Saturday, June 04, 2005

California Coastal Commission

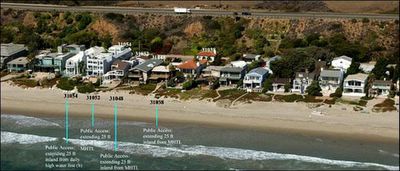

This land is my land: A state guide for sunbathers to Broad Beach in Malibu, showing how close the public can come to private property.

June 5, 2005

In Malibu, the Water's Fine (So Don't Come in!)

By MIREYA NAVARRO

MALIBU, Calif.

LAST Monday, two white wooden doors swung open for the first time onto Carbon Beach, courtesy of David Geffen, the DreamWorks co-founder, who owns a large shingled compound on the ocean and has the option of borrowing suntan lotion from billionaire neighbors like Eli Broad and Haim Saban. The mile-and-a-half-long beach, among the first glimpses of Malibu on the drive up from Los Angeles, is public by law, but to get to it, visitors must find a way to penetrate a wall of multimillion-dollar homes.

The famous Malibu coastline, the stuff of surfer lore and "Gidget" movies, is a battleground that heats up every summer. This year, the score is 1-0 in favor of the underdog: the beachgoer who appreciates exclusive comfort but can't afford it.

Mr. Geffen had agreed to allow a pathway to run alongside his property in 1983 in exchange for state permission to add a swimming pool and other expansions. But in 2002 he filed a lawsuit to fight the public's right to gain access to the beach at that spot. Earlier this year he relented.

Cameron Wellwood, 36, a guitar player in a band called the Harsh Carpets, was one of the first to pass through Mr. Geffen's gate.

"I can just come from across the street," said Mr. Wellwood, who lives on the oceanless side of the Pacific Coast Highway. "It just makes things so much more pleasant."

Before, to reach the waves just steps from his apartment, he had to walk two miles round trip to use another entry point.

He deemed the opening of the Geffen gate "monumental," which among Southern California beachgoers is no exaggeration. They contend with rules so confusing and restrictive that state officials and public interest groups have come up with maps to help people figure out where to walk or plop down their towels and umbrellas without disturbing homeowners.

The tension over space ricochets along Malibu's 27-mile coastline, where the homeowners include Steven Spielberg, Pierce Brosnan, Courteney Cox, Jeffrey Katzenberg and Richard J. Riordan, the former mayor of Los Angeles.

The homes are closed off on the street side, but the ocean side affords a democratic access that makes some of the famous dwellers nervous. The beach houses usually feature walls of windows facing the water, with open decks or expansive patios. Some owners, like Mr. Geffen, have their own guards and security cameras.

"One thing is not to want the public on the beach, but there's no excuse for not sharing the beach with your neighbors," Mr. Wellwood said as he took in the salty air.

"This is so typical of Malibu," he added.

The city, which joined Mr. Geffen in his lawsuit, is an epicenter for beach conflict, said officials with the California Coastal Commission, which regulates the use and development of the coast. The disputes here, however, tend to involve not drunken brawls and bad volleyball calls, but the tug between the public and the private interest.

Similar tensions are found in wealthy enclaves on both coasts, but in Malibu, which has 13,000 residents, they come with the complications of dense development, expensive real estate and a high celebrity quotient. Where else would you expect to stroll a few yards from Mel Gibson at a gathering with a group of nuns on a beachfront deck, or to bump into Mr. Spielberg walking along the water, as barefoot eyewitnesses claim to have done?

Some residents of Broad Beach, which is north of Carbon, up the Pacific Coast Highway, say they welcome visitors. But the homeowners' association puts up dozens of No Trespassing signs on the sand and hires patrols in all-terrain vehicles to keep people off private property in the summer.

"I'd be intimidated," said Lisa Haage, the chief of enforcement for the California Coastal Commission, which is negotiating a compromise with the homeowners' group. "When you go to the beach you want a happy day; you don't want armed conflict."

Made to feel as if they are crashing an A-list party, visitors to Broad Beach have been confined in the past to sitting in the narrow strips off two access ways, to play it safe. Yet many seek the hard-to-get-to beaches for the same reason some homeowners pay $5 million to $45 million for their properties: privacy.

Because it is often assumed that these beaches are off limits - and because of impediments like limited parking - crowds are often thin. There is none of the bustle of nearby Zuma Beach and other public beaches, which offer parking lots, food shacks and restrooms.

Dhana and Matthew Gilbert and their 14-month-old daughter, Riley, live in Pacific Palisades, a coastal community with its own beaches and celebs, including Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. But in the summer they drive 45 minutes up the Pacific Coast Highway for the quiet of Broad Beach, parking on the street near the access way.

"This feels like vacation," said Mrs. Gilbert, 37, a film production coordinator, who sat with her family under a blue umbrella last weekend near the sand dunes that shield some of the homes. "It's private. No music. It's cleaner."

But gazing out from his second-level terrace off the master bedroom, Marshall Grossman, an entertainment lawyer, was hardly as content as the Gilberts. He could see a woman and her dog crossing into his next-door neighbor's invisible property line.

"This woman here is clearly on private property," Mr. Grossman said. "If she were in Zuma Beach she'd be ticketed and her dog impounded."

Mr. Grossman, who is part of the 100-member homeowners' association and a former coastal commissioner, said the anxiety among neighbors is based on the behavior of a minority of troublemakers: strangers brazenly ensconced in lounge chairs and patio furniture belonging to homeowners; people who come with dogs or on horseback and fail to clean up after their animals; paparazzi who pretend to be surfers or dog walkers to sneak their shots; and fans looking for celebrities.

Some interlopers have even been caught taking showers, using the swimming pool or sleeping on a sofa in private homes, Mr. Grossman and other neighbors said.

"It's a little bit of a challenge," said Mark Attanasio, the owner of the Milwaukee Brewers, who ran into Mr. Grossman sometime later on the sand in front of Mr. Attanasio's 1940's Cape Cod-style cottage.

"If I went to their house and sat in their backyard, they wouldn't be pleased," Mr. Attanasio said. But Mr. Attanasio's backyard, so to speak, abuts the Pacific Ocean, an A-list attraction itself.

In general, visitors must stay within the mean high tide line. The rule of thumb is wherever the sand is wet, it is public. But the tide line that divides public from private moves every day.

To complicate matters further, some property owners, like Mr. Geffen, have allowed extra access beyond tide lines, from 25 feet to about 100 feet of dry sand in some cases, as part of agreements with state officials.

Some compromises meant to simplify the enforcement of the boundaries are in the works. In the meantime, at Carbon Beach, Access for All, the nonprofit group that waged battle with Mr. Geffen, is providing monitors and maps to explain the rules of the new access way to visitors.

"We're looking for a working relationship," said Steve Hoye, the director of the group. "If we have to be here with a tape measure, we'll have problems."

Andy Spahn, a spokesman for Mr. Geffen, said Mr. Geffen had no comment. But some of his neighbors said they had no problem with the idea of sharing the beach with more people.

"I do enjoy seeing people walking down the beach," said Dian Roberts, 78, who lives several doors from Mr. Geffen. What she did not appreciate, she said, was the portrayal of the Carbon Beach access conflict as a case of poor versus rich.

"I'm not rich," said Mrs. Roberts, who said she bought her land more than 50 years ago for less than $5,000, then spent an additional $20,000 building the house where she and her husband raised four children. "I just happen to have a house worth a pile."

Richard Terry, one among dozens of paparazzi who prowl the Malibu beaches looking for their next celebrity magazine shot, said star sightings were plentiful. He recently got an assignment to shoot a barbecue at Danny DeVito's house on Broad Beach and on his way there happened upon Dustin Hoffman riding a bicycle.

A few hours later, as if on cue, Amanda Carr, 18, a tourist from New Jersey, sauntered through the access way with a friend carrying multicolored beach towels. She said to Mr. Hoye, who stood at the entrance: "I want to see Britney Spears's house. Do you know where it is?"

Not on Carbon Beach, she was told.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Contact Us Back to Top

Harf Zimmerman

The Fast Lane: The Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren, for the driver who can't decide between a luxry sedan and a race car.

June 5, 2005

Speed Is of the Essence

By CHRISTOPHER S. STEWART

Ben Bradford is sitting behind the wheel of a half-million-dollar car on an old World War II airfield, about 40 miles outside of London. He smiles, but it's a sinister kind of smile. Bradford is a Mercedes service manager and an adrenaline junkie. The car is the Mercedes-Benz SLR McLaren. With its long, black surfboard hood, scissor doors and rear spoiler, the carbon-fiber supercoupe looks a lot like a stealth fighter and feels as fast.

''You ready?'' Bradford asks and slams the accelerator. Tires squeal. In 3.8 seconds, we pass 60 m.p.h. In 11 seconds, we're doing 120, all 617 horses of the handmade V-8 engine cranking. No whistling or shaking. But the ride is loud and raw. At 150, the engine is a primal roar and my back is pressed flat against the black leather seat. At 175, the peripheral world blurs, and my lungs are in my throat. ''Easy, isn't it?'' Bradford shouts, his hands loose on the steering wheel, as the needle hits 180.

The SLR started as a pipe dream, just a long-shot ''vision'' car at the 1998 Frankfurt auto show. But when people started talking, Mercedes and McLaren, the world-champion Formula 1 race shop, responded. It was an unusual alliance. Mercedes revels in large, luxury ?bersedans; McLaren is wedded to stripped-down speed. There were delays, disagreements and tension over how it would look and what would go inside. Ron Dennis, C.E.O. of McLaren, compares the competitive relationship to two men at the reins of a chariot. ''It's complicated,'' he said. ''There was always a rivalry on how we could do things better.''

When car fanatics talk about the SLR, which was finally introduced in August 2004, they talk about performance, elegance, function -- and price. In terms of speed, the car is in the same league as the Ferrari Enzo and the Porsche Carrera GT. With its 5.4-liter supercharged V-8, which sits midship, and a completely flat underbelly with scalloped diffusers at the back to reduce air resistance, enhance road traction and generate down force, the SLR tops out at around 207 m.p.h.

But unlike traditional steet-legal racers, the SLR is loaded with creature comforts: air-conditioning, ventilated seats, automatic transmission, Bose stereo system and enough trunk space for a set of golf clubs. It also has fiber-reinforced ceramic brakes, three sets of air bags, a rear wing that pops up when braking at speeds above 40 m.p.h. and a front-end crash structure made of carbon fiber, which is half the weight of steel and four times as strong. And early next year, custom colors will be available.

The McLaren Technology Center, which produces its Formula 1 line and the SLR, is in Woking, England. The building, a low-slung curve of steel and glass, was designed by Norman Foster at a reported cost of $300 million. Dennis calls it ''his advertising budget'' and describes the environment as Zenlike. Inside, the ceramic-tile floors gleam; the space is both dustless and odorless. More than 10,000 lights illuminate the mostly white space, which is large enough to accommodate nine 747's. Of the thousand workers, 100 are devoted to cleaning jobs like scrubbing floors and polishing glass, and nearly every one of them wears a black Hugo Boss uniform, described by Dennis as ''the doctor look.''

Like a Savile Row suit, the SLR is almost completely hand-crafted. Only 12 people are qualified to build the engine, which is shipped from Germany and personally signed by the engineer. ''We're talking about a very human process,'' Dennis said. Even at full capacity, when all 85 SLR ''doctors'' are working, you can practically hear a spark plug drop. On average, the car takes about 400 hours to build, with two polished SLR's leaving the factory daily. Compare that with Mercedes's total production: mostly machine-made vehicles churned out at a rate of 3,416 a day.

Still, even if you have $452,750 to burn, only 3,500 SLR's will be made, and the 500 to be built in 2005 have already been sold. Dealers are rumored to be holding some for ransom. On eBay, prices are hundreds of thousands of dollars above sticker. At a Christie's auction in New York, in December 2003, the first SLR sold to a Long Island woman for $2.1 million, the most ever paid for a new car. ''Once you get into this category, it's more than a waiting list,'' said Bernie Glaser, who heads passenger-car product management for Mercedes USA. ''It has a lot to do with whom the dealer wants to sell to.''

Back at the airfield, we're doing 183 m.p.h. I'm driving now. Bradford is laughing as we zigzag, the tires gripping fiercely. We cut a turn at 95. Just as it seems as if we're going to lose control and scream off into the grass, the tires grab the road.

Down the last straightaway, windows down, scenery rushing past, engine roaring and stereo blasting ''Pour Some Sugar on Me,'' Bradford yells, ''Stomp on it.'' I hit the brakes. The spoiler brake pops. There's hardly a skid. In seconds, we're at a dead stop. Bradford has driven the SLR dozens of times but still acts as if it's his first. ''Amazing,'' he says.

Christopher S. Stewart has written for Wired, GQ and The New York Times.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Contact Us Back to Top

A collision with the press.

How Do the Paparazzi Sell Their Pics?

An introduction to the celebrity photo game.

By Daniel Engber

Posted Friday, June 3, 2005, at 3:13 PM PT

A paparazzo photographer crashed a minivan into Lindsay Lohan's sports car on Tuesday; he now faces a possible charge of assault with a deadly weapon. The next day, Cameron Diaz filed suit against the National Enquirer for publishing a candid picture with the headline "Cameron Caught Cheating." How do the paparazzi sell their photos?

Most turn their snapshots over to a celebrity photo agency, which in turn sells them off to the highest bidder. (Some paparazzi do work independently or start their own agencies.) A typical deal gives 60 percent of the proceeds to the photographer and 40 percent to the middleman. If the photographer used information from the agency?such as, say, "Lindsay Lohan will be driving an SL65 coupe near the Beverly Center at rush hour"?the agency might take an additional 10 percent. That extra money often goes toward paying off inside sources such as bodyguards or personal assistants.

The word "paparazzi" comes from the celebrity shutterbug in Fellini's La Dolce Vita. Today, the term is often used to distinguish between reckless star-chasers and more conservative photographers who work official events and studio shoots. (These conservative types sometimes call their competitors the "stalkerazzi.") There are plenty of agencies that represent paparazzi?some of the best-known in Los Angeles are MB Pictures, Bauer-Griffin, X17, and Splash News.

Agencies try to sell pictures within 24 hours. The agency crops the images, adds captions, and wires them in digital form to publications around the world. (Sometimes these are sent in low resolution or with a watermark to discourage freeloaders.) Typically, a different deal gets cut for every country; the biggest players are the United States, the United Kingdom, Germany, and France. A publication will typically buy exclusive rights to print the photo for a few months.

Celebrity magazines and tabloids will also commission agencies to get certain pictures. If the editors at People wanted a shot of Denise Richards coming out of the hospital with a baby in her arms, they might offer photographers a few hundred dollars a day.

Publications often bid against each other for exclusive footage, and prices can get very high. Pictures of Brad Pitt and Angelina Jolie on the beach are said to have gone for $500,000 (though some paparazzi claim the actual figure was half that). The value of a photo depends on the story behind it: Shots of Denise Richards with her baby, for example, are worth more because of her separation from Charlie Sheen. Details are also important: An image of Denise smiling would be worth considerably more than a bland-faced equivalent.

With about 150 paparazzi in Los Angeles alone, it can be hard to find a photo that no one else has. If everyone gets the same red-carpet photo, it might only fetch a "space rate"?about $75 to $200, depending on the size of the published image. Exclusive shots net a great deal more, whether they're taken by the most aggressive paparazzi or a more austere agency like WireImage. An exclusive shot of a celebrity, taken by invitation in his or her home, can be worth tens of thousands of dollars.

Next question?

Explainer thanks Jay Williams of Shooting Star and Frank Griffin of Bauer-Griffin.

Daniel Engber is a writer in New York City and a featured member of www.cryingwhileeating.com.

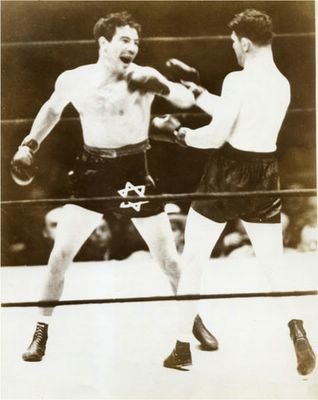

Max Baer (left) vs. James J. Braddock heavyweight championship fight, Long Island City, New York, June 13, 1935.

Fight Snub

How Cinderella Man sucker punches the Jewish boxer Max Baer.

By David Fellerath

Posted Thursday, June 2, 2005, at 12:51 PM PT

Attentive viewers of the climactic fight of Cinderella Man, Ron Howard's Depression-era crowd-pleaser, will notice a Star of David on the red trunks of Max Baer, the lethal opponent of Jim "Cinderella Man" Braddock. The star is significantly less prominent than the one that the real Baer wore in the 1935 fight. It's no surprise that Howard would obscure this detail, as it would complicate his film's Rocky-meets-Seabiscuit narrative. What's funny, and ironic, is that by downplaying Baer's Star of David, Howard may be making an accurate historical comment: Baer was the only self-proclaimed Jew to ever claim the heavyweight crown. But was he really even Jewish?

To be sure, Cinderella Man's fleeting portrait of Baer as a skirt-chasing playboy, notorious for clowning in the ring, is consistent with published accounts. Baer was also a ferocious hitter?a "larruping thumper," in the Times' gloriously redundant formulation. In his early career, he secured a fearsome reputation on the West Coast, killing a boxer named Frankie Campbell during a 1930 bout. The tragedy so rattled Baer that he lost four of his next six fights. In the film, the death of Campbell is used to build up Baer as a remorseless killer. One movie's terrifying thug, however, is another man's father. "It was after he killed Campbell that he started clowning," Maxie Baer Jr. said in a recent telephone conversation from Las Vegas. "He started smoking cigarettes and he had nightmares for years."

After Campbell's death, Baer decided to move east and train under the tutelage of Jack Dempsey. It was in 1933, when Baer was 24, that he came out as a Jew and wore the Star of David on his trunks for the first time. His opponent was Max Schmeling, the "Black Uhlan of the Rhine" and a reluctant standard-bearer for Hitler's Third Reich. "That one's for Hitler," Baer snarled between blows to the stumbling Schmeling. He knocked him out in the 10th round. It was his finest hour in the ring.

In the post-fight coverage, however, Baer's new "racial" identity raised eyebrows. As reported in the New York Times:

[Baer] explained yesterday, however, that he wore this insignia for the first time, because he is partly Jewish. "My father is Jewish and my mother is Scotch-Irish," said Baer. "I wore the insignia because I thought I should, and I intend to wear it in every bout hereafter."

Over the years, the significance of Baer's gesture has been dismissed as a publicity stunt in a sport that thrives on racial and ethnic conflict. Jeremy Schaap, the author of Cinderella Man: James J. Braddock, Max Baer, and the Greatest Upset in Boxing History, takes a more nuanced view. Schaap establishes that Baer's father was at least half-Jewish before arguing that Baer's manager, Ancil Hoffman, stoked his boxer's ethnic consciousness as a motivating tool. Baer Jr. confirms this view. "My dad didn't know who Hitler was. He only read the sports pages, but Hoffman kept drilling it into his head, 'You're fighting for the Jews.' "

Baer's prominent display of the Star of David came at a time of continuous bad tidings from Germany. Anti-Jewish boycotts were under way, Jews were being expelled from official positions, and Dachau had opened for the internment of communists. A day after the Schmeling fight, a Times dispatch from Berlin reported that the German papers were reticent about their countryman's defeat. "All papers ignore the fact that Schmeling was beaten by a man who in Germany would be classified as a Jew," the unnamed Times correspondent wrote. One can only imagine the propaganda uses Joseph Goebbels would have found had Schmeling defeated Baer.

By disposing of Schmeling, Baer earned his title shot against another unfortunate show horse for European political fashion, Primo "the Ambling Alp" Carnera, a 6-foot-6-inch, 263-pound former circus strongman and a mobbed-up mascot for Benito Mussolini. This 1934 fight?briefly but vividly re-enacted in Cinderella Man?was a frightful affair in which Baer knocked down the clumsy giant 11 (or 12) times, despite being outweighed by 53 pounds.

The heavyweight title now belonged to Baer, who would hold it for 364 days of nightclub carousing and adoring magazine articles. In a 1934 Vanity Fair profile, Baer is described by a bemused Westbrook Pegler in strikingly Gatsby-like terms, a striver taking "dago-singing" lessons and "long-wording people into a daze" from a pocket dictionary. More presciently, Pegler also wrote, "Baer is a fast swinger and he probably will keep the title until frivolity, late hours and cigars abate his speed by the fraction of an instant. Then, presumably, a scientific boxer will beat him. ?"

That studiously determined upstart turned out to be gritty Jimmy Braddock from the Jersey docks, known by the more fitting "Plain Jim" before Damon Runyon tagged him "Cinderella Man." Braddock's tale is indeed inspiring: He had a family to feed while Baer's expenses ran mostly to his wardrobe and his mistresses. Baer Jr. cheerfully admits that his father was woefully unprepared. "He didn't take Braddock seriously, he didn't train, and he got a b.j. before the fight," he says, apparently listing the offenses in ascending order of gravity.

Despite the star on his trunks that night, Baer was never a practicing Jew. His tenuous claim, however, seems to have been good enough for Jewish fight fans. Schaap writes that, on the night of the Braddock fight, "Of the 30,000 people in the Bowl, virtually everyone except the Jews was cheering for Braddock."

Stepping back, Baer's "Jewishness" was only one aspect of his elaborate self-invention. In 1933 he starred with Myrna Loy and his upcoming opponent Primo Carnera in The Prizefighter and the Lady, in which he played an all-American underdog who challenges Carnera for the championship. The film was a success and Baer received good reviews for a role that included singing and dancing. It played for a while in Germany, until Goebbels banned the film because Baer was in the cast. But his most enduring film is the 1956 anti-boxing expos? The Harder They Fall, adapted from a Budd Schulberg novel. The film is a virtually undisguised scandal-mongering account of events leading up to the Baer-Carnera fight of 1934. While the justifiably aggrieved Carnera sued Columbia Pictures and Schulberg, Baer gamely played a vicious caricature of himself, a portrait not unlike the Baer we see in Cinderella Man. Schulberg slammed The Harder They Fall as naively sensationalistic, singling out the film's use of Baer: "Maxie Baer, who queens through this incredible part, may have been a tamed tiger but he wasn't a monster."

Even though Baer underachieved as a boxing talent, he still has the distinction of being a feared fighter who wore a conspicuous Star of David on his trunks in the dangerous years of the 1930s. He died of a massive heart attack at the age of 50 in 1959. (Among other things, he didn't live to see his son achieve television celebrity as Jethro Bodine on The Beverly Hillbillies.) Cinderella Man may reduce Baer to a crude and simplistic villain, but Baer probably would have enjoyed the movie anyway?he despised boxing. "He thought it was horseshit," says his son. "He really wanted to be an actor."

David Fellerath writes about movies for the Independent Weekly of Durham, N.C

Oliver Meckes/Nicole Ottawa/ Photo Researchers, Inc.

One gene, apparently by itself, creates patterns of sexual behavior in fruit flies.

June 3, 2005

For Fruit Flies, Gene Shift Tilts Sex Orientation

By ELISABETH ROSENTHAL,

International Herald Tribune

When the genetically altered fruit fly was released into the observation chamber, it did what these breeders par excellence tend to do. It pursued a waiting virgin female. It gently tapped the girl with its leg, played her a song (using wings as instruments) and, only then, dared to lick her - all part of standard fruit fly seduction.

The observing scientist looked with disbelief at the show, for the suitor in this case was not a male, but a female that researchers had artificially endowed with a single male-type gene.

That one gene, the researchers are announcing today in the journal Cell, is apparently by itself enough to create patterns of sexual behavior - a kind of master sexual gene that normally exists in two distinct male and female variants.

In a series of experiments, the researchers found that females given the male variant of the gene acted exactly like males in courtship, madly pursuing other females. Males that were artificially given the female version of the gene became more passive and turned their sexual attention to other males.

"We have shown that a single gene in the fruit fly is sufficient to determine all aspects of the flies' sexual orientation and behavior," said the paper's lead author, Dr. Barry Dickson, senior scientist at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology at the Austrian Academy of Sciences in Vienna. "It's very surprising.

"What it tells us is that instinctive behaviors can be specified by genetic programs, just like the morphologic development of an organ or a nose."

The results are certain to prove influential in debates about whether genes or environment determine who we are, how we act and, especially, our sexual orientation, although it is not clear now if there is a similar master sexual gene for humans.

Still, experts said they were both awed and shocked by the findings. "The results are so clean and compelling, the whole field of the genetic roots of behavior is moved forward tremendously by this work," said Dr. Michael Weiss, chairman of the department of biochemistry at Case Western Reserve University. "Hopefully this will take the discussion about sexual preferences out of the realm of morality and put it in the realm of science."

He added: "I never chose to be heterosexual; it just happened. But humans are complicated. With the flies we can see in a simple and elegant way how a gene can influence and determine behavior."

The finding supports scientific evidence accumulating over the past decade that sexual orientation may be innately programmed into the brains of men and women. Equally intriguing, the researchers say, is the possibility that a number of behaviors - hitting back when feeling threatened, fleeing when scared or laughing when amused - may also be programmed into human brains, a product of genetic heritage.

"This is a first - a superb demonstration that a single gene can serve as a switch for complex behaviors," said Dr. Gero Miesenboeck, a professor of cell biology at Yale.

Dr. Dickson, the lead author, said he ran into the laboratory when an assistant called him on a Sunday night with the results. "This really makes you think about how much of our behavior, perhaps especially sexual behaviors, has a strong genetic component," he said.

All the researchers cautioned that any of these wired behaviors set by master genes will probably be modified by experience. Though male fruit flies are programmed to pursue females, Dr. Dickson said, those that are frequently rejected over time become less aggressive in their mating behavior.

When a normal male fruit fly is introduced to a virgin female, they almost immediately begin foreplay and then copulate for 20 minutes. In fact, Dr. Dickson and his co-author, Dr. Ebru Demir of the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology, specifically chose to look for the genetic basis of fly sexual behavior precisely because it seemed so strong and instinctive and, therefore, predictable.

Scientists have known for several years that the master sexual gene, known as fru, was central to mating, coordinating a network of neurons that were involved in the male fly's courtship ritual. Last year, Dr. Bruce Baker of Stanford University discovered that the mating circuit controlled by the gene involved 60 nerve cells and that if any of these were damaged or destroyed by the scientists, the animal could not mate properly. Both male and female flies have the same genetic material as well as the neural circuitry required for the mating ritual, but different parts of the genes are turned on in the two sexes. But no one dreamed that simply activating the normally dormant male portion of the gene in a female fly could cause a genetic female to display the whole elaborate panoply of male fruit fly foreplay.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Contact Us Back to Top

Pool photo by Joshua Gates WeisbergMichael Jackson arrived at court Thursday in Santa Maria, Calif., for the first day of closing arguments in his child-molesting trial.

June 3, 2005

Final Arguments in Jackson Trial Paint 2 Portraits

By JOHN M. BRODER

SANTA MARIA, Calif., June 2 - As they did through three months of sometimes bizarre testimony, lawyers for both sides in the child-molesting trial of Michael Jackson painted widely divergent portraits in their final arguments on Thursday of a singer whose fame once rivaled that of Elvis and the Beatles but who has in recent years retreated into a strange and private world.

Soon a jury of eight women and four men will be asked to cast a verdict on the man and his world, with incalculable consequences for his career, his fortune, his reputation, even his health. But whatever the jury finds, Mr. Jackson has been indelibly damaged by his tribulation in a central California courtroom, his secrets laid bare and his psyche picked apart as if by carrion birds.

The trial here is only the latest in a decade of reversals for Mr. Jackson, whose music career is stalled and whose debts are piling up at a dizzying pace. Even if he is acquitted, many people will continue to believe that he harbors an unhealthy fondness for young boys, whom he openly admits inviting into his bed. He insulates himself from reality at his 2,700-acre Neverland Valley Ranch, surrounded by zoo animals and well-paid loyalists who do not question his odd behavior.

Ronald J. Zonen, a senior deputy district attorney, called Mr. Jackson a "predator" who feasted upon weak boys from fatherless homes, luring them into his bedroom with long conversations and lavish gifts, then softening them up for sexual molesting with alcohol and pornography. The accuser in this case, a 15-year-old recovering cancer patient, is but the latest in a line of victims that goes back more than a decade, the prosecutor said.

By day, Mr. Zonen said, the boys played at Neverland, driving customized go-karts, playing the latest video games, enjoying carnival rides and gorging themselves on candy and ice cream.

"At night," Mr. Zonen said, "they entered into the world of the forbidden in Mr. Jackson's bedroom. Mr. Jackson's room was a veritable fortress, with locks and codes which the boys were given. And they learned about human sexuality from someone who was only too willing to be their teacher."

Mr. Jackson's lead lawyer, Thomas A. Mesereau Jr., dismissed the prosecution's account as a lurid fantasy woven by enemies of Mr. Jackson and a family seeking to exploit his fame and riches to become wealthy itself.

Mr. Mesereau described the accuser and his family as "con artists, actors and liars" who had insinuated themselves into Mr. Jackson's life and the lives of many other celebrities as part of a pattern of fraud and deceit. He said Mr. Jackson, whom he described as "childlike and different and offbeat and na?ve," had been the victim of such hustlers repeatedly in his life. That is why he is in constant financial trouble and frequently the target of schemers, Mr. Mesereau said.

The jury listened raptly to the two lawyers' arguments, which took all day on Thursday and are expected to be completed by midday Friday. A few of the 12 jurors and 8 alternates took notes. Mr. Jackson, clad in a dark suit and plaid vest, appeared to be paying attention, but his facial expression rarely changed.

Mr. Zonen flashed pictures of Mr. Jackson and a succession of young boys he had befriended, and, Mr. Zonen suggested, sexually abused. He also showed covers of pornographic magazines featuring young female models and pictures of nude adolescent boys from books found in Mr. Jackson's home.

Mr. Mesereau's visual aids consisted chiefly of slides reminding jurors of inconsistent testimony and a timeline of the alleged molesting that he said was utterly incredible.

In the seats directly behind the defense table sat the defendant's brothers Tito and Randy, members of the original Jackson Five, accompanied during the afternoon by Dick Gregory, the comedian and social activist.

Mr. Jackson's parents, Katherine and Joe, sat in the second row, as they have most days during the 65 days of at times excruciating testimony about their son's taste in pornography, the figurines of nude women in bondage outfits found in his bedroom, his alleged heavy drinking and his supposed practice of licking the heads of young boys - all of which Mr. Zonen reminded jurors of on Thursday.

The Santa Barbara County district attorney, Thomas W. Sneddon Jr., who has sought to put Mr. Jackson behind bars for more than a decade, chose to allow his deputy to deliver the closing argument. Mr. Zonen proved during trial to be a more effective questioner than his boss and appeared to have better rapport with the jury.

He delivered his argument in rapid-fire style with a tone of barely suppressed outrage at Mr. Jackson's behavior.

"This case is about the exploitation and sexual abuse of a 13-year-old cancer survivor by an international celebrity," he said at the beginning of his statement. He then tried to defend the boy's mother, whom the defense has portrayed as a grifter, as an abused spouse struggling to raise three teenagers and who never asked anyone for money.

Mr. Zonen acknowledged that she had committed welfare fraud by claiming benefits within days of receiving $32,000 in a civil settlement in a case she filed against J. C. Penney. "That was a bad mistake on her part, and she may yet have to suffer the consequences before this is all over with," he said.

Later, he described what he called Mr. Jackson's "grooming" of boys for sexual molesting. It begins with the selection of a vulnerable child, Mr. Zonen said.

"The lion on the Serengeti doesn't go after the strongest antelope," he said. "The predator goes after the weakest."

He said the accuser's testimony was credible and consistent and sufficient grounds to convict Mr. Jackson. "The suggestion that all this was planned and plotted and was part of a shakedown is nonsense," he said. "It's unmitigated rubbish."

Mr. Mesereau, whose tone ranged from angry to sarcastic to scornful, noted that Mr. Zonen had spent a sizable chunk of his time for closing arguments in an attack on Mr. Mesereau and what Mr. Zonen called Mr. Mesereau's broken promises to the jury in his opening statement.

"When a prosecutor does that, you know he's in trouble," Mr. Mesereau said, looking straight at the jury. "This is not a popularity contest between lawyers. This is about the life, the future, the freedom and the reputation of Michael Jackson. That's what is about to be placed in your hands."

He said the prosecution's case rose or fell on the credibility of the accuser, his brother and his mother. "You've got to believe them beyond a reasonable doubt," he said. "You've got to believe them all the way. And it's impossible."

Mr. Mesereau said the prosecution had introduced the pornography found at Neverland into the trial without any direct evidence that the singer had shown any of it to the accuser. He said it was part of a "mean-spirited, nasty, barbaric attempt to demonize Mr. Jackson."

He added: "They have dirtied him up because he's human. But they haven't proven their case. They can't."

He said the accuser and his brother were cunning and street-smart youths from the east side of Los Angeles who had been coached by their parents to ingratiate themselves with celebrities and then wheedle money out of them. They raided the liquor cabinets at Neverland and brought their own "girlie" magazines, Mr. Mesereau said.

According to the prosecution, he said, "it was all Michael Jackson taking these innocent little lambs and corrupting their minds, and it's baloney."

Mr. Mesereau said that this case had turned Mr. Jackson's life "topsy-turvy," and had left him lonely and unable to trust anyone around him. "But he's not a criminal," Mr. Mesereau said.

As he was leaving the courtroom at the end of a draining day, Mr. Jackson was asked how he felt. He tented his fingers before him and whispered, "I'm O.K."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Contact Us Back to Top

Nicole Bengiveno/The New York Times

Godiva sells chocolate at 2,500 outlets, including its store on Madison Avenue in Manhattan. But its expensive "G" line, at $100 a pound, is available only in holiday seasons and at selected stores.

May 29, 2005

When the Joneses Wear Jeans

By JENNIFER STEINHAUER

BEACHWOOD, Ohio - It was 4:30 p.m., sweet hour of opportunity at the Beachwood Place Mall.

Shoppers were drifting into stores in the rush before dinner, and the sales help, as if on cue, began a retail ritual: trying to tell the buyers from the lookers, the platinum-card holders from those who could barely pay their monthly minimum balance.

It is not always easy. Ellyn Lebby, a sales clerk at Saks Fifth Avenue, said she had a customer who regularly bought $3,000 suits but "who looks like he should be standing outside shaking a cup."

At Oh How Cute, a children's boutique, the owner, Kira Alexander, checks out shoppers' fingernails. A good manicure usually signals money. "But then again," Ms. Alexander conceded, "I don't have nice nails and I can buy whatever I want."

Down the mall at the Godiva chocolate store, Mark Fiorilli, the manager, does not even bother trying to figure out who has money. Over the course of a few hours, his shoppers included a young woman with a giant diamond ring and a former airplane parts inspector living off her disability checks.

"You can't make assumptions," Mr. Fiorilli said.

Social class, once so easily assessed by the car in the driveway or the purse on the arm, has become harder to see in the things Americans buy. Rising incomes, flattening prices and easily available credit have given so many Americans access to such a wide array of high-end goods that traditional markers of status have lost much of their meaning.

A family squarely in the middle class may own a flat-screen television, drive a BMW and indulge a taste for expensive chocolate.

A wealthy family may only further blur the picture by shopping for wine at Costco and bath towels at Target, which for years has stocked its shelves with high-quality goods.

Everyone, meanwhile, appears to be blending into a classless crowd, shedding the showiest kinds of high-status clothes in favor of a jeans-and-sweatsuit informality. When Vice President Dick Cheney, a wealthy man in his own right, attended a January ceremony in Poland to commemorate the liberation of Nazi death camps, he wore a parka.

But status symbols have not disappeared. As luxury has gone down-market, the marketplace has simply gone one better, rolling out ever-pricier goods and pitching them to the ever-loftier rich. This is an America of $130,000 Hummers and $12,000 mother-baby diamond tennis bracelet sets, of $600 jeans, $800 haircuts and slick new magazines advertising $400 bottles of wine.

Then there are the new badges of high-end consumption that may be less readily conspicuous but no less potent. Increasingly, the nation's richest are spending their money on personal services or exclusive experiences and isolating themselves from the masses in ways that go beyond building gated walls.

These Americans employ about 9,000 personal chefs, up from about 400 just 10 years ago, according to the American Personal Chef Association. They are taking ever more exotic vacations, often in private planes. They visit plastic surgeons and dermatologists for costly and frequent cosmetic procedures. And they are sending their children to $400-an-hour math tutors, summer camps at French chateaus and crash courses on managing money.

"Whether or not someone has a flat-screen TV is going to tell you less than if you look at the services they use, where they live and the control they have over other people's labor, those who are serving them," said Dalton Conley, an author and a sociologist at New York University.

Goods and services have always been means to measure social station. Thorstein Veblen, the political economist who coined the phrase "conspicuous consumption" at the beginning of the last century, observed that it was the wealthy "leisure class," in its "manner of life and its standards of worth," that set the bar for everyone else.

"The observance of these standards," Veblen wrote, "in some degree of approximation, becomes incumbent upon all classes lower in the scale."

So it is today. In a recent poll by The New York Times, fully 81 percent of Americans said they had felt social pressure to buy high-priced goods.

But what Veblen could not have foreseen is where some of that pressure is coming from, says Juliet B. Schor, a professor of sociology at Boston College who has written widely on consumer culture. While the rich may have always set the standards, Professor Schor said, the actual social competition used to be played out largely at the neighborhood level, among people in roughly the same class.

In the last 30 years or so, however, she said, as people have become increasingly isolated from their neighbors, a barrage of magazines and television shows celebrating the toys and totems of the rich has fostered a whole new level of desire across class groups. A "horizontal desire," coveting a neighbor's goods, has been replaced by a "vertical desire," coveting the goods of the rich and the powerful seen on television, Professor Schor said.

"The old system was keeping up with the Joneses," she said. "The new system is keeping up with the Gateses."

Of course only other billionaires actually can. Most Americans are staring across a widening income gap between them and the very rich, making such vertical desire all the more unrealistic. "There is a bigger gap between the average person and what they are aspiring to," Professor Schor said.

But others who study consumer behavior say that the wanting and getting of material goods is not just a competitive exercise. In this view, Americans care less about emulating the top tier than about simply having a fair share of the bounty and a chance to carve out a place for themselves in society.

"People like having stuff, and stuff is good for people," said Thomas O'Guinn, a professor of advertising at the University of Illinois who has written textbooks on marketing and consumption. "One thing modernity brought with it was all kinds of identities, the ability for people to choose who you want to be, how you want to decorate yourself, what kind of lifestyle you want. And what you consume cannot be separated from that."

Falling Prices, Rising Debt

Throughout the mall in this upscale suburb of Cleveland, high-priced merchandise was moving: $80 cotton rompers at Oh How Cute, $40 scented candles at Bigelow Pharmacy. And everywhere, it seemed, was the sound of cellphones, one ringing out with a salsa tune, another with bars from Brahms.

Few consumer items better illustrate the democratization of luxury than the cellphone, once immortalized as the ultimate toy of exclusivity by Michael Douglas as he tromped around the 1987 movie "Wall Street" screaming into one roughly the size of a throw pillow.

Now, about one of every two Americans uses a cellphone; last year, there were 176 million subscribers, almost eight times the number a decade ago, according to the market research firm IDC. The number has soared because prices have correspondingly plummeted, to about an eighth of what they were 10 years ago.

The pattern is a familiar one in consumer electronics. What begins as a high-end product - a laptop computer, a DVD player - gradually goes mass market as prices fall and production rises, largely because of the cheap labor costs in developing countries that are making more and more of the goods.

That sort of "global sourcing" has had a similar impact across the American marketplace. The prices of clothing, for example, have barely risen in the last decade, while department store prices in general fell 10 percent from 1994 to 2004, the federal government says.

Even where luxury-good prices have remained forbiddingly high, some manufacturers have come up with strategies to cast more widely for customers, looking to middle-class consumers, whose incomes have generally risen in recent years; the median family income in the United States grew 17.6 percent from 1983 to 2003, when adjusted for inflation.

One way makers of luxury cars have tapped into this market is by introducing cheaper versions of their cars, trying to lure younger, less-affluent buyers in the hope that they may upgrade to more prestigious models as their incomes grow.

Mercedes-Benz, BMW and Audi already offer cars costing about $30,000 and now plan to introduce models that will sell for about $25,000. Entry-level luxury cars are the fastest growing segment of that industry.

"The big new trend that is coming to the U.S. is 'subluxury' cars," said David Thomas, editor of Autoblog, an online automotive guide. "The real push now is to go a step lower, but the car makers won't say 'lower.' "

The luxury car industry is just one that has made its products more accessible to the middle class. The cruise industry, once associated with the upper crust, is another.

"The cruise business has totally evolved," said Oivind Mathisen, editor of the newsletter Cruise Industry News, "and become a business that caters to moderate incomes." The luxury end makes up only 10 percent of the cruise line market now, Mr. Mathisen said.

Yet today's cruise ships continue to trade on the vestiges of their upper-class mystique, even while offering new amenities like on-board ice skating and wall-climbing. Though dinner with the captain may be a thing of the past, the ships still pamper guests with spas, boutiques and sophisticated restaurants.

All that can be had for an average of $1,500 a week per person, a price that has gone almost unchanged in 15 years, Mr. Mathisen said. The industry has kept prices down in part by buying bigger ships, the better to accommodate a broader clientele.

But affordable prices are only one reason the marketplace has blurred. Americans have loaded up on expensive toys largely by borrowing and charging. They now owe about $750 billion in revolving debt, according to the Federal Reserve, a six-fold increase from two decades ago.

That huge jump can be traced in part to the credit industry's explosive growth. Over the last 20 years, the industry became increasingly lenient about whom it was willing to extend credit to, more sophisticated about assessing credit risks and increasingly generous in how much it would let people borrow, as long as those customers were willing to pay high fees and risk living in debt.

As a result, to take one example, millions of Americans who could not have dreamed of buying their own homes two decades ago are now doing so in record numbers because of a sharp drop in mortgage interest rates, a surge in the number of mortgages granted and the creation of the sub-prime lending industry, which gives low-income people access to credit at high cost.

"Creditors love the term the 'democratization of credit,' " said Travis B. Plunkett, the legislative director of the Consumer Federation of America, a consumer lobbying group. "Over all, it has certainly had a positive effect. Many families that never had access to credit now do. The problem is that a flood of credit is now available to many financially vulnerable families and extended in a reckless and aggressive manner in many cases without thought to implications. The creditors say it has driven the economy forward and helped many families improve their financial lives, but they omit talking about the other half of the equation."

The Marketers' Response

Marketers have had to adjust their strategies in this fluid world of consumerism. Where once they pitched advertisements primarily to a core group of customers - men earning $35,000 to $50,000 a year, say - now they are increasingly fine-tuning their efforts, trying to identify potential customers by interests and tastes as well as by income level.

"The market dynamics have changed," said Idris Mootee, a marketing expert based in Boston. "It used to be clearly defined by how much you can afford. Before, if you belonged to a certain group, you shopped at Wal-Mart and bought the cheapest coffee and bought the cheapest sneakers. Now, people may buy the cheapest brand of consumer goods but still want Starbucks coffee and an iPod."

Merchandisers, for example, might look at two golfers, one lower middle class, the other wealthy, and know that they read the same golf magazine, see the same advertisements and possibly buy the same quality driver. The difference is that one will be splurging and then play on a public course while the other will not blink at the price and tee off at a private country club.

Similarly, a middle-income office manager may save her money to buy a single luxury item, like a Chanel jacket, the same one worn by a wealthy homemaker who has a dozen others like it in her $2.5 million house.

Marketers also know that today's shoppers have unpredictable priorities. Robert Gross, who was wandering the Beachwood mall with his son David, said he couldn't live without his annual cruise. Mr. Gross, 65, also prizes his two diamond pinkie rings, his racks of cashmere sweaters and his Mercedes CLK 430. "My license plate reads BENZ4BOB," he said. "Does that tell you what kind of person I am?"

But a taste for luxury goods did not stop Mr. Gross, an accountant, from scoffing as David paid $30 for a box of Godiva chocolates for his wife. The elder Mr. Gross had been to a local chocolate maker. "I went to Malley's," he said, "and bought my chocolate half price."

Yet virtually no company that has built a reputation as a purveyor of luxury goods will want to lose its foothold in that territory, even as it lowers prices on some items and sells them to a wider audience. If one high-end product has slipped into the mass market, then a new one will have to take its place at the top.

Until the early 1990's, Godiva sold only in Neiman Marcus and a few other upscale stores. Today it is one of those companies whose customers drift in from all points along the economic spectrum. Its candy can now be found in 2,500 outlets, including Hallmark card stores and middle-market department stores like Dillard's.

"People want to participate in our brand because we are an affordable luxury," said Gene Dunkin, president of Godiva North America, a unit of the Campbell Soup Company. "For under $1 to $350, with an incredible luxury package, we give the perception of a very expensive product."

But the company is also trying simultaneously to hold on to the true luxury market, which has increasingly been seduced away by small, expensive artisan chocolate makers, many from Europe, that are opening around the country. Two years ago, Godiva introduced its most expensive line ever, "G," handmade chocolates selling for $100 a pound. Today it is available only in holiday seasons and only at selected stores.

The New Status Symbols

While the rest of the United States may appear to be catching up with the Joneses, the richest Joneses have already moved on.

Some have slipped out of sight, buying bigger and more lavish homes in neighborhoods increasingly insulated from the rest of Americans. But the true measure of upper class today is in the personal services indulged in.

Professor Conley, the New York University sociologist, refers to these less tangible badges of status as "positional goods." Consider a couple who hire a baby sitter to pick up their children from school while they both work, he said. Their status would generally be lower than the couple who could pick up their children themselves, because the second couple would have enough earning power to allow one parent to stay at home while the other worked.

But the second couple would actually occupy the second rung in this after-school hierarchy. "In the highest group of all is the parent who has a nanny along," Professor Conley said.

Status among people in the top tier, he said, "is the time spent being waited on, being taken care of in nail salons, and how many people who work for them." From 1997 to 2002, revenues from hair, nail and skin care services jumped by 42 percent nationwide, Census Bureau data shows. Revenues from what the bureau described as "other personal services" increased 74 percent.

Indeed, in some cases, services and experiences have replaced objects as the true symbols of high status. "Anyone can buy a one-off expensive car," said Paul Nunes, who with Brian Johnson wrote "Mass Affluence," a book on marketing strategies. "But it is lifestyle that people are competing on more now. It is which sports camps do your kids go to and how often, which vacations do you take, even how often do you do things like go work for Habitat for Humanity, which is a charitable expense people can compete with."

In the country's largest cities, otherwise prosaic services have been transformed into status symbols simply because of the price tag. In New York last year, one salon introduced an $800 haircut, and a Japanese restaurant, Masa, opened with a $350 prix fixe dinner (excluding tax, tips and beverages). The experience is not just about a good meal, or even an exquisite one; it is about a transformative encounter in a Zen-like setting with a chef who decides what will be eaten and at what pace. And it is finally about exclusivity: there are only 26 seats. Today, one of the most sought-after status symbols in New York is a Masa reservation.

And that is how the marketplace works, Professor Conley says. For every object of desire, another will soon come along to trump it, fueling aspirations even more.

"Class now is really like three-card monte," he said. "The moment the lower-status aspirant thinks he has located the nut under the shell, it has actually shifted, and he is too late. "

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Contact Us Back to Top

All classed up and nowhere to go

The New York Times goes slumming: How the paper?s allegiance to the ruling elite distorts its look at class in America

BY CHRIS LEHMANN

CLASS REALLY DOES MATTER: by reducing 'class' to behavior and culture, the Grey Lady ignored cold economic truths and looked down her nose at how the other half -- and growing -- lives.

AT FIRST GLANCE, "Class Matters" ? the New York Times? epic inquiry into the widening economic divisions of the new millennium ? appears to be what its editors solemnly claim: a well-intentioned effort to reckon with a serious social condition, one that notoriously eludes clear understanding in America, so long hymned as the planet?s pre-eminent land of opportunity. Alas, however, the New York Times is in no position to deliver. In contrast to, say, the paper?s conscientious reporting on the ?60s-era civil-rights movement in the South, its foray into class consciousness suffers from a fatal flaw. Social class is at the core of the Times? institutional identity, which prevents the paper from offering the sort of dispassionate, critically searching discussion the subject demands.

Even as the paper takes hits for its alleged liberal bias, it retains a supremely undeviating affinity for the cultural habits of the rich and celebrated ? most obviously in its Sunday Vows section, which features short celebratory biographies of newly consummated mateships from the overclass. The Sunday Styles section ? along with the Home and Dining sections, the T: Style magazine, and the recently added Thursday Styles ? delivers breathless dispatches on the mores, tastes, status worries, and modes of pecuniary display favored by the coming generation of anxious downtown arrivistes.

So the many installments of "Class Matters" ? a now nearly completed work in progress ? come across less like an authoritative exercise in social criticism than like an oddly anxious series of Tourette?s-style asides, desperately sidestepping the core economic inequities that the Times can never quite afford to mention outright. Getting the New York Times to explain the real operation of social class in America is, at the end of the day, a lot like granting your parents exclusive license to explain sex to you: there are simply far too many conflicts that run far too deep to result in any reliable account of how the thing works.

YOU CAN SEE the trouble early on, in what serves as the series?s mission statement: the pledge, in the May 15 first-installment "Overview" piece by Janny Scott and David Leonhardt, that they will chart the way "class influences destiny in America."

For most people on the receiving end of class prerogatives in this country ? unskilled service workers who find it all but illegal to form unions, say, or poor black voters in Ohio and Florida ? there?s no "influences" about it: class is destiny in America, delimiting access to basic social benefits like health care, education, job training, and affordable housing. Yet for all sorts of painfully self-evident institutional reasons, the New York Times can?t afford to approach a subject this potent in a straightforward fashion.

Instead Scott and Leonhardt marshal their readers through a leisurely tour of hoary American social mythology. America, they purr, "has gone a long way toward the appearance of classlessness" ? meaning, one supposes, that the downwardly mobile middle classes are actually thriving on the appearance of being in possession of wealth and disposable income, as though, by analogy, it would have been perfectly acceptable to report design upgrades in segregated Southern drinking fountains as a meaningful advance for black civil rights. "Social diversity," they explain, "has erased many of the markers" separating the country?s haves from the have-nots. Yet they fail to recognize that a more socially diverse ruling class remains a ruling class, after all ? an uncomfortable truth easily overlooked when one is writing for an influential organ of said ruling class.

Not surprisingly, then, the closer Scott and Leonhardt circle toward the heart of the matter ? how some Americans leverage social advantage into greater wealth and privilege, and how many, many more have seen wealth, educational opportunity, disposable income, and job security stagnate or decline while household debt and health-care costs soar ? the more ungainly and vague everything becomes. Still, Scott and Leonhardt are forced to concede a stubborn social fact: "Americans are arguably more likely than they were 30 years ago to end up in the same class into which they were born."

Here the dogged reader is at last primed to reckon with a sharp point of analytical departure: the storied American Dream of social mobility across generations appears to be stalled. Instead, however, the authors lurch into more bootless mythmaking: "Merit has replaced the old system of inherited privilege.... But merit, it turns out, is at least partly class-based. Parents with money, education, and connections cultivate in their children the habits the meritocracy rewards."

Well, no. Parents with connections, education, and money place their considerable resources directly at their offspring?s disposal. What results has everything to do with openly legible lines of power, and very nearly nothing to do with the cultivation of meritocracy-pleasing behavioral "habits" ? as any cursory glance at the Oval Office?s present occupant or the cast of The Simple Life will instantly confirm.

Meritocracy is an especially obtrusive and unstable term here, since neither Scott nor Leonhardt ? nor scarcely any uncritical champion of meritocracy in our time ? pauses to note the original meaning of the term. The concept of meritocracy first surfaced in a 1958 satirical political novel, The Rise of the Meritocracy, by old-line British socialist Michael Young. Young?s coinage was not intended to describe a system of impartial upward advancement, but rather the diametric opposite: a dystopian social order wherein bureaucratic rank outstripped wealth and title as the measure of human advancement. The irony in Young?s book, of course, was that the egalitarian nomenclature of this brave new order ? of which the word meritocracy was itself a prime example ? masked a system of spoils and rewards that was fast becoming much less fair and balanced than the old British class society it was thought to have supplanted. Only in America ? or more precisely, only in the A section of the New York Times ? could a bitter term of Old World satire gain traction as a straight-faced descriptor of a sunny status quo.

NOT SURPRISINGLY, the twinned notions of Right Conduct and Meritocratic Worth have shaped every subsequent installment of "Class Matters." The first reported piece, by the redoubtable Janny Scott, explores the consequences of unequal access to quality health care, by reconstructing three heart-attack cases ? affecting, in socially descending order, a well-heeled architect, an electric-company office worker, and an immigrant Polish maid. This comparative exercise does a pretty good job ? how could it not? ? of showing what happens when the basic right to critical health care is submitted to the market?s less-than-tender mercies.

Until, that is, Scott joins the hapless maid on a grocery-shopping junket and loses all patience: "Cruising the 99 Cent Wonder store in [Brooklyn?s] Williamsburg, where the freezers were filled with products like Budget Gourmet Rigatoni with Cream Sauce, [the maid, Ms. Gora] pulled down a small package of pistachios: two and a half servings, 13 grams of fat per serving. ?I can eat five of these,? she confessed, ignoring the nutrition label. Not servings. Bags."

Not servings, people! Bags! When Times scribes are reduced to sentence fragments, you know their patrician forbearance is running dangerously low. And how can you blame them, considering that the pistachio episode follows a sobering litany of other trespasses? When first stricken with her heart attack, Gora dismissed her husband?s suggestion that she was seriously ill and needed an ambulance, and instead tried to collect herself with a glass of vodka; against explicit doctors? advice, she sneaks cigarettes and doughnuts, and even clips a cockamamie diet from a Polish magazine that permits her to eat generous portions of fried food and steak. And so Scott?s telltale moment of exasperation carries an unmistakable subtext: There?s just nothing to be done with these people. Never mind that Gora?s behavior suggests that she is also suffering an extended, and completely understandable, bout of depression ? an all-too-common health affliction among the working poor. Why extend anything like universally available health care to a group of people so willfully perverse?

Likewise, the next series installment, on marriage and class, completely neglects the subject?s most historically significant recent development: how more affluent mates postpone marriage and childrearing through what?s known euphemistically as "assortative mating" (i.e., the sort of closely vetted, intraclass pairings of the privileged featured every week in the Vows section of the Times), versus the considerable pressures within poor communities to marry early and procreate often. Instead, the main dispatch by Times reporter Tamar Lewin sets up elaborate social quandaries better suited to a Victorian novel than to 21st-century American life. It describes the course of a second marriage for both partners that?s taken them beyond the reach of their familiar social stations: wife Cate Woolner is a rich heiress, husband Dan Croteau is a working-class car salesman. It?s hard to suss out just what the social lesson of such a plainly atypical union is supposed to be. Apart, that is, from the manifest truth that, left to their own devices, the rich will always raise the most irritating children on earth ("[Woolner?s son] Isaac fantasizes about opening a brewery-cum-performance space, traveling through South America, or operating a sunset massage cruise on the Caribbean").

By Sunday, May 22?s entry, a piece by Laurie Goodstein and David Kirkpatrick on the evangelical mission called the Christian Union, which is targeting the Ivy League elite, the Times reverts to full-on barbarians-at-the-gates-style culture alarmism. The piece is not even, in any clear way, about social class (at least not the destiny-inhibiting type adumbrated in the series?s mission statement), since Matt Bennett, the principal force behind the Christian Union, is heir to a Dallas-based hotel empire, and the one quasi-needy case in the piece, a sophomore missionary at Brown named Tim Havens, rather inconveniently declares himself pre-med by the story?s end. And what is clearly meant to be a spit-take moment for Sunday-morning Times coffee drinkers ? Bennett?s claim that God came to him in a vision and "was speaking to me very strongly that he wanted to see an increasing and dramatic spiritual revival in a place like Princeton" ? actually makes a good deal of sense when one recalls (as Kirkpatrick and Goodstein apparently do not) that Princeton was the intellectual capital of American fundamentalist theology in the early part of the last century. The reporters do mention briefly that most Ivy League schools in fact began life as "expressly Christian," but dwelling too long on such facts would clearly contradict the piece?s half-baked social premise: that newer, and traditionally down-market, evangelical faiths are now storming the citadels of American intellectual privilege.

For May 24?s installment ? the midpoint entry in the series ? Leonhardt offers a predictably baffled piece on the most perverse of working-class mores: the refusal to attend college for full four-year terms. Leonhardt telescopes this chilling trend through the saga of Andy Blevins, a 29-year-old produce buyer for a big-box retail warehouse in small-town rural Virginia. Blevins dropped out after his freshman year at Radford University; he plans to return to school part-time, though, in order to earn a degree and teaching credentials in elementary education, even though the vast majority of returning college dropouts never complete their degrees. The overall high failure and dropout rates among America?s poor and working class admit to no "simple answer," Leonhardt writes. There is, to be sure, the vulgar question of money, he notes. Tuitions that routinely outstrip the rate of inflation, and the specter of contracting long-term five- or six-figure loans, are strong, sobering deterrents.

For Leonhardt, however, economic inequality can provide only a glancing explanation of class inequities ? culture has to be where the real action is. After ticking off the formidable financial obstacles posed by higher education, Leonhardt primly announces that "the deterrents to a [college] degree can also be homegrown. Many low-income teenagers know few people who have made it through college. A majority of the non-graduates are young men, and some come from towns where the factory work ethic, to get working as soon as possible, remains strong, even if the factories themselves are vanishing. Whatever the reason, college just does not feel normal." It?s worth noting that such cultural delicacy did not seem to prevent FDR from signing the GI Bill into law, thereby dispatching the largest-ever contingent of working-class American men to elite university campuses. There was little apparent fuss about how these entering students processed their unfamiliar cultural surroundings, once the federal government brought tuition costs into reasonable alignment with their living standards.

Nonetheless, the paper of record, with its condescending cultural exoticism, once again dwells lovingly on behavior and culture rather than on cold economic facts. Leonhardt mentions the gruesome inequity that, thanks to the Bush administration?s recent cuts to the Pell-grant program, "high-income students, on average, actually get slightly more financial aid than low-income students." But apart from some vague discussion of the emerging vogue for need-conscious class-based affirmative action, he can?t connect the obvious dots here: that without universal, federally funded support, the prospect of a full tour in the world of higher education ranks somewhere alongside winning the lottery in the pantheon of plausible working-class life outcomes.

Instead, Leonhardt frets on and on about the boneheaded call the 19-year-old Blevins made when he dropped out, and the extreme unlikelihood, despite the guy?s professed best intentions, that any good will come of his pitiful bid to reinvent himself. And should the wall-eyed voyeurism of the piece leave any doubt, the front-page photo speaks volumes: it shows Blevins indolently sprawled on his living-room sofa, gaping at a football game on TV, while keeping a bottle shoved in the gullet of his three-year-old son, Luke, whose head dangles perilously over the edge of the couch. This, the casual reader is urged to conclude, is just the sort of layabout behavioral pathology that keeps working-class families from achieving serious upward mobility. Yet the text makes clear that Blevins doesn?t have a great deal of time to devote to semiconscious gridiron gawking, since he routinely works six-day weeks, at shifts of 10 hours or more. This image, like most feature subjects in "Class Matters," seems clearly intended to trigger a quiet shudder of patrician thanksgiving that Times readers really do not go there but for the grace of God.

SUBSEQUENT SERIES installments perform the same reassuring alchemy, transmuting the raw stuff of material deprivation into judiciously arm?s-length cultural perplexity. A May 25 dispatch on immigrant-laborer tensions at Uma Thurman?s favorite diner trails off into puzzlement over how immigrant managers resist unionization of other immigrant workers in their employ. (Don?t they know that social diversity abolishes class distinction? That a Greek restaurant owner is supposed to embrace his Latino busboys and waitstaff in a gorgeous mosaic of service-economy unity?) Another blowout Sunday entry, on May 29, found the Times returning with palpable relief to a subject on which it wields genuine authority: how and why luxury shopping is failing to perfectly mirror hard-core American socioeconomic divisions. Jennifer Steinhauer registers the perfect ruffled tone of disbelief as she reports on the decline of true luxury consumption in America, as more middle-class people get into deeper debt to make high-end purchases like cruises and designer chocolates. For a paper that routinely lavishes acres of adoring prose on the shopping preferences of the fabulously well-to-do, this sort of news has roughly the same effect that Andres Serrano?s Piss Christ photograph exercised on the Catholic League: "Rising incomes, flattening prices, and easily available credit have given so many Americans access to such a wide array of high-end goods that traditional markers of status have lost much of their meanings." For devout Times scribes, this, truly, is the world turned upside down. An unintentionally hilarious graphic accompanying the main body of the piece ? "Swells and Ne?er-Do-Wells: A Class Timeline" ? echoes the same clear longing for the snappy, superficial navigation of social distinction. Here is one of its final bullet points: "1989: The Berlin Wall falls. Marxism?s vision of a classless society is out; global capitalism is in."

There you have it: a watershed moment in modern democratic revolution worded in the style of an America Idol ballot. Don?t dare remind our glib Times editors that Marx himself foresaw the triumph of global capitalism as the precursor to his vision of a classless society. They?re telling you what?s in, and there could be no more fitting final word on the subject from a journalistic oracle of the Times? stature ? except, that is, to turn from all this messy, unresolved class nastiness to the crisp and clean business-as-usual digests in the Sunday?s Vows column.

Chris Lehman is a writer based in Washington, DC, and author of Revolt of the Masscult (Prickly Paradigm, 2003). He can be reached at lehmannchris@mac.com

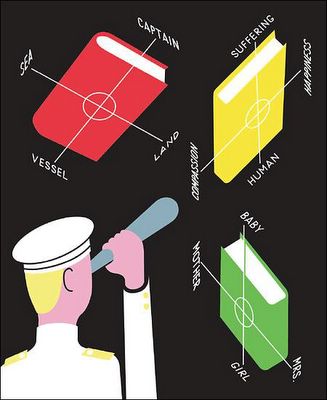

Richard McGuire

June 5, 2005

The Word Crunchers

By DEBORAH FRIEDELL

In David Lodge's 1984 novel, ''Small World,'' a literature professor fond of computer programming presents a novelist with a fantastic discovery: by entering all the novelist's books into a computer, the professor can determine the novelist's favorite word. The computer knows to ignore the mortar of sentences -- articles, prepositions, pronouns -- to get to ''the real nitty-gritty,'' Lodge writes, ''words like love or dark or heart or God.'' But the computer's conclusion causes the novelist to shrink from ever writing again. His favorite word, it finds, is ''greasy.''

Two decades later, Amazon.com, improving on its popular ''search inside the book'' function, in April introduced a concordance program, whereby a click of the mouse reveals a book's most frequently occurring words, ''excluding common words.'' Further clicks reveal their contexts. And so we learn that the nitty-gritty words appearing most frequently in the King James Bible include ''God,'' ''Lord,'' ''shall'' and ''unto.'' The word that appears most frequently in T. S. Eliot's ''Collected Poems'' is ''time'' -- ''There will be time, there will be time'' -- while the word that turns up most frequently in ''Extraordinary Golf,'' by Fred Shoemaker and Pete Shoemaker, is, illuminatively, ''golf.''

Such computer tools have been centuries in the making. As the legend goes, the first concordance -- of the Vulgate, completed in the early 13th century -- required the labor of 500 Dominican friars. Even in more modern times, those who began concordances knew that they might not live long enough to see them completed. This was the case for the first directors of the Chaucer concordance, which took 50 years before reaching publication in 1927.

In order to speed the process for his Wordsworth concordance, first published in 1911, the scholar Lane Cooper required an army of Cornell graduate students and faculty wives. It was a laborious undertaking, involving glue, rubber stamps and a vastly intricate system of cross-referenced 3-by-5 cards.

At the same time Cooper was mapping ''The Prelude,'' biologists at other universities were discovering sex chromosomes. Indeed, in his description of the alphabetization and arrangement involved in concordance-making, Cooper calls to mind a profession that was only just beginning to exist. He is a geneticist of language, isolating and mapping the smallest parts with the confidence that they will somehow reveal the design of the whole.

In 1951, I.B.M. helped create an automated concordance that cataloged four hymns by St. Thomas Aquinas. The scanning equipment was primitive. Words still had to be hand-punched onto cards, programs for alphabetizing had to be written, and many found the computers more trouble than they were worth. Even with electronic assistance, indexing all of Aquinas took a million man-hours and 30 years before it was finally completed in 1974.

Yet even as computers grew more sophisticated, some scholars resisted them. In 1970, Stephen M. Parrish, an English professor, described how when he ''proposed to some of the Dante people at Harvard that they move to the computer and finish the job in a couple of months, they recoiled in horror.'' In their system, ''each man was assigned a block of pages to index lovingly,'' and had been doing so contentedly for more than 25 years. But eventually, of course, concordance makers joined the ranks of all the other noble occupations gone.