Friday, April 08, 2005

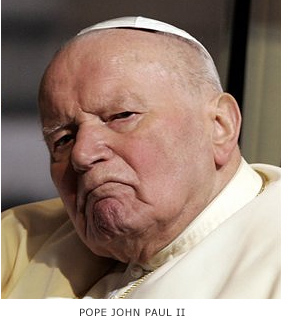

The bully pope

John Paul II ruled the Catholic Church as an autocrat, and those who crossed him often suffered greatly for it.

By Colman McCarthy

April 8, 2005 | As the secretly elected leader of a male-run, land-rich, undemocratic, hierarchic, dogmatically unyielding organization headquartered in a second-rate European country, Pope John Paul II had few, if any, worries about accountability. He ruled, accordingly, as an autocrat. Organizationally, who could challenge him? Institutionally, he projected an image of a loving shepherd endlessly traveling to distant pastures to bless the flock.

Watch out, though, if he thought you were straying. Then John Paul would "crook" you by the neck and dispatch you to a stony field where black-sheep dissidents could do penance.

He found victims early in his papacy. Enthroned only two years, the pope decided in 1980 that the Rev. Robert Drinan, a 10-year member of Congress from Massachusetts' 4th District, should get out of politics. Drinan, a Jesuit priest in the Gene McCarthy-Philip Hart wing of the Democratic Party, championed human rights and programs for the poor, and opposed Pentagon militarism. But his voting record on abortion bills wasn't strictly pro-life.

The archbishop of Boston had no problem with Drinan's being in politics. His Jesuit superiors had no problem. Paul VI, the previous pope, had no problem. Nor did the voters. But John Paul did. Drinan, who vainly asked the pope to reconsider his decree, obeyed and left Congress.

In 1980 John Paul had other troublesome priests on his hit list. Archbishop Oscar Romero was one. A former conservative who moved to the liberation-theology left when he saw up close the poor killing the poor in El Salvador, Romero was under surveillance by the Vatican. Jonathan Kwitny, a Wall Street Journal investigative reporter and author of "Man of the Century: The Life and Times of Pope John Paul II," wrote that the pope "was disturbed about Romero." Cardinals in the Vatican plotted to reassign Romero elsewhere in Latin America. Days after Romero's March 24, 1980, murder, John Paul telegrammed the president of the Salvadoran Episcopal Conference to express grief at the "sacrilegious assassination." "Not one word of praise," wrote Kwitny, was offered "for the slain archbishop." Speaking to crowds in St. Peter's Square, the pope then expressed heartfelt grief for Catholic martyrs -- in Chad, not El Salvador. Kwitny wrote: "John Paul's treatment of Archbishop Romero, and his continued treatment of Romero's memory, are an injustice like no other he has done anyone."

Another victim of papal wrath was the Rev. William Rewak, a Jesuit who served for more than 20 years as president of two colleges. In September 1998, his order appointed him president of the Jesuit School of Theology in Berkeley, Calif. Neither they nor Rewak foresaw any objections from the Vatican, which had final hiring and firing power because the school offers pontifical degrees. But papal underlings uncovered some 20-year-old writings of Rewak's on married clergy and women's ordination that differed mildly from the pope's view. It was enough to quash the pending appointment, even after Rewak left a college presidency to take the job.

John Paul was a Catholic fundamentalist. Small wonder he is being hailed by Pat Robertson, Patrick Buchanan and George W. Bush. The same ruler who bullied Drinan, Romero and Rewak -- only three of many, many -- had no objections when prelates of his own stripe dabbled in politics. During last year's U.S. presidential campaign, for instance, Bishop Michael Sheridan of Colorado Springs, Colo., thundered to his 120,000-member diocese: "Anyone who professes the Catholic faith with his lips while at the same time supporting legislation or candidates that defy God's law makes a mockery of that faith and belies his identity as a Catholic." Voters who defy church teachings "jeopardize their salvation."

Not only could John Kerry, Ted Kennedy, Patrick Leahy and other Catholic pro-choice senators spend eternity in hell but voters might burn with them.

The sorriest scandal during John Paul's long stint was his refusal to transform Roman Catholicism into a peace church. It remains polluted by the just-war theory, devised by Augustine in the fifth century and advanced by Thomas Aquinas in the 13th. The pope opposed the two U.S. invasions of Iraq, but he never renounced the notion that war can be justified. French Cardinal Jean-Louis Tauran said during the start of the second Iraq war that "the Holy See is not pacifist." The church has more than 1,500 canon laws. Not one applies to war-making.

With large numbers of American Catholic priests, nuns and lay people imprisoned for antiwar civil disobedience during the 27 years of his papacy, John Paul never once spoke out in their support. Nor did he visit any of them in prison during his seven trips to this country. Those Catholics who want membership in a peace church have a better chance with the Quakers, Mennonites or Church of the Brethren.

These old-line peace churches aren't much for dogmas, decrees, doctrines or other rubrics favored by John Paul. They favor loving their enemies, laying down their swords, sharing their wealth and doing good to those who harm them -- odd notions indeed, but ones that helped an upstart religion get footing 2,000 years back.

At best the chances are slim that the next pope, either spiritually or organizationally, will be able to undo the deep factionalism created by John Paul. Recent years have seen shelves sagging under the weight of books about the church's problems. A partial listing includes "Catholics in Crisis" by James Naughton, "The Dysfunctional Church" by Michael Crosby, "Toward a New Catholic Church" by James Carroll, "The New Anti-Catholicism" by Philip Jenkins, "Will Catholics Be Left Behind?" by Carl E. Olson, "Papal Sin" by Garry Wills, "Goodbye, Good Men" by Michael Rose, "Goodbye Father" by Richard Schoenherr, "Tomorrow's Catholics/Yesterday's Church" by Eugene Kennedy, "In Search of American Catholicism" by Jay Dolan, "A People Adrift: The Crisis of the Roman Catholic Church in America" by Peter Steinfels, "The Coming Catholic Church" by David Gibson and "Why Catholics Can't Sing" by Thomas Day.

The most prominent faction, at least at the moment, is the traditionalist one that has been summoned by the media to the airwaves and Op-Eds, there to hail the late pope as having been the fearless defender of all the rules that make The One True Church still true and still one. This faction, ever rankled at what Pope John XXIII wrought with the Second Vatican Council of the early 1960s -- every loony idea from altar girls to the handshake of peace at Mass -- saw in John Paul a no-nonsense leader. They cheered him for not yielding on the below-the-waist issues: artificial birth control, abortion, homosexuality, gay marriage. The traditionalists tend to be both theologically and politically conservative, with Antonin Scalia, Rick Santorum, Patrick Buchanan, William Bennett, Sean Hannity, Robert Novak, William F. Buckley, Phyllis Schlafly and Mel Gibson side by side in the pews.

The spiritual Catholics are those who see the papacy as irrelevant to their lives. When they pray, it isn't the prayer of asking, as though God, or Mary hailed by rote, dispensed favors, but the prayer of cooperation: Cooperate with the gifts you've been given and use them to become someone who is other-centered, not self-centered. If anyone speaks for them, it may be Leo Tolstoy in "The Kingdom of God Is Within You": "Christ could certainly not have established the Church. That is, the institution we now call by that name, for nothing resembling our present conception of the Church -- with its sacraments, the hierarchy, and especially its claim to infallibility -- is to be found in Christ's words or in the conception of the men of his time."

The pragmatic Catholics stay grounded in early church Christianity, when it was the works of mercy and rescue that kept the community together and when people practiced communism -- the pure communism of the commune. The lines from the Acts of Apostles speak to them: "All believers were together and had all things in common. And those who had possessions sold them and divided to each person according to need: Not one of them spoke of the property he possessed as his own."

These are the Catholic Worker Catholics, those who carry on the labors of Dorothy Day, who opened not homeless shelters but houses of hospitality. More than 100 of these houses can be found today, 25 years after Day's death, in both large cities and rural farming towns. Pragmatic Catholics remain loyal to the Christ described by Phillips Brooks in 1883: "In the best sense of the word, Jesus was a radical: His religion has so long been identified with conservatism that it is almost startling sometimes to remember that all the conservatives of his own times were against him, that it was the young, free, restless, sanguine, progressive part of the people who flocked to him."

Better than anyone, pragmatic Catholics understand the long-standing quip "Jesus came preaching the Gospel and ended up with the church."

John Paul, the traveling man, was helpless to keep American Catholics in line, however hard he tried. Who else did he have in mind in his railings against consumerism and hedonism? Had he stopped fuming about the rebellious Americans, he might have noticed that, with some millions attending Mass regularly in 19,000 parishes and giving more than $7 billion annually to the Catholic Church, the United States has the flock with the strongest faith in the developed world. David Gibson, a Protestant-born journalist who once worked for Vatican Radio, wrote accurately: American Catholics "are the most religiously observant Catholics in modern-day Christendom, attending church and supporting the pope to a degree that has no parallel in the industrialized world."

Someone might want to clue in the new pope.

About the writer

Colman McCarthy, a former Washington Post columnist, directs the Center for Teaching Peace in Washington. His most recent book is "I'd Rather Teach Peace."