Saturday, June 04, 2005

California Coastal Commission

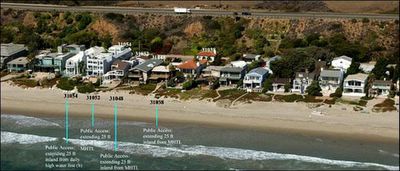

This land is my land: A state guide for sunbathers to Broad Beach in Malibu, showing how close the public can come to private property.

June 5, 2005

In Malibu, the Water's Fine (So Don't Come in!)

By MIREYA NAVARRO

MALIBU, Calif.

LAST Monday, two white wooden doors swung open for the first time onto Carbon Beach, courtesy of David Geffen, the DreamWorks co-founder, who owns a large shingled compound on the ocean and has the option of borrowing suntan lotion from billionaire neighbors like Eli Broad and Haim Saban. The mile-and-a-half-long beach, among the first glimpses of Malibu on the drive up from Los Angeles, is public by law, but to get to it, visitors must find a way to penetrate a wall of multimillion-dollar homes.

The famous Malibu coastline, the stuff of surfer lore and "Gidget" movies, is a battleground that heats up every summer. This year, the score is 1-0 in favor of the underdog: the beachgoer who appreciates exclusive comfort but can't afford it.

Mr. Geffen had agreed to allow a pathway to run alongside his property in 1983 in exchange for state permission to add a swimming pool and other expansions. But in 2002 he filed a lawsuit to fight the public's right to gain access to the beach at that spot. Earlier this year he relented.

Cameron Wellwood, 36, a guitar player in a band called the Harsh Carpets, was one of the first to pass through Mr. Geffen's gate.

"I can just come from across the street," said Mr. Wellwood, who lives on the oceanless side of the Pacific Coast Highway. "It just makes things so much more pleasant."

Before, to reach the waves just steps from his apartment, he had to walk two miles round trip to use another entry point.

He deemed the opening of the Geffen gate "monumental," which among Southern California beachgoers is no exaggeration. They contend with rules so confusing and restrictive that state officials and public interest groups have come up with maps to help people figure out where to walk or plop down their towels and umbrellas without disturbing homeowners.

The tension over space ricochets along Malibu's 27-mile coastline, where the homeowners include Steven Spielberg, Pierce Brosnan, Courteney Cox, Jeffrey Katzenberg and Richard J. Riordan, the former mayor of Los Angeles.

The homes are closed off on the street side, but the ocean side affords a democratic access that makes some of the famous dwellers nervous. The beach houses usually feature walls of windows facing the water, with open decks or expansive patios. Some owners, like Mr. Geffen, have their own guards and security cameras.

"One thing is not to want the public on the beach, but there's no excuse for not sharing the beach with your neighbors," Mr. Wellwood said as he took in the salty air.

"This is so typical of Malibu," he added.

The city, which joined Mr. Geffen in his lawsuit, is an epicenter for beach conflict, said officials with the California Coastal Commission, which regulates the use and development of the coast. The disputes here, however, tend to involve not drunken brawls and bad volleyball calls, but the tug between the public and the private interest.

Similar tensions are found in wealthy enclaves on both coasts, but in Malibu, which has 13,000 residents, they come with the complications of dense development, expensive real estate and a high celebrity quotient. Where else would you expect to stroll a few yards from Mel Gibson at a gathering with a group of nuns on a beachfront deck, or to bump into Mr. Spielberg walking along the water, as barefoot eyewitnesses claim to have done?

Some residents of Broad Beach, which is north of Carbon, up the Pacific Coast Highway, say they welcome visitors. But the homeowners' association puts up dozens of No Trespassing signs on the sand and hires patrols in all-terrain vehicles to keep people off private property in the summer.

"I'd be intimidated," said Lisa Haage, the chief of enforcement for the California Coastal Commission, which is negotiating a compromise with the homeowners' group. "When you go to the beach you want a happy day; you don't want armed conflict."

Made to feel as if they are crashing an A-list party, visitors to Broad Beach have been confined in the past to sitting in the narrow strips off two access ways, to play it safe. Yet many seek the hard-to-get-to beaches for the same reason some homeowners pay $5 million to $45 million for their properties: privacy.

Because it is often assumed that these beaches are off limits - and because of impediments like limited parking - crowds are often thin. There is none of the bustle of nearby Zuma Beach and other public beaches, which offer parking lots, food shacks and restrooms.

Dhana and Matthew Gilbert and their 14-month-old daughter, Riley, live in Pacific Palisades, a coastal community with its own beaches and celebs, including Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger. But in the summer they drive 45 minutes up the Pacific Coast Highway for the quiet of Broad Beach, parking on the street near the access way.

"This feels like vacation," said Mrs. Gilbert, 37, a film production coordinator, who sat with her family under a blue umbrella last weekend near the sand dunes that shield some of the homes. "It's private. No music. It's cleaner."

But gazing out from his second-level terrace off the master bedroom, Marshall Grossman, an entertainment lawyer, was hardly as content as the Gilberts. He could see a woman and her dog crossing into his next-door neighbor's invisible property line.

"This woman here is clearly on private property," Mr. Grossman said. "If she were in Zuma Beach she'd be ticketed and her dog impounded."

Mr. Grossman, who is part of the 100-member homeowners' association and a former coastal commissioner, said the anxiety among neighbors is based on the behavior of a minority of troublemakers: strangers brazenly ensconced in lounge chairs and patio furniture belonging to homeowners; people who come with dogs or on horseback and fail to clean up after their animals; paparazzi who pretend to be surfers or dog walkers to sneak their shots; and fans looking for celebrities.

Some interlopers have even been caught taking showers, using the swimming pool or sleeping on a sofa in private homes, Mr. Grossman and other neighbors said.

"It's a little bit of a challenge," said Mark Attanasio, the owner of the Milwaukee Brewers, who ran into Mr. Grossman sometime later on the sand in front of Mr. Attanasio's 1940's Cape Cod-style cottage.

"If I went to their house and sat in their backyard, they wouldn't be pleased," Mr. Attanasio said. But Mr. Attanasio's backyard, so to speak, abuts the Pacific Ocean, an A-list attraction itself.

In general, visitors must stay within the mean high tide line. The rule of thumb is wherever the sand is wet, it is public. But the tide line that divides public from private moves every day.

To complicate matters further, some property owners, like Mr. Geffen, have allowed extra access beyond tide lines, from 25 feet to about 100 feet of dry sand in some cases, as part of agreements with state officials.

Some compromises meant to simplify the enforcement of the boundaries are in the works. In the meantime, at Carbon Beach, Access for All, the nonprofit group that waged battle with Mr. Geffen, is providing monitors and maps to explain the rules of the new access way to visitors.

"We're looking for a working relationship," said Steve Hoye, the director of the group. "If we have to be here with a tape measure, we'll have problems."

Andy Spahn, a spokesman for Mr. Geffen, said Mr. Geffen had no comment. But some of his neighbors said they had no problem with the idea of sharing the beach with more people.

"I do enjoy seeing people walking down the beach," said Dian Roberts, 78, who lives several doors from Mr. Geffen. What she did not appreciate, she said, was the portrayal of the Carbon Beach access conflict as a case of poor versus rich.

"I'm not rich," said Mrs. Roberts, who said she bought her land more than 50 years ago for less than $5,000, then spent an additional $20,000 building the house where she and her husband raised four children. "I just happen to have a house worth a pile."

Richard Terry, one among dozens of paparazzi who prowl the Malibu beaches looking for their next celebrity magazine shot, said star sightings were plentiful. He recently got an assignment to shoot a barbecue at Danny DeVito's house on Broad Beach and on his way there happened upon Dustin Hoffman riding a bicycle.

A few hours later, as if on cue, Amanda Carr, 18, a tourist from New Jersey, sauntered through the access way with a friend carrying multicolored beach towels. She said to Mr. Hoye, who stood at the entrance: "I want to see Britney Spears's house. Do you know where it is?"

Not on Carbon Beach, she was told.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Contact Us Back to Top