Monday, April 18, 2005

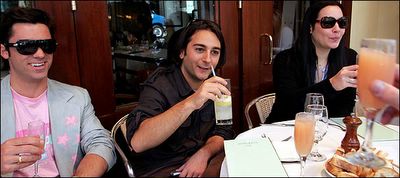

Hiroko Masuike for The New York Times

Robert Dimin, center, at Downtown Cipriani with two friends.

Here's to the Loafers Who Lunch

By ERIKA KINETZ

NEW YORK is a city of professionals and predawn discipline, an empire meant to be conquered not by wanderers but by the lusty achievement of the hyperemployed. Languorous weekday afternoons are the province of those deemed to be lacking in power.

Still, a fair portion of the city's employable population can be found, midweek, far from any office, whiling away the hours in restaurants and cafes. Unlike the corps of freelance writers with their laptops, these loiterers do not appear to be engaged in any income-producing work. Call them flâneurs, if you want to romanticize them with a French name. Some are princes of leisure, who clearly have never learned that a bank account may approach zero. Others are conscientious objectors to the rat race, who have decided that their personal freedom is worth more than the compromises that might gain you a flat-screen TV.

All of them - superrich, rich or merely upper middle class - have somehow inoculated themselves against the fiscal anxiety that drives most unemployed people to try to get a job. And they have enough disposable income to afford the minimum entry (a cup of coffee) into one of the precious places that allows low-revenue loafing.

Scattered throughout this alternative ecosystem of cafes, these people off the city grid appear to be upstanding folks with open wallets and nice footwear. But who are they? Why are they not working? And how on earth can they afford those shoes?

Downtown Cipriani

3:30 p.m. on a Wednesday The outside tables at Downtown Cipriani, on West Broadway in SoHo, were packed. Robert Dimin, an artist; Justin Melnick, a young entrepreneur; and Nicole Trunfio, a model, sat inside, around a bottle of Acqua Panna ($9) and lemonades (at $5.50 each).

Mr. Dimin wore a black baseball cap with an orange Princeton "P" pulled low over his forehead. "It's the only time to come here," he said. "Weekdays, when everyone else is working."

Ms. Trunfio got up to leave, and Mr. Melnick walked her out. They stood by his black Vespa, which has custom black matte rims, racing tires and a pipe that makes it sound like a Harley.

"Tomorrow is my birthday," Mr. Dimin said. "I turn 25. That's old." He swore he had nothing fabulous planned, just a private party at Lotus.

"I view myself as a downtowner," said Mr. Dimin, who grew up on the Upper East Side but now lives in Princeton. He said he had studied photography at Parsons but did not graduate. His fiancée, Elizabeth Kessler, is working toward a Ph.D. in archaeology at Princeton University, and he is not, at present, employed.

"I only want to make my own projects," he said. "I get yelled at every day by my family: 'Get a job. Go work for The A.P. Use your skills.' I can't. I have to do it my way."

He was wearing a black Burberry piqué shirt and striking orange Nikes. How could an idealist afford such stuff? "My $150 Nikes that should have cost $35?" Mr. Dimin said. "A lot of gifts. And my art sells for a lot of money."

Mr. Dimin's work, shown at CVZ Contemporary, includes photographs of nubile young women and an American flag fashioned of gray-and-blue fatigued cloth - much like the material of Mr. Dimin's baggy shorts - and stripes of the same thin Prada red that graces his beat-up wallet.

"I don't like money," Mr. Dimin insisted. "I'm not rich like a lot of people I know, like the 'Born Rich' movie. That's an entirely different ballgame. I'm the poorest kid of the rich kids."

Mr. Melnick, 24, came back inside and put an NTB herbal cigarette in his mouth, but didn't light it. "I'm quitting," he said.

Mr. Melnick, who said he dropped out of the University of Denver to help open a restaurant, explained that he split his time among New York, Los Angeles and Paris, running a nightclub and restaurant consultancy. He is also developing a line of surfer clothing. "For me the most depressing thing would be to make $10 million and have it be a Von Dutch," he said, referring to a popular clothing line.

He gazed at a photo of the 25-foot climbing wall at his old high school, the White Mountain School, in New Hampshire. "I wanted to expand the climbing program," he said. "So I raised the 15 grand it cost to build it." When pressed for details, Mr. Melnick explained, "The way my father looked at it was as a tax write-off." (School officials said that Mr. Melnick's father contributed $9,000; they raised the rest.)

The bill for the lemonades, which numbered about 10, was left on the table unexamined. Mr. Melnick simply announced, "I'm buying."

Doma

3:00 p.m. on a Friday Doma Cafe and Gallery, on Perry Street, was packed. Lee Bob Black, 31, moved through the place like a prince in his court. He seemed to know a quarter of the 20 people in the cafe.

He settled briefly by the window to discuss weekend plans with Edwin John Wintle, 43, a former lawyer and author of the coming memoir "Breakfast With Tiffany." "I wrote a good portion of my first book here," said Mr. Wintle, who works part-time. "If I don't sell another book, I'll be poor in less than six months."

"I'm just an unpublished writer," Mr. Black said. "I made a bunch of money at Morgan Stanley, and I haven't worked in a year." He said his first literary effort had been rejected by 60 agents. He spent only $1.63 on coffee that afternoon, and his black Skechers looked worn beyond their four months. "I don't have expensive tastes," he said.

Nearby, at a large wooden table, sat Brian Moore, 35. To look on him is to think "wage earner." Formerly a compensation analyst at Genentech in San Francisco, Mr. Moore had moved to New York seven months earlier to be with his fiancée, a resident at St. Vincent's Hospital.

Tired, he said, of PowerPoint and e-mail, he decided to study for a commercial pilot's license, and he spent most of the afternoon hunched over a training manual.

Waywardness does not sit easily. "It's a little unnerving," he said, referring to his slightly adrift afternoons. "I've tended to seek steady pay and security. Now I'm going off on an adventure. There are days when I think, 'What am I doing?' Other days I think, 'You only have one life to live.' "

He's living, in part, off his Genentech stock, but he said he was at a point at which he had to differentiate needs from wants. A flat-panel television? Definitely a want.

A friend at an investment bank had offered to help find him a job at her company, Mr. Moore said, but he said he cannot conceive of it. "I'd have to get a $10,000 signing bonus just for the wardrobe," he said.

Via Quadronno

3:45 p.m. on a Friday The small tables at Via Quadronno were packed. Paolo Della Puppa, an owner of the restaurant, on East 73rd Street, sat in back, discoursing on the origins of the European cafe and the European coffee, a trajectory that touched on Turks, Yemenis and the Habsburg dynasty.

Mr. Della Puppa is Italian, and many of his patrons share his European roots. "American rich, you are a C.E.O., you have no time," he said. "Italian rich, they live like rich people. They go to work at noon. They enjoy life."

Via Quadronno is host to a rotating assortment of diplomats, guests of the nearby Carlyle hotel, private-school moms, members of the Agnelli family and the occasional teenager possessed of a black American Express card.

Yet Sue Ventura and her husband, Lou, are also regulars. Mrs. Ventura, a student at the New York School of Interior Design, did not enter the world of the $4 afternoon cappuccino until middle age. In 1994 - in honor of her 40th birthday - she quit her job as a bond trader after 15 years on Wall Street. "My liberation," she said, beaming. Her husband still works as a senior managing director at Bear Stearns, though he joins her there after work most days.

Now, instead of eating at her desk, she practices Italian with the staff at Via Quadronno. But stepping out of a life of hyperproductivity, she says, where one's value is as quantifiable as one's trading powers, was as unsettling as it was glorious.

She has reconciled herself to slowness. "Life is fleeting," she said. "You've got to step back every once in a while."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top

Stephen Savage

OP-ED CONTRIBUTOR

Holy Rollers and Papal Perfectas

By FRANK DELANEY

MY mother voiced many moral dismissals in her time, the chief of which ran, "That fellow - he'd bet on two flies going up a wall!" Oh, what in Heaven can she be thinking now, from her ringside seat up there near God, as she watches Paddy Power, Ireland's best-known bookie, run the odds on the papal conclave that begins in the Sistine Chapel today? "Simony," I imagine she'd cry, referring to that rarely discussed sin of "traffic in sacred things." And, in her encyclopedic way, she would then cite a 17th-century papal bull that explicitly forbade betting on the transition between pontiffs.

But Mother would evince no surprise; nor, I expect, does anyone in Ireland, a country where, often, to bet is to live.

First a piece of Irish wisdom: you should always listen to a bookie. For they have a saying, "Money tells a good story," and somewhere in their odds is a kind of science-fiction existentialism that decrees that we, the people, know everything. In other words, betting patterns often make for good, unconscious soothsaying.

Therefore, if the smart money is telling it right, the next pope will be one of the following three men: Joseph Ratzinger, the 77-year-old German who is dean of the College of Cardinals; Carlo Martini, 78, the former archbishop of Milan, perhaps the world's most powerful Roman Catholic archdiocese; and, on their heels, Jean-Marie Lustiger, the 78-year-old former archbishop of Paris who, Mr. Power's helpful Web site says (with questionable historical accuracy), would be "the first converted Jew ever elevated to the papacy."

These three eminences have been leading the field for days, with odds quoted along a range from 3-1 to 7-2. Another early favorite, Cardinal Francis Arinze of Nigeria, has at last glance dropped back to 8-1; and the money moved to Cardinal Cláudio Hummes from Brazil - two weeks ago he was 12-1, but now one can get you only eight on the Latin American.

So, how did the favorites race to the front? Usually a bookie takes his measure from a combination of recent performance, street smarts and insider information. So far, much of the $200,000 or so Mr. Power has received has gone on Cardinal Ratzinger. His strong showing comes, it seems, from an Internet rumor that the German's kingmakers had already, even in the last days of the ailing John Paul II, collared half of the votes of the 117-member college. Stay with that word "rumor"; that may be as solid as it gets because, for another favorite, Cardinal Lustiger, we need a jab of true faith.

This good man surged from long shot to front-runner in a matter of days. The impetus? Well, ahem, it started some time back, in 1139 to be exact, when an Irish saint called Malachy received (in a vision, naturally) the identities of all future popes. And here we have a deeper, more worrying problem. St. Malachy prophesied that only two popes would preside after the pontiff whom his adherents recognize as John Paul II, and that the second-to-last would be born a Jew. "Smart" money? Hmm.

Growing up in Ireland, I lived among relics and racehorses, in farms where the limestone bedrock made for beautiful monastery walls and, deposited as calcium in the water, great equine bones. I profoundly understand this bizarre combination of sacred and profane. As a child I watched opportunistic men peddle cigarettes and ice cream where people flocked to see statues that bled, smiled or trembled in local miracles. And every parish priest worth his salt had a horse or a piece of a horse. Today, it seems, all those forces have fused in me to the point where I can scarcely resist a stake.

Yet, once a Catholic always a Catholic, and before I step up and put my money down I have to recognize that I'm up against unseen forces. Meaning, how can I consider anything as a safe bet when divine intervention remains a factor in the conclave?

Still, were the lure of gambling to overpower the fear of God in me (and, God knows, it might), I'd have a crack at a few of the outsiders. For instance, at 25-1, Angelo Scola is an interesting bet; he's the patriarch of Venice, speaks several languages (including English) and is only 63 years old. And have a look at the Argentine, Jorge Mario Bergoglio, also showing strongly at 12-1. And though he is not even given odds (in Irish racing parlance, a "rank outsider"), Cardinal Justin Rigali of Philadelphia is a very effective Vatican operator and truly worth a piece of my money; after all, in 1977 Karol Wojtyla was such a long shot he had scarcely left the paddock before the others were round the first bend.

In the end, of course, those who want to play Paddy Power's game will have to be careful as to whom they openly fancy; as every Vatican watcher knows, "He who goes in a pope comes out a cardinal."

Obviously, mutterings of "sacrilege" and "irreverence" have been heard in old Hibernia. (Even though there may be a fine point of canon law as to whether Mr. Power is actually making bets or merely taking them.) Have no truck with such killing of joy, I say - God may not be a gambler, but isn't that because he never felt the need? And, anyway, who invented forgiveness for human frailty? He hasn't yet struck down, so far as I can tell, any of these holy rollers.

But if you still feel it's sacrilegious to bet on these contenders, you can have a theologically safer flutter on the name of the next pope: Benedict (3-1), John Paul (7-2), Pius (6-1), Peter (8-1) and John (10-1) are among the favorites. An 80-1 outsider of outsiders is the name Damian (which would give shudders, I guess, to moviegoers who remember "The Omen"). Or you can bet on the number of days this conclave will take - one day (14-1), three days (5-4) or six days or more at 7-1.

THERE may be more to come. On Saturday, in Rome, Mr. Power set up his stall to shout the odds across St. Peter's Square. Soon enough, some men, whom he described to me in a phone conversation as "the undercover police," moved him on; he was, he said, "minutes away from the slammer." He's been taking hundreds of bets, though, from the Italians, and waiting to see how much he eventually will have to pay out on what he calls "holy smoke." Even my mother would, I think, smile at that coinage - but she might not let God see her.

Frank Delaney is the author, most recently, of "Ireland: A Novel."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top

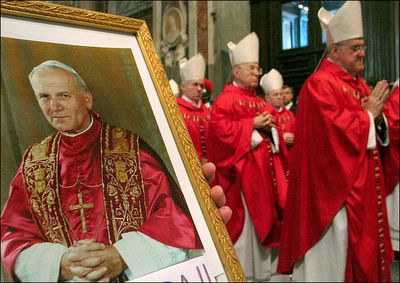

Gregorio Borgia/Associated Press

Cardinals leaving St. Peter's Basilica after a Mass ending the mourning period for Pope John Paul II

Cardinals Align as Time Nears to Select Pope

By LAURIE GOODSTEIN and IAN FISHER

ROME, April 16 - There was never doubt that Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, the Vatican's hard-line defender of the faith, would have a strong hand in selecting the next pope. But in the days of prayer and politics before the conclave, which begins on Monday, he has emerged as perhaps the surprise central figure: the man who could become the 265th pope, choose him or be the one other cardinals knock from the running.

Any talk of who will become the next pope is guesswork, echoes from cardinals and their staffs sworn to silence about one of the world's most elite and secretive gatherings.

But one bit of wisdom has emerged in the Italian press as conventional: that Cardinal Ratzinger, a German close to John Paul II, has up to 50 votes among the 115 elector cardinals, or at least that is the strength his supporters claim.

That is short of the two-thirds, or 77 votes, needed in the early stages of voting. Still, he appears to command the largest and most cohesive block, and at a minimum, it seems unlikely that the next pope will be chosen without his blessing.

But interviews with more than a dozen Vatican experts and church officials suggest that forces are lining up against Cardinal Ratzinger - who, at 78, may be judged too old, too uncharismatic and, perhaps most important, too rigid to hold together a polarized church that is a billion people strong.

Some believe the church needs a more moderate man, a less authoritarian leader or one from outside of Europe.

"Ratzinger represents continuity - he was the right-hand man of the pope," said Giuseppe De Carli, head of Italian public television's Vatican bureau, who in recent years has interviewed most of 115 cardinals who will begin the secretive process of selecting the new pope on Monday.

"But the cardinals need both continuity and discontinuity," he added. "They can't create a pope that will be the photocopy of the preceding one."

Some experts say that is precisely the problem: that Cardinal Ratzinger has ambitions higher than being a photocopy of John Paul.

Based on Cardinal Ratzinger's record and pronouncements, his agenda seems clear. Inside the church, he would like to impose more doctrinal discipline, reining in priests who experiment with liturgy or seminaries that permit a broad interpretation of doctrine. Outside, he would like the church to assert itself more forcefully against the trend he sees as most threatening: globalization leading eventually to global secularization.

But some cardinals worry that it is healing, not confrontation, that the church needs. Most cardinals eligible to vote are now refusing media interviews - a consequence of the media blackout the cardinals decided to impose eight days ago. But some are talking on background to Vatican colleagues, church scholars, leaders of Catholic organizations and to Italian journalists who specialize in covering the Vatican. The New York Times spoke with several cardinals and more than a dozen people in recent contact with the cardinals. Most spoke on the condition of anonymity.

The top candidate of the forces opposing the Ratzinger bloc appears to be Dionigi Tettamanzi of Milan, who could also have a chance of peeling off a few votes from the Ratzinger camp. His profile offers a little something for each flank. A conservative moral theologian who has written on bioethics, he collaborated with John Paul on the encyclical laying out the justifications for opposing abortion, birth control and euthanasia.

In recent years, however, Cardinal Tettamanzi has began to sound off on issues of poverty and social justice. When protesters went to Genoa, Italy, for the Group of 8 summit meeting of industrialized nations in 2001, he spoke to the crowd on the evils of globalization.

Sandro Magister, a Vatican expert who writes for L'Espresso magazine, said the cardinal could unite conservatives and liberals. "He is an exponent of compromise, but a real honest conservative," Mr. Magister said.

The interviews suggest that the standard-bearer for the liberals among the anti-Ratzinger forces is, at least for the moment, the retired archbishop of Milan, Carlo Maria Martini. There is a strange sort of symmetry to the two men: both are 78-year-old scholars with stratospheric intellects who command the respect of their colleagues.

But Cardinal Martini appears to control far fewer votes. He has said he has not ruled out changes to priestly celibacy or the bans on contraception and on women serving as deacons. He has a form of Parkinson's disease and, unlike Cardinal Ratzinger, is not considered an active candidate. Experts say that while he respects Cardinal Ratzinger, Cardinal Martini does not support his vision of the church.

"Martini," said Alberto Melloni, a papal historian, "thinks that if the church does not move on in terms of doctrine, it is condemned to lose the content of Christian truth."

If the cardinals could start from scratch and order up the perfect pope, the candidate to lead the Roman Catholic Church of 2005 might look like this:

Charismatic and basically conservative. Intellectual but accessible. Speaks Italian, Spanish and English. Not too old, not too young, since the cardinals want neither a 26-year papacy like John Paul's nor a pope who will be bedridden in two or three years. A pastor, but one familiar with Vatican bureaucracy. Someone willing to let local bishops go their own way - within limits. Perhaps he would be from the third world, where the church is growing, but he has ties to Europe and could reinvigorate the flagging faith there.

Holding this template against the men in the running gives some clues, with the caution that the candidate who comes closest does not necessarily win. Politicking will also play a major role - and at this moment the central player is indisputably Cardinal Ratzinger.

A close associate of John Paul for nearly 30 years, he has a soft voice, a shy manner and a full head of white hair. Friends say that he gets wrongly portrayed as "God's Rottweiler" and that he is actually a warm and spiritual man.

"In the last months of John Paul's papacy, Ratzinger was visible as the supporting column of the church, and so they are following him," Mr. Magister said.

Several church sources said Cardinal Ratzinger had the support of an international array of cardinals, including Francis George of Chicago; Christoph Schönborn of Austria; Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina; Camillo Ruini and Angelo Scola of Italy; and Marc Ouellet of Quebec.

But some cardinals said in interviews before this week that he might centralize power even more than John Paul, just when many cardinals are hoping for their local dioceses to have a greater say in their affairs.

Cardinal Martini's progressive bloc could not wield enough votes to block Cardinal Ratzinger. But the opposition is being joined, several Vatican watchers said, by other groups, in particular a group of Italian cardinals, who by several accounts include Angelo Sodano, John Paul's last secretary of state, and Giovanni Battista Re, who had been in charge of bishops under the late pope.

The members of the Ratzinger contingent are well aware that their candidate may lose, and so are ready to shift their votes. The most obvious backup, several experts said, is Cardinal Ruini, the vicar of Rome.

He is as a forceful figure in Italian politics, opposing rights for gays and lesbians and some forms of assisted reproduction, and supporting immigrants' rights.

But he faces the opposition of those Italian cardinals supporting Cardinal Tettamanzi, so other Ratzinger protégés could emerge.

One is Cardinal Bergoglio of Argentina, a conservative Jesuit who early in his career distanced himself from proponents of liberation theology. Born to Italian parents, he could be a bridge between Latin America and Europe.

A second is Cardinal Scola, patriarch of Venice, a scholar and a tireless pastor. He has spotless conservative credentials, softened by a grass-roots style.

Another is Cardinal Schönborn of Vienna. An aristocrat, he has often made lists of potential popes because of his intellect, language skills and conservatism, but his administrative skills may seem lacking.

The Latin American cardinals, with 18 percent of the cardinal electors, match the strength of the Italians. But they do not all share the same vision of the church's needs. Nor, it seems, are they all rooting for the home team.

Alejandro Bermúdez, the Peruvian editor in chief of ACI Prensa, a Catholic news agency in Latin America, said those prelates held no conviction that the next pope must be from Latin America. "They would not be opposed to it," he said, "but at this time it is not their priority."

Still, several Latin Americans were frequently mentioned as strong candidates: Cardinal Bergoglio; Claudio Hummes of Brazil, a progressive who moved to the right; and Oscar Andrés Rodríguez Maradiaga of Honduras, a conservative on social issues.

Also mentioned were Norberto Rivera Carrera, archbishop of Mexico, who at 62 may be considered too young, and Juan Sandoval Iñíguez, 72, archbishop of Guadalajara.

With so many candidates and so much apparent division, another familiar situation is looking more and more possible.

In the last conclave in 1978, Vatican-watchers had concocted lists of potential popes 20 to 30 names long, hoping that would cover all the possibilities. But Karol Wojtyla, the cardinal from Poland who became Pope John Paul II after three days, made practically none of them.

"Do not underestimate the power of the microculture that is generated among the cardinals when they are together," said Mr. Bermúdez, the Peruvian editor. "The kind of reflections that end up influencing them are completely unpredictable."

Elisabetta Povoledo of the International Herald Tribune contributed reporting for this article.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top

James Hill for The New York Times

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger reminded the other 114 cardinals that there are absolute truths in the church, and they should choose a man who will protect them.

Cardinals Finish Preparations for Conclave

By DANIEL J. WAKIN

ROME, April 16 - The cooks and elevator operators have been sworn to secrecy. A smokestack has been placed on the Sistine Chapel's roof. And on Saturday, the cardinals who will elect Pope John Paul II's successor held their last formal meeting.

Most details have been tied up ahead of Monday's conclave, the secret gathering of the princes of the church that will end when white smoke emerges to signal that they have chosen a new pope.

Saturday was also the end of the official nine days of mourning for John Paul that began with his funeral on April 8. And the cardinals watched as John Paul's Fisherman's Ring, a symbol of the papacy, was destroyed.

Joaquín Navarro-Valls, the Vatican spokesman, said the cardinals had conducted their final gathering Saturday morning in an atmosphere of "great familiarity."

Dr. Navarro-Valls said no individual candidates for the papacy were discussed during the meetings. But several cardinals, their aides and Vatican analysts have all said that such discussions were liberally taking place outside the meetings.

After the cardinals move into their sequestered residence during the conclave, Santa Marta, on Sunday, they will have dinner together there, the spokesman said.

Dr. Navarro-Valls said the cardinals' procession into the Sistine Chapel on Monday would be televised by the Vatican, along with their taking the oath of secrecy and obedience to the rules of papal succession.

He said Vatican security officials had ensured that there would be no leaks about the highly secretive proceedings, and hinted that measures had been taken to prevent cellphone reception. "Try testing them when you go into the Sistine Chapel," he told reporters who were later given a special tour on Saturday.

And in fact, cellphones did not work, as they usually do. A Swiss guard said a jamming device had been placed under the platform floor in the chapel.

A three-foot-high metal stove that is used to burn the ballots, with the dates of past conclaves etched on its surface, sat in the front part of the chapel. Scaffolding held the bright copper stove pipe that will emit black or white smoke to signal the election's outcome. Another device that looked like a more modern stove sat next to it and was connected to the stove pipe, apparently to speed up the movement of smoke. Two fire extinguishers stood nearby.

On Friday, workers installed a narrow smokestack on the roof to be linked to the stove pipe.

Staff members and others involved in the conclave took an oath of secrecy the same day.

They included important clerics but also priests assigned to hear the cardinals' confessions, waiters and cleaning staff, the bus drivers shuttling the cardinals between Santa Marta and the Sistine Chapel, and elevator operators who will bring the cardinals to the chapel.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top

Marco Longari/Agence France-Presse

Although the conclave could last for days, a pope could be chosen as early as Monday afternoon.

Cardinals Gather Today in Secret to Elect the Next Pope

By DANIEL J. WAKIN

ROME, April 17 - Bathed in mystery and, many believe, the Holy Spirit, the conclave to elect a new pope that opens Monday marries the highest Roman Catholic Church solemnity with one of history's longest-lived electoral experiences.

The event - which has not occurred in more than 26 years but dates back nearly a millennium - is a unique mix of pageantry and practicality, a regal balloting exercise that even a big city ward heeler might recognize.

In theory, the 115 voting cardinals are all candidates. But tradition and human nature work together to create a rough winnowing process.

"They try to be inspired by the will of God in prayer," said Ambrogio M. Piazzoni, a conclave historian who works in the Vatican library. "In the end, it's the cardinals who say who will be the next pope."

The first vote - which could occur as early as Monday night - is likely to be showdown time, Vatican analysts said.

Historically, before being sequestered, the cardinals have already coalesced around several favorites, thanks to formal daily meetings and informal encounters in the days after the pope's death. The strength of support becomes clear in that first vote.

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger, 78, one of the pope's closest aides and a doctrinal conservative, appeared to have the largest bloc, and Italian analysts said his opponents might first vote for Cardinal Carlo Maria Martini, 78, the more progressive former Milan archbishop and a much-respected figure. But he is considered too infirm to be pope; the votes would serve as a show of force and might, in later rounds, be shifted to a more viable candidate. Cardinal Ratzinger, too, might channel his votes to someone else.

But new options could emerge Tuesday.

"After the first scrutiny, you see the way things are going," Mr. Piazzoni said. "Slowly, slowly, you arrive at a majority."

In fact, opening favorites often do not pick up enough steam during the early rounds of secret balloting. Compromise candidates emerge and power broker cardinals shift their support. Cardinals decide during meals or after-dinner strolls, and convey their preferences in quiet chats.

"You know that your vote is important, but it is one, and you feel a little dominated by the blocs," a Spanish cardinal, Vicente Enrique y Tarancón, was quoted as saying in the 1984 book "Secrets of the Vatican from Pius XII to Pope Wojtyla," by Benny Lai, a journalist who has covered the Vatican for many decades. If the conclaves of the last century are any guide, a pope should be elected by the end of the week. The longest conclave took 14 ballots, lasted five days and produced Pope Pius XI in 1922. The shortest - a day - elected Pius XII in 1939 (three ballots) and John Paul I in 1978 (three or four ballots).

It was not always that way.

The longest conclave took two years, nine months and two days. It ended with the election of Gregory X on Sept. 1, 1271. Gregory, not surprisingly, wrote new rules to speed things up. If no one was elected within three days, he decreed, rations were to be cut to one meal a day. After five more days, the cardinals would be restricted to bread and water.

The next election lasted one day. The new pope, Innocent V, lasted five months.

The wash of grandeur that accompanies the opening of a conclave obscures political maneuvering.

The day begins with a 10 a.m. open Mass for the election of the pope in St. Peter's Basilica. At 4:30 p.m., the cardinals make a procession to the Sistine Chapel, as chanters intone the litany of the saints.

They sit on curve-backed wooden chairs along a dozen long tables, six on a side. They will be able to see Michelangelo's "Last Judgment" on the west wall out of the corner of their eyes.

Specialists have swept the chapel and areas around it for bugs, as Pope John Paul II ordered.

In the chapel, Cardinal Ratzinger, as dean of the cardinals is called upon to sing the hymn "Veni, Creator Spiritus" to invoke the Holy Spirit. He says a short prayer, and the cardinals place a hand on the Gospels and swear an oath spelled out in John Paul's 1996 constitution on papal succession, "Universi Dominici Gregis," or "Shepherd of the Lord's Whole Flock." The cardinals vow to follow his rules, serve faithfully as pope if elected and keep the proceedings secret.

Archbishop Piero Marini, the master of papal liturgical ceremonies, orders, "Extra omnes," "Everyone out." Any attendants leave, and the 115 voting cardinals are left to themselves. Although there are 183 cardinals, only the 117 younger than 80 are permitted to vote and two of them are not attending the conclave for health reasons.

They then decide whether to hold a round of voting or wait until Tuesday morning. The balloting is highly ritualized, minutely detailed by the constitution, involving folded paper ballots and a walk to the altar to deposit of them into an urn.

Two scrutinizers, chosen by lot among the cardinals, each record the votes. A third reads the names aloud so the cardinals can keep their own tallies. After Monday, each day will open with a 7:30 a.m. Mass in the Vatican's Santa Marta residence, where the cardinals moved Sunday, and two rounds of voting will take place in the morning and two in the afternoon, accompanied by prayers and Bible readings.

Any notes the cardinals keep must be handed over and burned, although a permanent record of the proceedings is kept in the secret archives. Other popes allowed notes to be kept for posterity, but these cardinals are operating under rules of secrecy reinforced by John Paul II. The ballots, too, are burned, producing the smoke that emerges from the scrutinized chimney. A second stove has been added this time for smoke canisters to reinforce the signal. Bells will ring when white smoke rises, signifying a pope has been elected, another innovation. Black smoke means no pope has been chosen.

If no cardinal wins a two-thirds majority, 77 votes, after the third day, the cardinals will pause for a day for prayer and discussion, as John Paul ordered. Voting resumes for seven ballots, followed by another pause; then seven more and another pause; then seven more. If there is still no pope, John Paul said, the cardinals may resort to a simple majority, or 58. Such a turn would come around May 1.

The method has evolved over the course of the church's history. In the early centuries, the people of Rome, warring aristocratic families and emperors chose popes. St. Fabian was selected in 236, the legend goes, because a dove landed on his head.

The job was given exclusively to the cardinals in 1179, with the two-thirds majority rule. Irregularities abounded. Julius II become pope in 1503 by bribing fellow cardinals.

Now, the process has grown to resemble local Italian elections, wrote Orazio La Rocca, a journalist who covers the Vatican, in his book "The Conclave." It can be seen in the way the ballots are counted and the move to a second round runoff if necessary. In fact, the constitution was partly the work of an Italian cardinal, Mario Francesco Pompedda, a Vatican jurist.

The election of John Paul II, whose death on April 2 set in motion this papal transition, offers hints of what may come in the next few days.

That conclave started pitting Giuseppe Siri, the conservative archbishop of Genoa, against Giovanni Benelli, the more progressive archbishop of Florence and protégé of Pope Paul VI.

In the first round, each received roughly 30 votes, according to "Heirs of the Fisherman," a book about papal succession by John-Peter Pham, a former Vatican diplomat. They seesawed until Cardinal Siri reached 70 votes, just 5 shy of white smoke.

But he gave a newspaper interview the day before the conclave and made comments that were viewed as critical of John Paul I, Vatican II and sharing power with the bishops.

The interview was supposed to have been embargoed until the cardinals were sequestered, but the article came out the day the conclave started. The cardinals received copies. Cardinal Benelli was blamed for orchestrating the early publication and distributing the copies.

Less well known are indications, reported by Mr. Lai in "Secrets of the Vatican," that Cardinal Siri was told that if he would consider Cardinal Benelli as his secretary of state, he would receive enough votes. But the Genovese cardinal refused, and the stalemate continued.

That opened the way to Karol Wojtyla of Poland. The next morning, he won 11 votes, and his supporters pressed the case for him over coffee. The cardinals were under pressure to act quickly to show the world they were unified. That afternoon, Cardinal Wojtyla found himself with an overwhelming majority.

Chroniclers suggest one crucial factor was the support of German-speaking cardinals, led by Franz König of Austria, and the Polish-American John Krol. But the Italian deadlock played an undeniable role. "God was served by the malignity of men and the division among the Italians," Mr. Lai quoted Cardinal Enrique y Tarancón as saying.

The cardinals will be operating in a cocoon of secrecy and rigid principles laid down by John Paul. They are forbidden access to television, radio, publications, the telephone and mail. They are not permitted to exchange messages with the outside world, which presumably includes e-mail. Any attempt by a cardinal to introduce outside interference is punishable by automatic excommunication. The cardinals are not to make deals to vote for a candidate in exchange for a concession. Friendships or animosities, news media pressure and a search for popularity should have no influence.

Just about the only advice John Paul gave on how to choose the pope was this: pick the person who is "most suited to govern the universal church in a fruitful and beneficial way." And he urged the one selected not to flee the burden.

Historians, in fact, cite a few cases of deep reluctance.

When Cardinal Giuseppe Sarto, about to become Pius X in 1903, was asked the traditional question of whether he would accept the papacy, several accounts describe him as tearful and almost desperate.

"Oh, my dear mamma, my good mamma!" Mr. La Rocca quoted him as saying. "I accept, on the cross."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top

Vatican TV via AFP ? Getty Images

A picture taken on Telepace 18 April 2005 shows a senior Vatican official closing the doors of the Sistine Chapel, formally starting the first conclave of the third millennium in which 115 cardinals will choose the next pope..

Black Smoke Emerges, Signaling No New Pope Today

By DANIEL J. WAKIN

and IAN FISHER

ROME, April 18 - Black smoke rose from the chimney of the Sistine Chapel this evening as cardinals of the Roman Catholic Church signaled that they had voted inconclusively in their first attempt to elect a successor to Pope John Paul II.

For a few moment, the first wisps of smoke looked white to the many spectators drawn to St. Peter's Square in the Vatican and hopes rose that a pope had already been chosen. Soon, however, the smoke turned decisively black as it wafted from a stovepipe chimney, blowing in the winds at dusk.

The cardinals are to vote again at their conclave on Tuesday.

Earlier today, the cardinals retreated behind the heavy wooden doors of the Sistine Chapeland began the tradition-laden and secret ceremonies to elect one of their number the 265th pope.

In solemn procession, walking slowly in pairs, they proceeded into the chapel as a choir chanted the Litany of Saints, passing through a pair of Swiss guards in full regalia. After taking their seats behind long tables, the cardinals were read an oath of secrecy and obedience by their dean, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger. Their birettas, red hats that symbolize the power of their offices, sat on the tables in front of them.

Then they lined up and one by one put their hand on the Gospel and swore to obey. The entire pageant was televised live, a first in conclave history and in keeping with the tradition of John Paul II, who used television throughout his papacy to promote the faith. Even in death, his image was broadcast as he lay in state inside St. Peter's Basilica.

"Extra omnes!" cried Piero Marini, the master of papal liturgical ceremonies - or "Everyone out!" He and a theologian chosen to deliver an inspirational message remained. The rules called for them to leave after the address. At that point, the cardinals were to decide whether to hold a first round of voting tonight or not.

Earlier in the day, they heard another message. Cardinal Ratzinger, who will be a powerful force in the conclave, took the occasion of a morning Mass dedicated to the election to issue denounce anyone who would stray from traditional Catholic doctrine.

The 114 other cardinals sat in quarter-circles in front of him. It was the last public rite before the conclave.

"A dictatorship of relativism is being built that recognizes nothing as definite," Cardinal Ratzinger said, "and which leaves as the ultimate measure only one's ego and desires."

For 25 years, Cardinal Ratzinger served as John Paul's theological right hand - and watchdog - as prefect of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith.

In his writings and public statements, Cardinal Ratzinger has often sought to uphold the primacy of Catholicism, saying no other religion offered a path to salvation. "Relativism," he has said, implies - wrongly - that other faiths are equally valid. The idea was strongly expressed in a document the congregation issued in 2000, Dominus Iesus, which provoked angry responses from other religious leaders.

In his homily today, Cardinal Ratzinger said that Christians were tossed on the waves of Marxism, liberalism and even "libertinism;" of radical individualism, atheism and vague mysticism. He also decried the creation of "sects" and how people are seduced into them, using a term church leaders often employ to refer to Protestant evangelical movements.

"Having a clear faith, according to the Credo of the Church, is often labeled as fundamentalism," he said. "Yet relativism, that is, letting oneself being carried 'here and there by any wind of doctrine,' appears as the sole attitude good enough for modern times."

Many of the cardinals, draped in bright-red vestments and wearing white mitres, watched intently as Cardinal Ratzinger spoke on a platform below Bernini's bronze baldacchino. Several others among them - two thirds of the cardinals voting for pope are septuagenarians - appeared to doze.

Cardinal Ratzinger, 78, spoke Italian in heavily accented German, his voice creaky at times and interrupted by coughs. Several church officials said he had been suffering from a cold.

The cardinal has emerged as a front-runner in the election for the next pope, or at least the reference point for a bloc of support generally oriented toward a more conservative position. He has been a major force among the cardinals since John Paul's death on April 2, celebrating the funeral Mass and leading the cardinals' regular daily meetings.

Commentators agreed that while the cardinal had been saying similar things for decades, hearing them expressed, and so sharply at that, just before the conclave was unexpected. But there were different interpretations of his intent.

At the funeral, the cardinal showed his pastoral side, said John-Peter Pham, a former Vatican diplomat and author of a book about papal succession.

At the Mass today, "he's giving evidence that he also has, if you will, the 'vision thing,' that he has definite ideas of where the natural progression of John Paul's theological legacy is," Mr. Pham said. "Whether that's a campaign statement or requirement of what the next guy must have - that remains to be seen."

The message is that John Paul's goals must be maintained, he said. "Either as a candidate or a grand elector, he's definitely in a very strong position, and he wouldn't have made this statement if he was standing alone," Mr. Pham said.

Alberto Monticone, a professor of modern history at Lumsa Catholic University in Rome, called the comments "a very clear indication of what in his view the attitude of the next pope should be - an attitude of struggle against these evils of the world."

It was likely that most of the cardinals were well familiar with Cardinal Ratzinger's thinking, and his belief that the church's first priority should be to shore up the doctrinal walls.

"It's very honest," said the Rev. Gerald O'Collins, a theologian at the Gregorian Pontifical Univesity in Rome. "That's what he thinks."

"Some of the cardinals would not agree with his summation," he said. "Other things like war and peace and hunger are high on the agenda of other cardinals."

After attending the Mass, the Rev. Raymond J. de Souza, chaplain at Newman House at Queens University in Kingston, Ontario, said that Cardinal Ratzinger's homily was an "exhortation" to the cardinals to go into the conclave keeping in mind that the primary responsibility of a pope is to preserve the faith passed on from the apostles and not to dilute or experiment with it.

"If the faith is strong, then the church can take on these other issues," said Mr. de Souza, who writes a syndicated column.

Prof. Hans Küng, a theologian at the University of Tubingen, who has tangled with Cardinal Ratzinger, said he heard similar views many years ago from him. "His ideology is a medieval, anti-Reformation, anti-modern paradigm of the church and the papacy," he said.

The mourning that followed John Paul's death seemed fully lifted today, amid an air of expectation in the church and St. Peter's square. In contrast with the solemnity of the funeral rites, the Mass today was open to tourists, whose babies cried and cameras flashed at this latest chapter in two millenniums of history.

Four large screens were set up in St. Peter's Square to broadcast the Mass live. Crowds of tourists, clergy, Vatican officials and nuns gazed up at the cardinals projected on the screens. Some said they were praying for them.

Brother Felix, who has come from Germany to Rome to study, said that while the conclave was indeed a political process, "the whole election is a prayer," explaining, "They pray that their human voting is led from the Holy Spirit."

Already, the crimson curtain has been hung on the central balcony of the basilica facing St. Peter's for the new pope's traditional first appearance before the crowds.

About an hour before Mass, the cardinals left St. Martha's residence, a hotel of sorts on the Vatican grounds built by John Paul for conclaves.

They made the 100-yard walk to the basilica, strolling mostly in groups of two and three, including two cardinals mentioned as possible popes: Jorge Mario Bergoglio of Argentina and Tarcisio Bertone of Italy. Roger Mahony of Los Angeles shared a chipper greeting with reporters. A French cardinal, Paul Poupard, chatted briefly with the French press.

With the conclave under way, all the cardinals will now remain cut off from all outside contact.

After the Mass, the congregation of priests, nuns, pilgrims and a scattering of tourists applauded as the cardinals walked in procession out of the basilica, the applause rising, it seemed, as favored papal candidates passed. But the loudest applause was for Cardinal Ratzinger as he pulled up the procession's tail - so enthusiastic that he gave a big smile to recognize it.

Laurie Goodstein contributed reporting from Rome for this article.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top

Danilo Schiavella/EPA

From left, Cardinals Giovanni Battista Re, Angelo Sodano and Joseph Ratzinger celebrated a Mass at St. Peter's Basilica this morning

Even Cardinals Are Prone to Peer Pressure

By HENRY FOUNTAIN

TOMORROW, 115 of the most powerful Roman Catholic officials in the world will be locked into the Vatican, where they will live and breathe church issues, and personalities, 24 hours a day until they elect a successor to Pope John Paul II.

The conclave of cardinals will take place amid extraordinary secrecy and seclusion. No phone calls, letters or e-mail messages will be allowed - and certainly no "Survivor"-style camera crews asking the cardinals to explain their vote during each round of balloting.

These events are so secret that it is difficult for anyone outside the college of cardinals itself to fully know what goes on, at least for years afterward. One expert in organizational behavior described a papal conclave as "utterly opaque" and compared it, jokingly, to trying to understand the government of North Korea.

Although this is no ordinary deliberative body - and the cardinals no ordinary citizens - those who study group dynamics say that when the conclave begins, some ordinary things are likely to occur.

Being a cardinal "doesn't exempt you from basic psychological things happening," said Richard Moreland, a psychology professor at the University of Pittsburgh. And one basic psychological thing that happens in groups is that some members accede to the desires of others.

"Conformity is a big thing," Dr. Moreland said. There are two types: informational conformity, where one person believes others know best, and normative conformity, where fear of rejection or of loss of status is the driving force.

Some cardinals already have greater leadership roles; they travel and meet with other high church officials regularly. So informational conformity may play a role. Because well-connected cardinals may be perceived as having better access to information, they may hold sway over colleagues who work in relative isolation.

The influence may become apparent soon after the conclave starts. "One thing we know about groups is that they do tend to form status hierarchies very quickly," said Dr. Philip Tetlock, a professor at the Haas School of Business at the University of California, Berkeley. Dr. Moreland said the first ballot was important. "People will pay close attention," he said. "You might start to have coalitions in favor of certain candidates."

Coalition-forming will no doubt be spurred by the politicking that took place before the conclave. In interviews with the news media and in homilies during the days surrounding the pope's funeral, some cardinals tried to make a case, subtly, for one of their peers. Or for themselves.

But once the cardinals are inside, modern institutions like the media are forgotten. The college of cardinals has been charged with electing the pope for almost 1,000 years, and the first secluded conclave was held more than 700 years ago. The voting rules - the winner must receive a majority of two-thirds plus one - have existed with slight changes since 1179, although Pope John Paul II introduced a major change in 1996, requiring only a simple majority after a certain number of ballots.

The leaders who established the process seemed to know what they were doing. Indeed, a conclave might be close to the ideal group, said James Surowiecki, author of "The Wisdom of Crowds," about decision-making and group dynamics. "It's geographically and theologically diverse," he said. "And diversity is very important for groups to make smart decisions."

Dr. Moreland said the secrecy, which extends to the voting - cardinals are urged to disguise their handwriting when filling out ballots - may also help the process.

"You get much less conformity when people can respond anonymously," he said. "If nobody can tell you're defying the group, you have much less to fear."

Mr. Surowiecki said some members of the group may still "go along" with those of higher status, or those who are more talkative, or more confident. But higher status and verbosity do not necessarily correlate with greater intelligence or insight.

"The real paradox of group intelligence is that groups are smartest when everyone is acting as much like an individual as possible," Mr. Surowiecki said.

In the past, that has not always been possible. The conclave process was established in part to shelter against political or nationalist pressures, with limited success. Until the early 1900's, some Catholic nations had the right to veto a papal candidate.

Other pressures of a more physical nature have also been brought to bear. During a 13th-century conclave in Viterbo, Italy, one that might best be described as interminable (it lasted almost three years), the townspeople finally got fed up. They removed the palace roof to expose the cardinals to the elements, and sent in only bread and water. The deadlock quickly broke, and a layman was elected Pope Gregory X; he accomplished much in his five-year reign.

But there is no guarantee that the cardinals will make a good choice. Jerry B. Harvey, an emeritus professor of business at George Washington University, knows how a bad choice could happen. He has described what he calls the "Abilene paradox," when the pressure to conform based on fear makes people do things they don't want to do. (The name comes from a nightmarish car trip his family once took in Texas; when they got to Abilene, they realized that no one had wanted to go.) Dr. Harvey said he could imagine a situation in which the cardinals "would select somebody they'd all agree they didn't want."

It actually helps that the cardinals don't ordinarily spend a lot of time together. "If you know one another and don't want to rock the boat with each other," he said, "you end up going to Abilene."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top

Pier Paolo Cito/Associated Press

Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger asked God to give the church "a pastor according to his own heart, a pastor who guides us to knowledge in Christ, to his love and to true joy."

On the Sidelines, Catholic Liberals Still Seek a Ray of Hope

By IAN FISHER

ROME, April 16 - The idea was so preposterous that Sister Christine Schenk's first response was a long and resigned laugh. Would she and other liberal Catholics have any influence in the conclave that chooses a new pope?

"Oh, no, not at all," Sister Christine, director of FutureChurch, a coalition of progressive American Catholics, said in a telephone interview from Cleveland, where the group is based. "I think that is one of the difficulties with the conclave. Because you are a Catholic and because it doesn't happen very often, it feels like you are a team.

"But to think that there is any way to influence it is a complete fantasy." They may be idealists in general, but on this issue - the essential irrelevance of a liberal voice in this conclave - they are definite realists. Of the 115 cardinals taking part in the conclave, which begins on Monday, almost none of them have been outspoken on matters important to the liberal wing of the Catholic Church, like the ordination of women, more inclusion of laity in church business or easing bans on contraception.

Luigi De Paoli, one of the founders of We Are Church, the largest liberal church group in Europe, said his group had no cardinal inside the conclave representing its views. "We know some of them, and we think some of the most 'progressive' are in favor of our positions," he said. "But most of them are really conservative."

Still, liberals do not seem to despair (which is, anyway, a mortal sin for all stripes of Catholics). While questions like sexual morality do not appear to be on the table, that of collegiality - allowing bishops a greater say in adapting church doctrine locally - transcends the bounds of liberal and conservative. And many experts believe it will be one of the major issues discussed in the conclave, and could result in more local control, a change liberals would like.

Isaac Wüst, a liberal Catholic activist from the Netherlands, said that under Pope John Paul II, and especially in his later years, decisions came "from top to bottom, and no voices came from bottom to the top."

"Or at least no one was listening at the Vatican," he said. "That is what we want to change most of all," he added.

Like many matters facing the church, the liberal-conservative divide is not clear-cut: some liberals make the case that the conservative viewpoint dominating the Vatican and the College of Cardinals does not reflect ordinary Catholic life, and is one reason for declining church attendance in developed countries. But conservatives note that liberals do not represent all Catholics, particularly among the most devout.

Liberal groups themselves face contradictions. Although they say they represent Catholics around the world, their movements are based primarily in the United States and Europe, where church attendance is declining. In the third world, where the church is growing fastest, many Catholics remain deeply conservative, especially on sexual morality.

But even among the cardinals, easy definitions of liberal and conservative do not always fit. In the third world, many cardinals are conservative on sexual issues. In Latin America, many strongly oppose liberation theology, but are outspoken on poverty and social justice.

In Italy, one strong contender for the papacy, Dionigi Tettamanzi, the archbishop of Milan, is by most standards a conservative, especially on sexual morality, and is close to the conservative lay group Opus Dei. But he has sympathized with antiglobalists, and is outspoken on the need to find common ground with Muslims.

One progressive cardinal said the real divide in the College of Cardinals was simply between those who favored discussing delicate topics, like bioethics or sexual morality, and those who wanted them declared settled and off limits. Still, several activists said they believed that the reality of the church would force some changes.

Sister Christine noted that the dire shortage of priests and seminarians would have to be confronted. She said she hoped support would grow for the idea of married priests, and for allowing the ordination of women as deacons and someday priests.

"In the long term, our faith is with the Holy Spirit," said Linda Pieczynski, spokeswoman for Call to Action, based in Chicago, the largest Catholic reform group in the United States. "It's not with the individual men who govern the church."

"Jesus said the Spirit will always be with us," she added. "How else could the church have lasted for 2,000 years given the terrible leadership it has had at times?"

Daniel J. Wakin contributed reporting for this article.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top

Jake Price for The New York Times

A bishop, left, talked with a priest Friday night after attending a Mass in St. Peter's Basilica, three days before a conclave to elect the next pope begins.

April 16, 2005

Italians Feel They Need the Next Papacy for Themselves

By JASON HOROWITZ

VATICAN CITY, April 15 - For 455 years, the papacy passed uninterrupted from one Italian to another until the election of the Polish pope, John Paul II. Now, after 26 years, many Italians think it is time to get back in office - for fear that changes in the Roman Catholic Church may close the door on them for good.

As 115 cardinals from 52 countries prepare to enter a conclave on Monday to select the next pope, some Vatican historians believe that the election of another foreigner will conclude a historic shift of power away from Italy. According to this school of thought, the papacy needs to mirror Catholicism's growth in the Southern Hemisphere, where the ranks are increasing in Africa and Latin America while shrinking in Europe.

Few church experts think that another loss for the Italians will knock them out as papal contenders for good, but it seems sure once and for all to shatter the idea, reinforced by so many centuries of dominance, that Italians are preternaturally the best men for the job.

Some here think that would be a mistake.

"There is a vocation, an Italian charisma," said Vittorio Messori, an Italian writer who collaborated on John Paul's 1994 book "Crossing the Threshold of Hope." "The Italians have a tradition of centuries behind them, they know how to do the job of pope, it's in their DNA."

Well, until now, anyway. "Another non-Italian pope would confirm Italy's decline," said Giovanni Maria Vian, a Vatican scholar at La Sapienza University of Rome. "It would mean Italy has lost its central role in papal succession."

There are signs that Italy is resisting such a trend, seeking to reclaim its traditional hold and add to the 212 popes it has had in the church's history.

The 20 Italians who will enter next week's conclave still constitute the largest bloc of cardinals for any single nation, and a handful have emerged as frontrunners among those being considered for the papacy. In recent years, as the pope's health waned, a number of them maintained a high level of visibility and weighed in on major issues and challenges facing the church.

Cardinal Dionigi Tettamanzi, 71, the archbishop of Milan, released his major work on bio-ethics as an e-book. Cardinal Angelo Scola, 63, the archbishop of Venice, started a magazine last month promoting dialogue with Muslims, and Cardinal Camillo Ruini, 74, the vicar of Rome, published a book criticizing secularism.

There also seems to be a more subtle campaign, on the part of Italians as a whole, to recast John Paul as one of their own.

Cardinal Ruini presided over a memorial Mass for the pope last week, delivering an uncharacteristically charismatic performance in which he noted that John Paul had entered "so deeply into the hearts of Romans, but also Italians."

Italy's capital, too, has staked its claim, plastering the streets with posters announcing, "Rome mourns its pope." The College of Cardinals also decided that the pope's final resting place should be in St. Peter's crypt, instead of his native Poland.

Regardless of how much Rome may claim John Paul as its own, the fact remains that he was a pope with global appeal, and his enormous personality and long reign left an indelible stamp on the papacy.

"Wojtyla became the church himself, people identified him with it," said Pietro Scoppola, an Italian Vatican expert, using John Paul's name before he became pope. "An Italian could step back and let the church step forward."

Indeed, some Vatican analysts argue that a shift back to an Italian pope may be necessary to properly govern the Curia, or church government, because few have as intimate a knowledge of the inner workings of the Vatican bureaucracy, which manages the daily operations of the church and which John Paul largely ignored.

But an Italian cardinal, Fiorenzo Angelini, who is 88 and too old to vote in the conclave, seemed to disagree in an interview this week with Corriere della Sera of Milan.

"Our perception of the church has broadened, to the point of reaching really global dimensions," he said. "You can't reason any more with a national mentality, and not even a Continental one."

The largest growth of Roman Catholics in 2003, the last year Vatican statistics are available, was in Africa, followed by Asia and South America. Only in Europe did the number of Catholics fail to rise.

"The center of the church, from a sociological point of view, is not in Italy," said Giancarlo Zizola, author of "Conclave: History and Secrets," a study of how popes have been selected. "The world has changed, and it is normal that the church change too. There is good chance now of the first non-European pope in a very long time, and that would be significant."

Greek and Syrian popes reigned at the early stages of the nearly 2,000-year history of the church, and the French all but moved the Vatican to Avignon in the 1400's.

Since Adrian VI, a pope from Holland, died in 1523, the Italians have held a tight grip on papal power, through the rise and fall of the Papal States and two world wars. But in 1978, the year of John Paul's election, that all changed.

Wherever the pope is from, one thing is certain, and it is something that Pope John Paul instantly grasped during that first papal address from the balcony of St. Peter's so many years ago, when he spoke to the Roman crowd in what he called "our Italian language."

"Those who don't speak Italian are out," said Mr. Messori, the writer. "It's like wanting to be the secretary general of U.N. and not speaking English."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top

Pool photo by Bartlomiej Zborowski

In his homily, Cardinal Joseph Ratzinger -- a powerful Vatican official from Germany often mentioned as a leading candidate to become the next pope -- drew applause from fellow cardinals.

Venerable Papal Tradition: The Very Smoke-Filled Room

By Michael Farquhar

Washington Post Staff Writer

Sunday, April 17, 2005; Page D01

When the College of Cardinals assembles tomorrow to elect a new pope, many Catholics believe God's guiding hand will point them to the right man. Perhaps so. There certainly have been a number of inspired choices over the centuries. Yet in some of the most colorful elections of the past, the Holy Spirit seems to have taken a holiday.

This was particularly true during the Dark Ages, a low point in papal history, when worldly pontiffs ruled at the whim of powerful Roman aristocrats. Back then, before there was a College of Cardinals, family ties were a reliable way to secure the throne of St. Peter. (That is, for example, how John XI, reportedly the illegitimate son of Pope Sergius III and Marozia, a member of a powerful Roman family, became pope in 931.)

_____Electing a New Pope_____

? Election Process: Interactive graphic explains the process of electing a new pope and highlights possible successors.

? Profiles: Possible Successors

? Special Report: John Paul II

Holiness wasn't necessarily a prerequisite to becoming the Vicar of Christ in those days, nor was experience. Pope John XII was elected at the ripe age of 18, and proceeded to turn the Vatican into party central. The German emperor Otto I wrote the teenage pontiff with concern: "Everyone, clergy as well as laity, accuses you, Holiness, of homicide, perjury, sacrilege, incest with your relatives, including your sisters." Little wonder John was dubbed the "Christian Caligula."

Election to the papacy during this seemingly pagan era was no guarantee of job security. A third of the popes enthroned between 872 and 1012 died violently, some at the hands of their successors. Others were deposed for their wickedness and fled Rome in fear of their lives. These were dark ages indeed.

Stephen VII, elected during perhaps the darkest of those days, in 896, was quite possibly the craziest pope who ever ruled. Not long after his ascension, Stephen convened what has become known as "the Cadaver Synod." He ordered the corpse of his predecessor, Pope Formosus, dug out of its grave and dressed in full papal vestments. The late pope was then propped up for trial on a number of charges. After he was convicted, his body was tossed into the Tiber River. Stephen himself was deposed, imprisoned and strangled several months later.

Papal elections became a bit more exclusive in 1059, when the College of Cardinals was formed and given sole dominion over the process. Not much changed, however, since the group consisted mostly of the same lines of aristocrats who had been choosing popes for centuries.

The cardinals proved themselves spectacularly inefficient after the death of Clement IV in 1268, when they took nearly three years to elect his successor. As their deliberations dragged on, officials in Viterbo, Italy, locked them in the local palace, removed the roof to expose them to the elements, and threatened them with starvation if they didn't make a quick decision. Blessed Gregory X was eventually elected, and subsequently established many of the rules of conclave that are followed today.

During this period, the papacy was reaching the zenith of its power and glory. The pope, once merely the bishop of Rome, was now more of an emperor who claimed both spiritual and temporal dominion over all of Christendom.

"Who can doubt that the priests of Christ [popes] are to be considered the fathers and masters of kings and princes and all the faithful?" Saint Gregory VII declared late in the 11th century.

It was these imperial pretensions that made the papacy a much bigger prize. Accordingly, the succession became even more obstreperous as greedy cardinals grasped for it.

In 1294, Boniface VIII came to occupy the most powerful throne in the world and enjoy all the wealth that came with it, by reportedly whispering into his simple-minded predecessor's ear as he slept: "Celestine, Celestine, lay down your office. It is too much for you."

Boniface, the last of the mighty medieval popes, got his comeuppance when he was crushed by King Philip IV of France. The papacy was then moved from its ancient seat in Rome to the fortified city of Avignon, France. It would be nearly a century before Rome reclaimed the papacy. In 1378, the cardinals elected Pope Urban VI. He was not a good choice.

"I can do anything, absolutely anything I like," Urban proclaimed. This self-ordained license apparently included the torture and murder of six cardinals who dared to defy him.

Realizing they had a complete maniac on their hands, the remaining cardinals elected a new pope who promptly moved to France. Urban had no intention of budging from his throne in Rome, however. Instead, he appointed his own cardinals and ruled from there.

Now there were two duly elected popes and two colleges of cardinals -- one in France, one in Italy. It was a mess doomed to get even messier. Each side kept picking its own pope whenever a vacancy opened until finally the two conclaves of cardinals united and elected Alexander V in 1409. Only hitch was, neither of the old popes was willing to step down.

Now, with three popes on the job, something almost democratic happened. A council was formed, including both lower clergy and even laity, to sort through the various claims. The situation was ultimately resolved at the Council of Constance, where everyone was deposed in favor of Martin V in 1417 -- just in time for the coming Renaissance.

As the rest of the Western world harked back to ancient Greece in an explosion of art and literature, the papacy seemed to turn to the Dark Ages for inspiration. It was an era of some of the most unholy popes ever.

Competition among cardinals continued to be savage when a vacancy opened on the papal throne. Pope Pius II later recalled the intrigue surrounding the conclave that preceded his own election in 1458: "The richer and more powerful members begged, promised, threatened, and some, shamelessly casting aside all decency, pleaded their own cause and claimed the papacy as their right. Their rivalry was extraordinary, their energy unbounded. They took no rest by day or sleep by night."

Nevertheless, that conclave was positively decorous compared with the one several years later when Rodrigo Borgia nearly bankrupted himself to become Pope Alexander VI. Borgia bribed his fellow cardinals with bags of bullion, money he had earned selling pardons for all manner of crimes, and could barely contain his glee when he won.

"I am pope, I am pope," he exclaimed as he donned his sumptuous new vestments.

Saint Peter would have been so proud.