer in his shorter works." Pritchett considered Mr. Bellow's 1947 book "The Victim" "the best novel to come out of America - or England - for a decade" and thought that "Seize the Day," another shorter book, was "a small gray masterpiece."

All his work, long and short, was written in a distinctive, immediately recognizable style that blended high and low, colloquial and mandarin, wisecrack and aphorism, as in the introduction of the poet Humboldt at the beginning of "Humboldt's Gift": "He was a wonderful talker, a hectic nonstop monologuist and improvisator, a champion detractor. To be loused up by Humboldt was really a kind of privilege. It was like being the subject of a two-nosed portrait by Picasso, or an eviscerated chicken by Soutine."

Mr. Bellow stuck to an individualistic path, and steered clear of cliques, fads and schools of writing. He was frequently lumped together with Philip Roth and Bernard Malamud as a Jewish-American writer, but he rejected the label, saying he had no wish to be part of the "Hart, Schaffner & Marx" of American letters. In his younger days, he was loosely allied with the liberal and arty Partisan Review crowd, led by Philip Rahv and William Phillips, but he eventually broke with them saying, "They want to cook their meals over Pater's hard gemlike flame and light their cigarettes at it." He spoke his own mind, without regard for political correctness or fashion, and was often involved, at least at a literary distance, in fierce debates with feminists, black writers, postmodernists.

On multiculturalism, he was once quoted as asking: "Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus? The Proust of the Papuans?" The remark caused a furor and was taken as proof, he said, "that I was at best insensitive and at worst an elitist, a chauvinist, a reactionary and a racist - in a word, a monster." He later said the controversy was "the result of a misunderstanding that occurred (they always do occur) during an interview."

In his life as in his work, he was unpredictable. He was the most urban of writers and yet he spent much of his time at a farm in Vermont. He admired and befriended the Chicago machers - the deal-makers and real-estate men - and he dressed like one of them, in bespoke suits, Turnbull & Asser shirts and a Borsalino hat. He was a devoted, self-taught cook, as well as a gardener, a violinist and a sports fan.

He was a great admirer of, among others, John Cheever, William Faulkner, Ralph Ellison (a close friend), Cormac McCarthy, Denis Johnson, Joyce Carol Oates and James Dickey. Mr. Bellow grew up reading the Old Testament, Shakespeare and the great 19th-century Russian novelists and always looked with respect to the masters, even as he tried to recast himself in the American idiom. A scholar as well as teacher, he read deeply and quoted widely, often referring to Henry James, Marcel Proust and Gustave Flaubert. But at the same time he was apt to tell a joke coined by Henny Youngman.

While others were ready to proclaim the death of the novel, he continued to think of it as a vital form. "I never tire of reading the master novelists," he said. "Can anything as vivid as the characters in their books be dead?"

Once, with reference to Flaubert, he wrote, "I think novelists who take the bitterest view of our modern condition make the most of the art of the novel," and added, "The writer's art appears to seek a compensation for the hopelessness or meanness of existence.

"Saul Bellow was a kind of intellectual boulevardier, wearing a jaunty hat and a smile as he marched into literary battle. In spite of - or perhaps, because of - his lofty position, he was criticized more than many of his peers. In reviews his books were habitually weighed against one another. Was this one as full-bodied as "Augie March"? Where was the Bellow of old? Norman Mailer said that "Augie March," Mr. Bellow's grand bildungsroman, was unconvincing and overcooked; Elizabeth Hardwick thought that in "Henderson," he was trying too hard to be an important novelist. He was prickly but also philosophical: "Every time you're praised, there's a boot waiting for you. If you've been publishing books for 50 years or so, you're inured to misunderstanding and even abuse."

Years ago, at the Breadloaf Writers Conference in Vermont, he spent a great deal of time with Robert Frost. "I thought when I was his age," he said, "people would let me get away with murder, too. But I'm not allowed to get away with a thing." Smiling, he vowed, "My turn will come."

Taking His Success in Stride

In a long and unusually productive career, Mr. Bellow dodged many of the snares that typically entangle American writers. He didn't drink much, and though he was analyzed four times, and even spent some time in an orgone box, his mental health was as robust as his physical health. His success came neither too early nor too late, and he took it more or less in stride. He never ran out of ideas and he never stopped writing.

The Nobel Prize, which he won in 1976, was the cornerstone of a career that also included a Pulitzer Prize, three National Book Awards, a Presidential Medal and more honors than any other American writer. In contrast with some other winners, who were wary of the albatross of the Nobel, Mr. Bellow accepted it matter-of-factly. "The child in me is delighted," he said. "The adult in me is skeptical." He took the award, he said, "on an even keel," aware of "the secret humiliation" that "some of the very great writers of the century didn't get it."

This most American of writers was born in Lachine, Quebec, a poor immigrant suburb of Montreal, and named Solomon Bellow, his birthdate is listed as either June or July 10, 1915, though his lawyer, Mr. Pozen, said yesterday that Mr. Bellow customarily celebrated in June. (Immigrant Jews at that time tended to be careless about the Christian calendar, and the records are inconclusive.)

He was the last of four children, but as he was always quick to point out, the first to be born in the New World. His parents had emigrated from Russia two years before, though in Canada their luck wasn't much better. Solomon's father, Abram, failed at one enterprise after another. His mother, Liza, was deeply religious and wanted her youngest child, her favorite, to become either a rabbi or a concert violinist. But Mr. Bellow's fate was sealed, or so he later claimed, when at the age of 8 he spent six months in Ward H of the Royal Victoria Hospital, suffering from a respiratory infection and reading "Uncle Tom's Cabin" and the funny papers. It was there, he said, that he discovered his sense of destiny - his certainty that he was meant for great things.

In 1924, when their son was 9, the Bellows moved to Chicago, where the family began to prosper a little as Abram picked up work in a bakery, delivering coal, and even bootlegging. The family continued its old ways in the United States, and during his childhood, Saul was steeped in Jewish tradition.