Wednesday, March 16, 2005

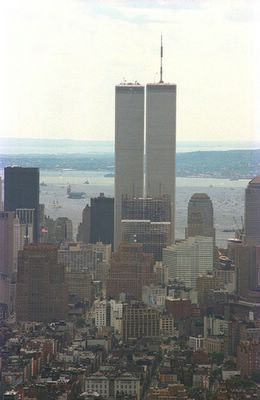

This photo was taken from the observation deck of the Empire State Building. I used my 200mm lens with the 2x teleconverter. You can see in the harbor to the left of the south tower the aircraft carrier USS John F. Kennedy. It was there as part of the regatta celebrating the 100th anniversary of the Statue of Liberty.

Photographs © 1986/1998, web page © 2004, R. S. Wilson.

U.S. Report Lists Possibilities for Terrorist Attacks and Likely Toll By ERIC LIPTON

ASHINGTON, March 15 - The Department of Homeland Security, trying to focus antiterrorism spending better nationwide, has identified a dozen possible strikes it views as most plausible or devastating, including detonation of a nuclear device in a major city, release of sarin nerve agent in office buildings and a truck bombing of a sports arena. The document, known simply as the National Planning Scenarios, reads more like a doomsday plan, offering estimates of the probable deaths and economic damage caused by each type of attack. They include blowing up a chlorine tank, killing 17,500 people and injuring more than 100,000; spreading pneumonic plague in the bathrooms of an airport, sports arena and train station, killing 2,500 and sickening 8,000 worldwide; and infecting cattle with foot-and-mouth disease at several sites, costing hundreds of millions of dollars in losses. Specific locations are not named because the events could unfold in many major metropolitan or rural areas, the document says. The agency's objective is not to scare the public, officials said, and they have no credible intelligence that such attacks are planned. The department did not intend to release the document publicly, but a draft of it was inadvertently posted on a Hawaii state government Web site. By identifying possible attacks and specifying what government agencies should do to prevent, respond to and recover from them, Homeland Security is trying for the first time to define what "prepared" means, officials said. That will help decide how billions of federal dollars are distributed in the future. Cities like New York that have targets with economic and symbolic value, or places with hazardous facilities like chemical plants could get a bigger share of agency money than before, while less vulnerable communities could receive less. "We live in a world of finite resources, whether they be personnel or funding," said Matt A. Mayer, acting executive director of the Office of State and Local Government Coordination and Preparedness at the Homeland Security Department, which is in charge of the effort. President Bush requested the list of priorities 15 months ago to address a widespread criticism of Homeland Security from members of Congress and antiterrorism experts that it was wasting money by spreading it out instead of focusing on areas or targets at greatest risk. Critics also have faulted the agency for not having a detailed plan on how to eliminate or reduce vulnerabilities. Michael Chertoff, the new secretary of homeland security, has made it clear that this risk-based planning will be a central theme of his tenure, saying that the nation must do a better job of identifying the greatest threats and then move aggressively to deal with them. "There's risk everywhere; risk is a part of life," Mr. Chertoff said in testimony before the Senate last week. "I think one thing I've tried to be clear in saying is we will not eliminate every risk." The goal of the document's planners was not to identify every type of possible terrorist attack. It does not include an airplane hijacking, for example, because "there are well developed and tested response plans" for such an incident. Planners included the threats they considered the most plausible or devastating, and that represented a range of the calamities that communities might need to prepare for, said Marc Short, a department spokesman. "Each scenario generally reflects suspected terrorist capabilities and known tradecraft," the document says. To ensure that emergency planning is adequate for most possible hazards, three catastrophic natural events are included: an influenza pandemic, a magnitude 7.2 earthquake in a major city and a slow-moving Category 5 hurricane hitting a major East Coast city. The strike possibilities were used to create a comprehensive list of the capabilities and actions necessary to prevent attacks or handle incidents once they happen, like searching for the injured, treating the surge of victims at hospitals, distributing mass quantities of medicine and collecting the dead. Once the White House approves the plan, which could happen within the next month, state and local governments will be asked to identify gaps in fulfilling the demands placed upon them by the possible strikes, officials said. No terrorist groups are identified in the documents. Instead, those responsible for the various hypothetical attacks are called Universal Adversary. The most devastating of the possible attacks - as measured by loss of life and economic impact - would be a nuclear bomb, the explosion of a liquid chlorine tank and an aerosol anthrax attack. The anthrax attack involves terrorists filling a truck with an aerosolized version of anthrax and driving through five cities over two weeks spraying it into the air. Public health officials, the report predicts, would probably not know of the initial attack until a day or two after it started. By the time it was over, an estimated 350,000 people would be exposed, and about 13,200 would die, the report predicts. The emphasis on casualty predictions is a critical part of the process, because Homeland Security officials want to establish what kinds of demands these incidents would place upon the public health and emergency response system. "The public will want to know very quickly if it is safe to remain in the affected city and surrounding regions," the anthrax attack summary says. "Many persons will flee regardless of the public health guidance that is provided." Even in some cases where the expected casualties are relatively small, the document lays out extraordinary economic consequences, as with a radiological dispersal device, known as a "dirty bomb." The planning document predicts 540 initial deaths, but within 20 minutes, a radioactive plume would spread across 36 blocks, contaminating businesses, schools, shopping areas and homes, as well as transit systems and a sewage treatment plant. The authors of the reports have tried to make each possible attack as realistic as possible, providing details on how terrorists would obtain deadly chemicals, for example, and what equipment they would be likely to use to distribute it. But the document makes clear that "the Federal Bureau of Investigation is unaware of any credible intelligence that indicates that such an attack is being planned." Even so, local and state governments nationwide will soon be required to collaboratively plan their responses to these possible catastrophes. Starting perhaps as early as 2006, most communities would be expected to share specially trained personnel to handle certain hazardous materials, for example, instead of each city or town having its own unit. To prioritize spending nationwide, communities or regions will be ranked by population, population density and an inventory of critical infrastructure in the region. The communities in the first tier, the largest jurisdictions with the highest-value targets, will be expected to prepare more comprehensively than other communities, so they would be eligible for more federal money. "We can't spend equal amounts of money everywhere," said Mr. Mayer, of the Homeland Security Department. To some, the extraordinarily detailed planning documents in this effort - like a list of more than 1,500 distinct tasks that might need to be performed in these calamities - are an example of a Washington bureaucracy gone wild. "The goal has to be to get things down to a manageable checklist," said Gary C. Scott, chief of the Campbell County Fire Department in Gillette, Wyo., who has served on one of the many advisory committees helping create the reports. "This is not a document you can decipher when you are on a scene. It scared the living daylights out of people." But federal officials and some domestic security experts say they are convinced that this is a threshold event in the national process of responding to the 2001 attacks. "Our country is at risk of spending ourselves to death without knowing the end site of what it takes to be prepared," said David Heyman, director of the homeland security program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, a Washington-based research organization. "We have a great sense of vulnerability, but no sense of what it takes to be prepared. These scenarios provide us with an opportunity to address that." Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company

Former WorldCom Inc. Chief Executive Bernard Ebbers (R) puts his arm around his tearful wife, Kristy (L), as they leave court after Ebbers was found guilty by a federal jury of fraud charges related to the $11 billion accounting scandal at the telecommunications company, March 15, 2005 in New York. Ebbers, 63, was also found guilty of conspiracy and filing false documents with regulators. He faces up to 85 years in prison when he is sentenced. REUTERS/Henny Ray Abrams

NEWS ANALYSIS

Ebbers, on Witness Stand, May Have Lost His Case

By JONATHAN D. GLATER and KEN BELSON

On trial for perpetrating one of the biggest corporate frauds ever, Bernard J. Ebbers, the former chief executive of WorldCom, helped to convict himself.

"It hurt him," said one juror, who asked not to be identified.

The devastating impact of Mr. Ebbers's testimony on the witness stand highlights the Catch-22 facing defendants and their lawyers in criminal cases: testify and risk a bad performance during cross-examination, or refuse to testify and risk having jurors rely on the prosecutors' characterizations. For Mr. Ebbers, having seen his legacy shattered and facing the prospect of spending the rest of his life in prison, there was little choice.

The government's principal accusations against him were based on the testimony of Scott D. Sullivan, WorldCom's former chief financial officer, who pleaded guilty to fraud charges. Mr. Sullivan offered the only direct evidence that Mr. Ebbers had known about the fraud. To leave unanswered his version of events was too dangerous, Mr. Ebbers's lawyer has said.

But Mr. Ebbers's evasiveness and defensive posture on cross-examination left a lasting impression on jurors hearing his case in federal court in Manhattan.

The jury clearly concluded that the testimony of Mr. Sullivan was more credible than that of Mr. Ebbers, even though the jurors did not fully believe Mr. Sullivan either, according to Peter Nulty, the father of Sarah Nulty, juror No. 10. Mr. Nulty posted his daughter's views of the jury's deliberations at estrong.com, a financial newsletter's Web site, last night, writing that "no one on the jury trusted the testimony of the prosecution's star witness."

The verdict was a victory for prosecutors, for whom a verdict of not guilty would have been a black eye. It was a crushing defeat for Mr. Ebbers's lawyers, who built a solid case but ultimately failed to win the credibility battle. "Nobody looked at this case as a lay-down case for the government," said Sean O'Shea, a criminal defense lawyer in New York. "It was a high-risk play."

Members of the jury took their responsibilities seriously, the juror who asked not to be named said in a telephone interview last night. That was why deliberations took eight days and jurors asked to review dozens of documents. "It was just for reviewing. It took so long," the juror said. "A lot of testimony we heard weeks, even months ago."

And jurors did not want to make a mistake, he said. "Everybody just wanted to be sure, really, that's all."

The jury did not go through the charges in order but took first what they considered easier allegations, involving filing of false documents with the Securities and Exchange Commission. They then moved to the more difficult charge of conspiracy.

"We went pretty much to the securities on down, and then went to the conspiracy," the juror said. "That was the count we wanted to look at in depth."

In the pre- Enron era, the case against Mr. Ebbers might have been settled, several lawyers said. But the thirst for retribution from investors, employees and others burned by the enormous fraud at WorldCom and other companies is too strong.

The unwillingness of the government to offer a decent plea-bargaining agreement left Mr. Ebbers with little choice but to go to trial. And once on trial, it became essential for Mr. Ebbers to respond directly to Mr. Sullivan's testimony that he was directed by Mr. Ebbers to make the fraudulent accounting changes.

Yet some lawyers, like Mr. O'Shea, said that the Ebbers case was winnable for the defense. "Sometimes defense lawyers get called upon to try cases where it's just very, very difficult," Mr. O'Shea said. "One, the evidence is very difficult. Two, the environment is very difficult."

Reid H. Weingarten, Mr. Ebbers's lawyer, also had significant obstacles to overcome. For one thing, some central facts about the fraud were not at issue.

"Ebbers's counsel couldn't dispute there was fraud since Sullivan had pled guilty to it," said Jason Brown, a former federal prosecutor who now practices at Holland & Knight in New York. "Typically you want to defend a case by arguing that these are complicated issues that don't rise to the level of a fraud."

But according to Mr. Nulty's Web site posting, the jury "concluded that with his personal fortune evaporating and the company he built sinking, it was inconceivable that Ebbers was not paying attention" to the details of WorldCom's finances.

The conviction does not have a direct effect on other cases against high-profile executives, but in subtle and indirect ways, it may, said Melinda Haag, former chief of the white-collar section of the United States attorney's office in San Francisco and now a partner at Orrick Herrington & Sutcliffe.

"You have to hope and believe that the cases are fact-specific, and that the fact there was a conviction in this case means nothing," Ms. Haag said. "But the concern in the defense bar is, jurors are affected when they see this kind of thing." The trial of Mr. Ebbers took its toll on members of the jury, too, said a third juror reached by telephone last night. Wearily, she said, "I want my life back, is all."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy

Former WorldCom Chief Executive Bernard Ebbers arrives at federal court March 15, 2005 in New York. Ebbers was found guilty by a federal jury on Tuesday of fraud charges related to the $11 billion accounting scandal at the telecommunications company. Ebbers, 63, was also found guilty of conspiracy and filing false documents with regulators. He faces up to 85 years in prison when he is sentenced. (Henny Ray Abrams/Reuters)

Ex-Chief of WorldCom Convicted of Fraud Charges

By KEN BELSON

Bernard J. Ebbers, the former chief executive of WorldCom, was found guilty today on all counts in orchestrating a record $11 billion fraud that came to symbolize the telecommunications bubble of the 1990's and excesses that were uncovered in its aftermath.

The seven women and five men on the federal court jury delivered their decision after deliberating for about 40 hours over eight days. Mr. Ebbers was convicted of securities fraud, conspiracy and seven counts of filing false reports with regulators. He now faces what effectively could amount to a life sentence. Sentencing was set for June 13, and his bail was continued.

The case has been one of the most widely watched corporate fraud cases in recent years. Mr. Ebbers and WorldCom have been at the center of a swirl of scandals that have cast doubt on corporate accounting methods, the role of Wall Street financial analysts and investment bankers who misrepresented stocks and bonds. Mr. Ebbers is the most prominent executive yet convicted of wrongdoing in a corporate fraud case. His conviction may presage verdicts in cases against others executives, who, like Mr. Ebbers, claim that they were unaware of the fraud committed on their watch.

The verdict is a somber culmination of Mr. Ebbers's outsized rags-to-riches-to-rags story. From a modest background and with little schooling in technology or accounting, he turned a tiny reseller of long-distance phone services in Mississippi into an global telecommunications titan. Once worth more than $1 billion, Mr. Ebbers was hailed for his vision and savvy during good times and accused of greed and deceit during bad times.

Despite a deluge of documents and hours of testimony about intricate accounting procedures, the case essentially came down to Mr. Ebbers's word against that of Scott D. Sullivan, WorldCom's former chief financial officer, who said he had been directed by Mr. Ebbers to doctor WorldCom's accounts.

In the Manhattan courtroom today, Mr. Ebbers sat motionless as the jury forewoman, Theodora Evans, read the decision. His hands clasped in front of him, Mr. Ebbers's face was ashen by the time the drumbeat of nine guilty verdicts was read. His wife, Kristie, seated in the first row behind him, started weeping after the second verdict was read. When count five was read, her daughter, Carley, huddled closer.

After the jurors, judge and prosecutors left the courtroom, several dozen reporters waited in near-silence as Mr. Ebbers and his lawyers put on their coats to leave. Mr. Ebbers sipped on a water bottle and hugged his wife, who patted him on the back in return.

Mr. Ebbers left the courthouse holding his wife's hand and his daughter's arm. The three were chased by a gaggle of reporters and television cameramen before they hailed a yellow cab in a quick getaway. They made no public comments.

Mr. Ebbers's lawyer, Reid H. Weingarten, said he would appeal the verdict, saying the jury should have heard from three ex-WorldCom executives with intimate knowledge of the company's accounts and Mr. Ebbers's role in managing them. The executives refused to testify without immunity; the defense unsuccessfully filed three motions to gain their protection from prosecution.

"It would have been a profoundly different trial" if the executives had been granted immunity and testified, said Mr. Weingarten, who looked stunned shortly after the verdict. "From our vantage point, there's not one chance in the world that Bernie Ebbers cooked the books at WorldCom."

The outcome of the eight-week trial represents another victory for the government, which has stepped up its efforts in recent years to prosecute executives accused of securities fraud and other corporate crimes.

"Today's verdict is a triumph of our legal system and the application of our nation's laws against those who breach them," Attorney General Alberto R. Gonzales said in a statement. "We are satisfied the jury saw what we did in this case: that fraud at WorldCom extended from the middle-management levels of this company all the way to its top executive."

The pursuit of Mr. Ebbers, who was indicted a year ago after five of his former subordinates pleaded guilty to their role in the record fraud, is representative of the more aggressive approach that lawyers at the Department of Justice and Securities and Exchange Commission have been taking.

"Since the beginning of the Enron affair in 2002, the government has been in full advance," said Robert Giuffra, Jr., a lawyer in Sullivan & Cromwell's Criminal Defense and Investigations Group. "The victories for the defense have been few and far between, and with each one of these cases, you have to wonder when the defense will win."

The Ebbers verdict may also affect civil suits brought by shareholders against WorldCom's former bankers and directors. In a trial that is to start on Thursday, JPMorgan and several other banks that helped underwrite WorldCom's debt will defend themselves in a suit brought by the New York State Common Retirement Fund.

If a jury was willing to conclude that Mr. Ebbers knew about the fraud, some legal experts believe, a jury might find that the bankers should have known as well.

"The fact that Bernie Ebbers was found guilty does give the underwriter the possibility of saying we were defrauded too, but I don't think a jury is going to buy that," said Alan Bromberg, professor of law at Southern Methodist University in Dallas. "The underwriters with all their due diligence capability should have realized that there was fraud and either disclosed it or taken action to prevent it."

Many other banks, including Citigroup, have already agreed to pay $4 billion in penalties.

The conviction of Mr. Ebbers, who was defended by one of the most highly regarded white-collar criminal lawyers in the nation, may lead other executives accused of similar charges to strike deals with the government rather than take their chances in front of a jury. Widespread news coverage of corporate fraud cases and a spate of recent convictions have probably influenced juries toward the prosecution, many legal experts say, making it harder for defense lawyers to plead their clients' cases in the courtroom.

The verdict also amounts to another feather in the cap for David B. Anders, the assistant United States attorney who was the lead prosecutor in the case. Mr. Anders, 35, has now won a dozen convictions, including one against Frank Quattrone, the former investment banker who was found guilty of obstruction of justice last year.

During the Ebbers trial, Mr. Anders and his team built a methodical case that showed that the former WorldCom chief effectively ordered his chief financial officer, Mr. Sullivan, to illegally reclassify rising expenses and pump up revenue to meet the company's ambitious financial growth targets. Mr. Ebbers, the government contended, pushed Mr. Sullivan to doctor the company's books to mask WorldCom's deteriorating finances.

Mr. Ebbers, who borrowed hundreds of millions of dollars using his WorldCom stock as collateral, was desperate to reverse the long slide in the company's shares, the government argued.

Prosecutors called 14 witnesses, but none more important than Mr. Sullivan, who had already pled guilty to his role in the fraud and faces 25 years in jail himself. Mr. Sullivan was the only witness to say he spoke directly to Mr. Ebbers about the fraud, and who received instructions to proceed. Mr. Sullivan said he met with Mr. Ebbers alone, and no other witness corroborated his statements.

Mr. Weingarten contended that Mr. Ebbers was in the dark about the fraud, so much so that he continued to buy WorldCom stock even after he resigned as chief executive in April 2002, two months before internal auditors unearthed the fraud.

Mr. Weingarten also argued that Mr. Sullivan's testimony was suspect because he took the stand in hopes of receiving a reduced sentence.

The defense also called WorldCom's former chairman, Bert Roberts, who said Mr. Sullivan had told him that Mr. Ebbers did not know about fraudulent journal entries.

The climax of the trial, though, came on Feb. 28, when Mr. Weingarten took the risky step of putting Mr. Ebbers on the stand. There, Mr. Ebbers denied discussing any element of the fraud with Mr. Sullivan.

But during hours of cross-examination from Mr. Anders, Mr. Ebbers appeared far less sure of himself and at times seemed to evade even simple questions. In many cases, he provided long answers to questions that were not asked. He also did not recall many facts and encounters mentioned earlier in the trial. His inconsistent performance on the stand may have been one of the keys that persuaded the jury to rule against him.

Jurors, who mostly live in Manhattan and the Bronx and who included a train operator and a retired transit authority clerk, a worker for Time Warner Cable and several bank administrators, chose not to speak to reporters after their verdict was announced.

During their deliberations, the jurors called for dozens of documents and transcripts from the trial that did not seem to fit any recognizable pattern. Last Wednesday, they sent the judge, Barbara S. Jones, a note seeking instruction that included the phrase, "in order to find Mr. Ebbers guilty of counts three through nine...," suggesting they were leaning toward convicting Mr. Ebbers.

To the tens of thousands of Worldcom workers who lost their jobs, their savings and their dreams when the company failed in 2002, the Ebbers verdict is no doubt a satisfying one. The same probably goes for the many people who experienced Mr. Ebbers's brash style of business firsthand. One business associate recalled meeting with Mr. Ebbers when WorldCom was still flying high. When the meeting was over, the associate handed Mr. Ebbers his business card. Mr. Ebbers used it to pick his teeth.

Reporting for this article was contributed by Gretchen Morgenson, Colin Moynihan and Jonathan D. Glater.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy

Former WorldCom Chief Executive Bernard Ebbers(R) and his wife Kristy(L), leave court after Ebbers was found guilty by a federal jury of fraud charges related to the $11 billion accounting scandal at the telecommunications company, March 15, 2005 in New York. Ebbers, 63, was also found guilty of conspiracy and filing false documents with regulators. He faces up to 85 years in prison when he is sentenced. Photo by Henny Ray Abrams/Reuters