Wednesday, June 08, 2005

The University of Maryland pool where Roberto Cabrera practices has underwater speakers, but he prefers listening instead to his waterproofed iPod

Go-Go-Go Beat

From Elevator to Anywhere, There's No Stopping the Music

By Linton Weeks

Washington Post Staff Writer

Wednesday, June 8, 2005; C01

Roberto Cabrera is a self-professed iPod addict. On this recent weekday afternoon, Cabrera, 22, is at one of his favorite hangouts, the Atlanta Bread Company in Greenbelt, doing some artistic sketching and listening to Billy Idol and the British popsters Pulp on his 20-gigabyte iPod. He's dark-haired, dark-eyed, slightly mustachioed and built compactly. The telltale white wires, tentacling down from his earbuds to his small white digital music player, connect Cabrera to the more than 5,000 songs that he has downloaded from CDs and the Internet.

To get a sense of how much music that is: Assuming that you listen to an hour's worth of tunes a day and each song lasts an average of four minutes, you would spend about a year exhausting the playlists on Cabrera's iPod.

Music addict Cabrera, however, listens to 14 hours of music a day. He needs two iPods -- so that one can be charging at all times.

A junior international business and studio art major at the University of Maryland, the amiable Cabrera says that music is a mega-massive part of his life. "I've always been influenced by music," he says. Now he needs it "all around me, all the time."

He chooses hard-chargers (99 All Stars or Andrea Doria) to wake to, softies (Cafe del Mar) to study by, inspirational bands (Snow Patrol or Nickelback) to exercise to, and mind-massaging performers (John Mayer or Radiohead) to help him drift off at night. He says simply, "I cannot go to sleep without music."

A freestyler on the Terrapins swim team, Cabrera packs his own tunes -- with the help of a waterproof device and headphones -- while practicing at the University of Maryland pool, which already has underwater speakers piping music to swimmers.

He listens to music of his own choosing while: eating, running, painting, pumping weights, driving. He listens to music while giving directions to someone on campus. He even listens to music in the classroom. "Like if it's a history course," he says, "I really could care less. The teacher is talking in a monotone. I turn it up. I put in one earbud and turn my head a little and the teacher can't tell."

All day, every day, Cabrera sets his waking hours to music. He is, in effect, creating the soundtrack of his life.

He is a musicholic and a classic creation of our time: the Era of the Ear, the Epoch of Omnipresent Song, this miraculous Age of Ubiquitous Music.

Surrounded by Sound

It's everywhere. There's no escaping it. Via broadcast and satellite radio and TV, an ever-expanding array of recording technologies -- such as CDs and MiniDiscs -- and the Internet, music has invaded the tiniest, quietest corners of our lives. You hear it in grocery stores, dentist's chairs, on TV commercials, whenever there's a lull in the action at sporting events, in bookstores, on the telephone while on hold, in the background while disc jockeys are talking, at restaurants and health clubs and gas stations.

We can hear the percussive candombe of Uruguay, the eerie throat-singing of Mongolia, raucous bush songs of the Australian outback, Gwen Stefani belting out "Hollaback Girl," or Mississippi John Hurt fingerpicking his blues guitar at any time, any place or any volume we choose.

Online music stores such as iTunes and Napster offer hundreds of thousands of songs for the downloading. Countless new bands spring up all the time, many producing tired music. Meanwhile, old bands refuse to fade away, reuniting ad nauseam for PBS concerts and producing more tired music. And TV music shows -- like "American Idol" -- spawn even more tired music.

But wait, there's more. Nascent and aggressive satellite radio companies advertise a whole new explosion of music possibilities. Sirius promises 65 channels of music; XM offers 67. Oakley's Thump sunglasses contain a tiny digital music player, and cell phones everywhere ring to the opening bars of "Stairway to Heaven."

Music is a luxurious necessity. "There has never been a human culture existing or extinct that has not had music," says Mark Tramo, a neuroscientist at Harvard Medical School who believes that music is a universal language.

Certain melodies inspire, arouse, invigorate. Others provoke, insult, infuriate. As we've learned from watching decades of movies and TV shows, effective music can move us to tears and to cheers. It pumps up the color and texture of reality; the mundane morphs into art. We subconsciously listen for resolution in music, the way we naturally yearn for color-wheel answers in paintings and solutions to well-written mysteries.

Music can be oh so social -- uniting us, family-like in a harmonious unbroken circle of fellowship. "We Are the World" comes to mind. Music can also be divisive, serving as a wedge between cultures or genders. The misogynist "Superman" by Eminem, for instance. Ever since the first Walkman appeared in 1979, social scientists have railed against the alienation caused by personal music devices. And other scientists have warned us of the inevitable deafness and cerebral distraction.

We consume music and music consumes us. We are caught in the middle of a musical war. Whole industries are built on dumping music upon us, while others allow us to choose the music we want to listen to. The armies can be divided into those that overpower and those that empower. It's a battle royal for our ears, our brains, our bank accounts. As a result, never before has there been so much music -- good, bad, harmonic, atonal -- available.

As composer Libby Larsen puts it, "Recording technology has made us all digital democrats." Music today is free-flowing, intoxicating, addictive, and it's no wonder that some people, like Cabrera, just can't get enough of it.

Music on the Brain

They are -- Cabrera and his ilk -- the musicholics: disengaged folks with small, sleek digital players in their hands or pockets who, to varying degrees, need music like they need oxygen. They carry CD players and MP3 gadgets. Many depend on Apple iPods: 10 million have been sold since the device was introduced in November 2001. And there are more and more portable satellite radios and music-playing cell phones showing up on store shelves every day to feed the musical habit.

They are people like:

? Demisha Camp, 21, in a T-shirt and bluejeans, strolling through the Fashion Centre at Pentagon City. She's on her way to a hair salon where she works as a shampooer. She's listening to Faith Evans on her CD player. "I have to work with music," she says. "I can't focus without music or sound."

? Marsha Guery, 20, on the Green Line headed toward Howard University, where she is a fashion merchandising major. She's communing with Amarie on her Sony MiniDisc player. She likes to have music on all the time. Her parents often say to her: Get that music out of your ears! You're not paying attention! But she likes the feel of the sound. "When I walk down the street," she says, "I'm in my own little world."

? A woman in silver slippers at a back table in the upper Georgetown Starbucks. She is studying for a science exam and listening to music on her compact disc player. She loves to listen to music while doing other things, she says. On the table, a paperback textbook lies open. There is a full-page diagram of the human brain.

So apropos. The music, the brain, Starbucks.

Music is arguably the quickest, most immediate mass cultural auger into the brain. Sound streams through the ears to the auditory cortex, which links directly to the limbic system, the emotional clearinghouse. In a fraction of a second, your hearing's job is already accomplished. Then the mind and imagination take over. The sound is reshaped into more abstract representations of music. It conjures up notions of pleasure and displeasure, of desire and dissatisfaction, of memory and long-lost tinglings.

Neurologist Richard Restak says this pinball effect in the brain explains music's transcendence and power. It can "evoke an extremely intense experience," he says.

Neuroscientist Tramo says the research suggests that "all of us are able to apprehend music, that we 'get it' and that we can be manipulated by it."

And this explains why neuro-marketers -- lab-coated people who study the sweat patterns and heart rates of consumers under various circumstances -- are deeply intrigued by music's effects and how they can be used to manipulate us by the rhythm of a piece, the rise and fall of its structure, certain chord changes.

Sonic Sales Strategies

One of the new-school companies on the edge of manipulation-by-music is also one of the old-school originators of the idea.

Muzak, a name synonymous with syrupy, go-nowhere elevator music, has reinvented itself to take advantage of music's useful ubiquity. As we sift through the ever-expanding global jukebox to put together the soundtracks of our lives, Muzak -- along with firms such as DMX and Audio Environments -- is only too happy to help.

From its founding in 1934, Muzak has nearly always been ahead of the curve -- technologically and psychologically -- and its history tracks the ever-widening wash of available music.

In 1937 a couple of British psychologists asserted that music increased worker efficiency, and the idea of using it to bring order into the chaotic noise of factory machines really took off. According to the corporate Web site, Muzak.com, "World War II resulted in great growth for Muzak. As the whole country geared up for production, Muzak took a leading role in work-related music. Time and again, industrial psychologists found music improved morale, attendance and production." Soft Muzak was piped into offices and stores all across America.

In the late 1990s, Muzak reinvented itself into a New-Agey "experiential-branding" concern. The company shifted its focus from background music to foreground; all of a sudden the music wanted to be noticed, to work its influence on you, to implant "earworms" -- slang for musical phrases you can't get out of your head -- into the disc changer of your brain.

Today the South Carolina-based company has 3,000 employees and some 350,000 clients, including some abroad. About 100 million people undergo a Muzak attack every day. And Muzak pushes a high-concept plan called "Audio Architecture, " which means that Muzak would like to help companies use the emotional power of music to sell more products.

Audio Architecture is emotion by design, says Muzak's director of corporate communications Sumter Cox. "We are all about the future," says Cox, "and really what our product does is create an experience. We are a branding company."

Nearly every retail shop, he explains, has a logo and a certain look. Muzak wants to put a musical face on the place. Muzak consultants sit down with companies like Applebee's and LensCrafters and listen to their ideas of what they want to communicate about their brand image. Do they want to be perceived as macho or feminine, young or old, country or urban? Muzak then selects a specialized music program that helps "tell" the company's "story" and, as a result, enhance the consumer experience. The song list for Red Lobster, for instance, contains music that "embraces customers and makes them feel cared for and loved." The Muzak playlist includes Marvin Gaye, Sade and Simply Red. For LensCrafters, Muzak found music that exudes "assurance and independence," such as that of Norah Jones and Sting.

Popeyes fried chicken franchises are pre-wired with zydeco and upbeat rock. In these joints you can hear a cheery-voiced singer singing, "You're paying now, but it's all right!"

For some companies, such as Old Navy, Muzak sets up each store's sound system -- Klipsch speakers, Bose amps, etc. The "energy flow," Sumter Cox says, "is supposed to be a smooth consistent experience." An automatic timer lowers the volume in the morning hours and cranks it up for the midday onslaughts.

At lunch hour, the Aeropostale shop in the Fashion Centre at Pentagon City is resonating. Very loudly. A chain of ultra-casual clothing stores, it is one of Muzak's customers. Patrons, mostly young women, flit in and out of the shop like sparrows. Through the speaker system, the British duo appropriately named Frou Frou sings a light, airy "Must Be Dreaming." Nearby there's disco music at Sephora. Hip-hop at Up Against the Wall. Rap music bursts out of a kiosk selling XM Satellite Radio subscriptions. More music rains down from overhead speakers in the corridors. Cacophony rules.

Starbucks, with a small shop in the food court, is hoping to provide more and more music for your personal soundtrack. The Seattle-based coffee company reported in late May that it had sold 21,000 copies of Antigone Rising's "From the Ground Up" in 12 days from 4,400 U.S. stores.

Some of the businesses not only have tunes playing overhead but specially packaged music for sale. Williams-Sonoma sells its own CDs -- in a wall bin near the cutlery -- including one to play while you're eating dinner. Victoria's Secret has a rack of "road trip" CDs on its checkout counter. The Godiva shop offers, no kidding, a $12.99 disc titled "Melt: Music to Eat Chocolate By."

An Island of Sound

There is far too much music in the world, the late composer Virgil Thomson wrote in London Magazine. "I do not feel this because I get tired of musical sound itself. Musical sounds are always a pleasure. It is unmusical sounds masquerading as musical ones that wear you down, and the commercializing of musical distribution has given us a great many of these as a cross to bear. It has also given such currency to our classics that even these the mind grows weary of. Because though musical sound is ever a delight, musical meaning, like any other meaning, grows stale from being repeated."

He wrote that in 1962. Imagine how he would feel today in the halls of the Pentagon City mall.

Milan Kundera, author of "The Unbearable Lightness of Being," writes that public music today has become "a flood of everything jumbled together" so that we don't know who composed it or when it begins or ends. It is "sewage-water music in which music is dying."

Neurologist Restak is sometimes overwhelmed. He rails against bookstores, for instance, that play loud, incongruous music. "They'll have something on there by the Doors," he says. "I can't look at a book in that situation."

As for shopping in the supermarket to Beach Boys music, Restak says, "To me it's dissonant. There is an emotional disconnect, a physical disconnect."

Music is fire. It can be warm and comforting. Or it can spread fast and move dangerously through the landscape. The musicholics have learned to fight fire with fire.

At the Georgetown Starbucks, as the silver-slippered woman listens to a CD while studying the brain, she is apparently oblivious to another layer of music in the caffeinated air -- the misty sounds of Antigone Rising.

At the Greenbelt Atlanta Bread Company, musicholic Roberto Cabrera listens to the technopoppish Rasmus on his iPod as he waits for his lunch. Overhead Muzak's classical music plays.

And when he goes to a mall and shops at Abercrombie & Fitch or Urban Outfitters, where music can be bursting through giant speakers, shaking the room and pressing on the chest as the stores and the corporations and the philosophies infiltrate his ears and seek out the tiniest, quietest corners of his life -- he likes to wear his iPod.

That way he gets to listen to the music he wants to, while walking at the pace he wants to, while choosing the polo shirts and jeans he wants to buy. And, he says, there is added value: Salespeople leave him alone.

? 2005 The Washington Post Company

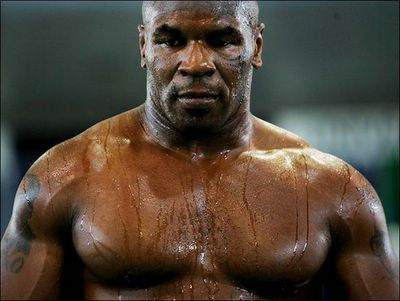

Pablo Martinez Monsivais/AP

Almost 39, Mike Tyson is seeking a new chance in the ring. Tuesday his sweat formed a puddle.

June 8, 2005

Tyson Enters the Fight of His Life

By CLIFTON BROWN

WASHINGTON, June 7 - After a brief but vigorous workout Tuesday, Mike Tyson sat on a stool and uttered a favorite expression that has been used to describe his career and his life.

"Old too soon, smart too late," he said.

Tyson desperately hopes that it is not too late.

Facing his 39th birthday on June 30, after serving a prison sentence for rape and after pitfalls that have included declaring bankruptcy, biting off a portion of Evander Holyfield's ear, and marrying and divorcing twice, Tyson is trying to resurrect his career - again.

Needing a victory to restore his credibility as a heavyweight contender, he will face the unheralded Kevin McBride (32-4-1) on Saturday night at the MCI Center.

Though he no longer dominates in the ring and despite his many transgressions, Tyson maintains a magnetism that leaves sociologists struggling for explanations. Promoters said that more than 13,000 tickets had been sold for Saturday's bout, and it could be a sellout by the time Tyson enters the ring. Many thousands more will spend $44.95 to watch it on pay-per-view.

Love him or loathe him, it remains difficult to ignore him. But Tyson insists he has changed, that he has begun a long journey toward becoming a better person, and not just a better boxer.

"I don't want to be that guy anymore," Tyson said, talking calmly about his past while sitting in the locker room of Burr Gymnasium on the campus of Howard University. "I liked to humiliate people, because I had been humiliated. I wanted other people to feel the pain I felt as a child.

"There's another fight after this fight, the fight of life. I'm almost perfect in the fighting business, 50-5. But in the fight of life, I'm a pug. I'm a palooka."

Tyson was the palooka in his last fight, knocked out by Danny Williams in the fourth round last July 30.

"I was embarrassed to lose to a gentleman of his stature," Tyson said.

That fight exposed Tyson's lack of stamina and his defensive shortcomings, but with a new trainer, Jeff Fenech, Tyson said that Saturday would be different.

"I'm equipped to beat Kevin McBride," Tyson said.

After 10 weeks of training in Scottsdale, Ariz., where he lives, Tyson appears to be in decent shape. He moved well in the ring Tuesday, his heavily tattooed body had definition, his hand speed was evident as he threw crisp punches; a puddle of perspiration formed under his stool after he sat down. Those around Tyson hope that when he steps into the ring, he will look more like the Tyson of old, rather than an old Tyson.

"He likes Jeff, so he has trained," Shelly Finkel, Tyson's promoter, said. "At the beginning, he was throwing up and he was horrible. But as the weeks went on, we saw it coming together. Hopefully Saturday, we'll see it. Hopefully he'll get some fights under his belt, he looks good, he takes care of his debts and he ends up with something out of this sport. It's not the greatest heavyweight division right now. While we're in a division that has more than one champion, he can pick someone and maybe be champion again."

That is Tyson's plan, to beat McBride, to win another tuneup fight or two and to fight for a championship belt within two years. But how badly does Tyson want it? He certainly has motivation. After squandering almost $300 million and declaring bankruptcy in 2003, Tyson will be paid $5 million for this bout, and the more he wins, the more opportunity he will have to erase his debt.

In his prime, Tyson was among the most intimidating fighters ever, winning his first 37 fights, many of them by devastating knockouts. He won the World Boxing Council title from Trevor Berbick in 1986, knocking Berbick senseless in the second round; Berbick stumbled around the ring as if he were walking on a merry-go-round.

Perhaps the crowning moment of Tyson's career came in 1988, when he stretched out Michael Spinks on the canvas in 91 seconds, a performance in which Tyson lived up to his nickname, the Baddest Man on the Planet.

But Tyson was bad outside the ring as well, living in excess and behaving in bizarre fashion. It finally caught up with him in 1990, when he was knocked out by Buster Douglas in Japan in one of boxing's biggest upsets.

Less than two years later, Tyson was convicted of raping Desiree Washington in an Indianapolis hotel room, and he spent almost three years in prison.

Tyson took great pains Tuesday to emphasize that he had changed and that he did not want to be remembered for his many mistakes. Tyson has always been a contradiction, from his fits of rage to the Arthur Ashe tattoo on his left arm. But those around him sense a calm they never saw when he had a fat wallet and a fat entourage to go with it. Tyson even chastised a questioner Tuesday for using profanity and said that one of his main goals was to set a better example for his six children.

"I've gone through hard times under the microscope," Tyson said. "It's not about being the best fighter in the world or the worst fighter, it's about being a better person. I always took care of my children financially, but I never gave anybody my time."

Tyson hardly has time on his side when it comes to boxing. But in a sport that looks kindly on those who pick themselves up from the canvas, he seemed eager to take advantage of another chance.

"I've had 30,000 chances," Tyson said. "I don't want the chaos anymore."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Contact Us Back to Top

Chester Higgins Jr./The New York Times

June 5, 2005

Kicking Off Her Heels

By DAVID COLMAN

THERE is, of course, nothing like a stiletto. Spiky, dainty things, so complimentary to the foot and so alluring to the onlooker, they are so wildly uncomfortable for walking in the world that they function as a veritable badge of leisure.

Diane Von Furstenberg has been on the stiletto circuit longer than many, having embarked on an It Girl career some 30 years ago. She married Prince Egon Von Furstenberg. She invented the wrap dress. And she had so many licenses that even paper towels were scrawled with her signature. The 1980's were less, well, profitable. Today, married to her longtime friend Barry Diller, her dresses experiencing a heady revival and the Council of Fashion Designers of America presenting her with a lifetime achievement award tomorrow night, Ms. Von Furstenberg is standing glam and tall in heels again.

"Feet are so incredibly important," she said, like a character in Colette (the writer, not the store). "If I am going for a heel, the more uncomfortable, the better. You're going for attitude."

But stilettos will get you only so far ? like to a waiting Town Car. Which is why, when it comes to footwear, Ms. Von Furstenberg's favorite escape vehicle is a hiking boot. "I'm a Capricorn," she said. "I'm a climber. I'm a goat. I don't play tennis. I don't like arranged games. I like to do things where you can really go away. When you climb, you're silent."

Unlike those daring ladies who have scaled the Himalayas, Ms. Von Furstenberg does not go in for pitons, descenders and belay devices, being one of the garden-variety casual hikers whose ranks have exploded in recent memory. "I hike all the time," she said. "Barry and I have hiked in South America, in the Caribbean, the Mediterranean, in Africa."

So no mammoth Timberlands with lug soles for her, no Mad Rock rubberized climbing shoes. "I love Tevas, but if you step on rocks...." She shrugged, suggesting the worst. "It's all about feeling secure."

Her favorite is a pair from Lowa, the German hiking boot company ? the Klondike Mid GTX LS II, to be exact. At $150, they are one of Lowa's best sellers. As Gun Week magazine put it, "They are all-day-long comfortable."

Kitted out with a waterproof Gore-Tex liner, the boots are light ? just 1.1 pounds each ? yet sturdy enough to reinforce her foot and ankle. "It's all about the ankle," Ms. Von Furstenberg cautioned.

While hiking is in theory a total escape, she does take along work ? or rather, she takes her hikes back to work. Squirreling away leaves, sticks and shells in her pack, or taking photographs of them, is how she invents new fabric designs, she said.

And fashionista that she is, she sees a certain allure to a good hiking boot. "When you're hiking, you look glamorous if you look real," she said. "These are sexy in a weird way, because of the power they give you. You feel you can handle anything."

Fine for the country, but in the city, you don't want to get too secure. That's why stilettos are good: you have to stay on your toes.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Contact Us Back to Top

Christoph Nieman

June 5, 2005

Portrait of the Artist as a 17th-Century Oprah

By CAROL KINO

SINCE the advent of the museum blockbuster in the 1970's, which helped usher in the concept of the museum as a must destination, art's growing popularity with the mainstream public has become something of a double-edged sword.

For those who have always considered themselves art lovers, the reactions tend to fall into two camps. There are the Pollyannas, delighted to see more people getting clued in to the joys of art. And then there are the skeptics - those who deplore the idea of art being used to pump up tourism, or who simply resent all those extra bodies getting in the way.

And now the popularization of artists and museums has yielded something else to feel ambivalent about: the first art-focused self-help book, "How Rembrandt Reveals Your Beautiful, Imperfect Self: Life Lessons From the Master."

Previous works by the author, Roger Housden, who wrote the best-selling "Ten Poems to Change Your Life," have celebrated poets like Rumi and Robert Bly. This time he metes out the pop-Buddhist-mysticism treatment to the life and work of the 17th-century Dutch master.

Mr. Housden's book is largely focused on Rembrandt's renowned self-portraits, in which he charted the changes in his visage from cocky youthful promise to destitute old age. The gist is that despite Rembrandt's all-too-human flaws, he at least had the courage to repeatedly face himself in the mirror - and we can learn from this example. To this end, Mr. Housden has shoehorned the master's life and work into six "lessons," with titles like "Open Your Eyes," "Troubles Will Come" and "Keep the Faith." It almost goes without saying that we encounter "the presence of angels" along the way.

Although museum officials might be expected to dismiss this book as a frivolous exercise, that doesn't seem to be happening. Its publication has been timed to coincide with the show "Rembrandt's Late Religious Portraits," which originated at the National Gallery of Art in Washington. It reopens Tuesday at the J. Paul Getty Museum in Los Angeles, and on Friday Mr. Housden is scheduled to give two gallery talks and hold two book signings there. Effectively that gives his book the museum's imprimatur. The reason? "Synergy between his new book and our new exhibition," said Cathryn Carpenter, the Getty's programming director. "It just seemed to fit so well."

And although skeptics might be appalled by the book's sentimentality, some among us may similarly find it hard to dismiss out of hand, because Rembrandt, in Mr. Housden's retelling, seems a weirdly savvy choice for a contemporary everyman figure.

Not only did the artist, after his wife's death, juggle what Mr. Housden terms a "blended" family, as well as two live-in romantic relationships, one of which disintegrated into ugly legal actions; he also managed to bankrupt himself by the age of 50 with out-of-control spending and an ill-advised real estate loan.

Better yet, the story of his descent and redemption takes place in 17th-century Amsterdam, soon after that city had spawned the world's first stock market. Certainly, the art world in which Rembrandt rose to fame seems remarkably like our own: it was driven by wide and eager collecting and rampant speculation, and offered so many artists and opportunities that no clearly dominant style emerged.

Indeed, Mr. Housden is not the first writer to seek inspiration in 17th-century Dutch art and life. In the last six years, many others have mined this golden age: think of "Girl in Hyacinth Blue" by Susan Vreeland, "Girl With a Pearl Earring" by Tracy Chevalier and "Tulip Fever" by Deborah Moggach. Each uses a portrait to dramatize the way individual lives can be mirrored and transformed when a person's image is transmuted into paint.

And for anyone who has ever sat through a high-stakes auction, where artworks often get applauded for the amount of money they bring, there seems nothing too terrible about encouraging more people to see creativity, struggle and personal inspiration, rather than dollar signs, when they look at paintings on museum walls.

Mr. Housden certainly does his bit by presenting Rembrandt as a tortured soul who was impelled to paint and act as the spirit moved him, whatever the consequences. Yet many will undoubtedly recoil at this portrayal, for if there is anything that makes Rembrandt seem truly contemporary, it is that, especially since his death, his life and body of work have always been marked by one constant: continual flux and reassessment. (This is also what makes him such a perfect pop-Buddhist subject.)

Though Rembrandt was greatly admired in his lifetime and beyond, he was initially viewed as something of an iconoclast because of his idiosyncratic choice of subject matter and style. Yet in the 19th century - another era when art was wildly popular, with a widespread audience to match - he was recast as a free-spirited Romantic genius, intent on pursuing his own bliss. (This is pretty much how Mr. Housden presents him today.) No wonder that from this point the number of paintings attributed to Rembrandt steadily increased, leaping from 377 in 1900 to 714 in 1923.

In 1968, the Dutch government began financing the Rembrandt Research Project, an association of scholars who set about sorting the real Rembrandts from the chaff. Since then, many works that earlier generations believed to be by the master himself - including at least one self-portrait - have been reidentified as the work of his multitudinous students and workshop assistants.

One result has been that in the last 20 years - what some might call the golden age of American skepticism - much ink has been spilled on Rembrandt reattributions and reassessments. Gary Schwartz, in his 1985 biography, "Rembrandt: His Life, His Paintings," asserted that the artist's aesthetic choices were often influenced by his patrons' tastes. Svetlana Alpers, in "Rembrandt's Enterprise: The Studio and the Market" (1988), illuminated his marketing strategies. And many shows organized since then have focused on what Rembrandt is or isn't, most notably the Metropolitan Museum's 1995 "Rembrandt/Not Rembrandt."

Mr. Housden's book includes a reading list, as well as an appendix noting all the places in this country where it is possible to see Rembrandt's paintings, including the Wynn Collection in Las Vegas. Yet it includes no nod to Ms. Alpers or Mr. Schwartz, and no mention of the Rembrandt Research Project.

As Simon Schama, author of the 1999 biography "Rembrandt's Eyes," once wrote in this newspaper, "Every generation gets the Rembrandt it deserves." If there is one lesson we can glean from Rembrandt's life and work today, it is probably that fervently held romantic beliefs are seldom based in reality. The publication of Mr. Housden's book underlines that in art, as in life, we tend to cling to them anyway.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Contact Us Back to Top

Philip Anderson

June 5, 2005

Lessons in Gratitude, at the Basement Sink

By BEN STEIN

MY father entered Williams College in Williamstown, Mass., in September 1931. The United States was entering the downswing of a small uptick at the beginning of what would be the worst industrial depression in history.

My father had an unemployed father (a former skilled tool-and-die maker) and a mother who worked as a sales clerk at a department store in Schenectady, N.Y. He had no money, no financial reserves, no social connections.

He told me of many jobs while he was at Williams, but one stays in my memory a dozen times a day, especially when I am working by traveling through a dismal, endless security line or waiting in a line to check into a hotel or noticing that my bed in my new hotel has a ripped sheet and is next to a noisy air-conditioner.

My father had a job thanks to a kindly man named Taylor Ostrander at a fraternity called Sigma Psi. My father's job was to wash dishes in the basement of the frat house as the other boys finished their lunches and dinners. (One of the boys, Richard Helms, went on to be director of the C.I.A., but that's another story.) He toiled down there at a huge sink, with steam rising and detergent getting on his unimaginably soft hands. He wore a stocking cap to keep his already curly hair from going crazy.

It was the 1930's, and Jews weren't allowed in any fraternity at Williams. Many years later, maybe in the 1980's, by which time my father had become a major economist and public policy discussant, I asked him if he felt angry about having to wash dishes to pay his way through school in a fraternity that didn't admit Jews. "Not at all," he said. "I didn't have the luxury of feeling aggrieved. I was just grateful to have a job so I could go to one of the best schools in the country."

I think that this was the secret ingredient - aside from astonishing intelligence and versatility - in my father's success and happiness. He did not feel that he had the luxury of feeling aggrieved. He was just grateful to have a chance. Or, I can say, he was grateful for the opportunities he had been given. I think about this in other situations, too. A few days ago, on a United Airlines flight from San Francisco to Denver, a group of flight attendants gathered near my seat in the last row of first class. One was either wearing or displaying a perfume I was allergic to, and I went into a wild asthmatic attack in which I could simply not breathe for an uncomfortable amount of time.

When I revived, I thought of lodging a complaint and throwing a fit. But then I thought: "Well, these poor people. Think of what United employees are going through. I am just grateful I have a job. Why torture them any more than they are already tortured?"

I was on my way to another job. I got to the next stop in my journey, Baltimore, and my driver could not recall where he had left the car. We had to have the airport police find it for us. He also did not know his way from Baltimore to Washington. (I am not kidding.) Exhausted as I was, I had to guide him all of the way. Never mind. I was grateful that I was in a car with a driver and on my way to a superimportant gig. This man was probably about where my father was in 1931. I decided not to pick on him.

Now, I have found that I cannot predict the stock market except over very long periods. I cannot tell you when the housing bubble will burst - only that it will burst. I cannot tell you when the dollar will stop rallying - only that it will stop. So I cannot tell you anything that, in a few minutes, will tell you how to be rich.

But I can tell you how to feel rich, which is far better, let me tell you firsthand, than being rich. Be grateful. Be grateful you have a job, even if it takes you to the world's worst airport, Dulles, and to the world's worst security lines, also at Dulles.

Be grateful you have a job to travel to, even if you must travel to a hotel room where the previous tenant was a cigar tester for Fidel Castro. (But do ask for another room.) Be grateful about everything and you'll feel a lot richer than the billionaires I know who are always moaning about everything that happens and who lament, like King Canute, that they cannot control the waves of the market or the business cycle.

When I got to Washington with my novitiate driver, I rested. The next day, I spoke to about 250 kids, perhaps ages 5 to 15, about how grateful the nation was to them. Their fathers had died in the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and in training accidents. They were as good, brave, intelligent and yet haunted-looking as any kids I have ever met. Be grateful for their sacrifice and that your son or daughter is not one of them.

Then I spoke to about 500 widows, widowers, mothers, fathers, fianc?es of men who had been killed in the war on terror. They were totally devoted to one another and to helping one another through their grueling losses. They were probably the most spiritually fit, unselfish human beings I have ever met. One showed me the contents of his son's wallet when his son was killed. A dollar bill still had a blood stain on it. The father cried when he showed it to me. Be grateful that the armed forces of this country have such brave families.

AS I told them, we could do without Hollywood for a century. We could not do without them and their sacrifice for a week. Gratitude. As my pal Phil DeMuth says, it's the only totally reliable get-rich-quick scheme. Gratitude. Losing the luxury of feeling aggrieved when, if you look closely, you have an opportunity. My father washed dishes at the Sigma Psi house so that he could build an education and a life for the family he did not even have yet.

At my house, I always insist on doing the dishes, and I feel a thrill of gratitude for what washing a dish can do with every swipe of the sponge. Wiping away the selfishness of the moment, building a life for my son. The zen of dishwashing. The zen of gratitude. The zen of riches. Thanks, Pop.

Ben Stein is a lawyer, writer, actor and economist. E-mail: ebiz@nytimes.com.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Contact Us Back to Top

Sara D. Davis for The New York Times

WORKING - Dr. Mike Morris of Duke University Medical Center, photographs a wound before surgery.

June 8, 2005

USES

From Broken Bones to Decayed Buildings

By SANDEEP JUNNARKAR

TO his tools of the trade - surgical navigation equipment, intramedullary nails and plate and screw sets - Dr. Steven A. Olson, an orthopedic trauma surgeon at Duke University Medical Center, has added a simple two-megapixel camera.

When a patient is brought into the emergency room with, say, severe skeletal trauma, caused by a car accident or a shooting, one of the first steps for Dr. Olson's medical interns is to photograph the crushed bones and shredded tendons. The medical team then realigns the bones and applies a sterile dressing as a prelude to surgery.

In years past, Dr. Olson said, surgeons would have removed the dressing each time they wanted to study the damage to plan the surgery. Now, the resolution of the images taken with the camera is enough to provide fine detail of the injury from various angles.

"We can leave the wound covered in the meantime, so there is no continual contamination from exposure to the outside environment," Dr. Olson said. "By using the images, we can make a treatment plan for this patient."

Digital cameras - praised as one of the most rapidly adopted consumer gadgets - are finding usefulness in a variety of professions that traditionally have little or nothing to do with photography.

"In the consumer realm, our in-boxes are being flooded with baby pictures," said John Maeda, a professor of media and science at the Media Lab at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. "But in the professional realm, it is transforming professional fields because it is so easy to discuss something not simply based on text - which is what we were limited to before."

A Teacher's Pet

Rebecca Rupert, a language arts and communications teacher at Aurora Alternative High School in Bloomington, Ind., brought digital photography into her classroom with a big splash. Last month, the students in her civil rights literature class went beyond their assigned readings by traveling to Montgomery, Selma and Birmingham in Alabama and to Memphis to photograph their impressions of a region inextricably linked to the civil rights movement. Back in class, the students transformed their snapshots into photo essays, supplemented by text.

"Having visual literacy is really important and I try to bring that into my classes as much as possible," Ms. Rupert said. "I want kids to be able to use visual medium to express themselves and to communicate in words what they are seeing - it is another kind of knowing."

More schools have incorporated digital cameras across their curriculums. In higher grades, students use them to document science experiments, while younger children illustrate alphabet books by taking pictures of objects familiar to them. Teachers often prepare instruction booklets for their students with easy-to-follow steps illustrated with photographs.

Some teachers fret that if digital cameras are not part of a classroom, the digital divide will widen. But they note that digital cameras are one of the most affordable technologies. "Most school budgets can provide some digital cameras for every school, as opposed to more expensive, sophisticated technology," said Sandy Beck, an instructional technology specialist at Forsyth County Schools in Georgia.

Imagining Home

At 745 Fox Street in the Bronx sits a dilapidated but landmark-designated building dated 1850. Developers have proposed constructing a low-income housing complex to rise behind the old building. But they must first show the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission that the new structure will not obscure the landmark building.

Tony Shitemi, an architect with Urban Architectural Initiatives in Manhattan, which designed the housing complex, enlisted the help of a digital camera to show how the building's historical value would be preserved. Using image editing software, Mr. Shitemi spliced the rendering of the new building onto the picture of the old building - which was also digitally restored.

Other fields that create living and working spaces, like construction and interior design, are also integrating the use of digital cameras. Interior designers can photograph sofas at furniture stores, for example, then hold up the liquid crystal display within a room they are arranging to visualize how well the design works.

HNTB, an engineering, architecture and construction management company in Kansas City, Mo., oversees projects that can extend over a decade. When building highways, HNTB feeds panoramic digital photographs into a database to allow clients to see how the work is progressing without visiting the site.

The Picture of Health

Skin conditions are often the first sign of H.I.V. infection. But in sub-Saharan Africa - where AIDS is a full-blown epidemic - dermatologists are a rarity. To bridge the gap, Dr. Roy M. Colven, the head of dermatology at the Harborview Medical Center in Seattle, studies the digital images and written descriptions e-mailed to him by primary-care doctors in South African provincial hospitals. He received a Fulbright Award last year to set up a long-distance consulting program based in Cape Town, where he is working for another month.

This way, from his office at the University of Cape Town, Dr. Colven "sees" about 12 patients a month, a number that is steadily growing.

Dr. Colven, who uses a four-megapixel camera, said the resolution was good enough for effective diagnosis of skin diseases. "It is relatively low resolution," he said, "but this spares file size on a relatively low bandwidth e-mail system."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top