Friday, March 11, 2005

UPDATED 11:15 P.M. FRIDAY Governor offers reward in courthouse shooting spree > Fulton judge, court reporter and deputy killed; reward offered > By MIKE MORRIS

Atlanta police officer S.C. Shultz (right) and Atlanta Housing Authority Officer D.D. Jones (center) comfort a Fulton County deputy outside Grady Memorial Hospital

From left, Gov. Sonny Perdue, Fulton County Sheriff Myron Freeman and Dr. Jeffrey Salomone and lead the way to a press conference.

? Related story

Court reporter Julie Brandau, shown in a 2002 photo for a feature in the AJC Food section, was shot and killed.

? Related story

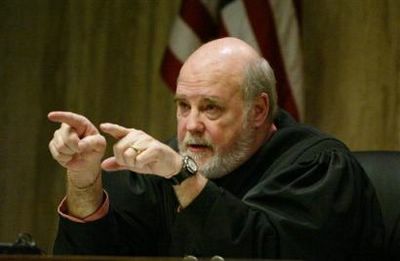

Fulton County Superior Court Judge Roland Barnes speaks during a hearing for Atlanta Thrashers' Dany Heatley in an Atlanta courtroom Feb. 6, 2005. Barnes and a court reporter were shot to death Friday, March 11, 2005 at the Fulton County Courthouse, authorities said. At least two others were wounded, and a search for the suspect was underway. (AP Photo/John Bazemore)

Fulton County Superior Court Judge Roland Barnes speaks during a hearing for Atlanta Thrashers' Dany Heatley in an Atlanta courtroom Feb. 6, 2005. Barnes and a court reporter were shot to death Friday, March 11, 2005 at the Fulton County Courthouse, authorities said. At least two others were wounded, and a search for the suspect was underway. (AP Photo/John Bazemore)

Fulton County Superior Court Judge Roland Barnes speaks in this recent file photo. (AP/John Bazemore)

International News

Fulton County Superior Court Judge Roland Barnes speaks in this recent file photo. (AP/John Bazemore)

Judge, court reporter, deputy shot to death, 1 other hurt at Atlanta courthouse

March 11, 2005 - 11:52

ATLANTA (AP) - A judge presiding over a rape trial was shot to death Friday along with two other people at the Fulton County Courthouse, authorities said. A fourth person was wounded and a search was underway for the suspect, the defendant in the trial.

Lt.-Gov. Mark Taylor confirmed that Superior Court Judge Rowland Barnes and his court reporter were killed. He gave no other details in announcing the deaths in the state Senate. A deputy died later at a hospital, while a second deputy had minor wounds, police said.

The judge was shot on the eighth floor of the courthouse, while one deputy was shot on a street corner just outside the building, said Officer Alan Osborne with the Atlanta Police Department.

Witnesses said the gunman carjacked a car and authorities were searching for a green Honda Accord that was hijacked from a newspaper reporter.

Fulton County Sheriff's Lieut. Clarence Huber identified the suspect as 33-year-old Brian Nichols, who was on trial on rape and other charges stemming from an incident in August. It was not immediately known how the suspect got a gun.

"We heard some noise. It sounded like three or four shots. At the time, we thought it was just an engine backfiring," said Chuck Cole, a civil defence attorney who was in an adjoining parking deck when he heard gunfire at around 9:10 a.m.

A sheriff's deputy died at Grady Hospital and a second was being treated for graze wounds, police Sgt. John Quigley said.

"I saw one person on the street that they were performing CPR on," said court reporter Amy McKee.

The Atlanta Journal-Constitution newsroom staff was told that Don O'Briant, a features reporter for the paper, was beaten by the suspect and carjacked outside the courthouse. Mike King, an editorial board member for the paper, said O'Briant was taken to Grady.

All the judges in the building were locked in their chambers. The courthouse and other buildings in downtown Atlanta were on lockdown. Traffic in the blocks surrounding the courthouse was backed up as police cruisers flooded the area looking for the suspect.

James Bailey, a juror at Nichols' trial, said the jury was not in the courtroom at the time of the shooting. Bailey said Nichols had made him and other jurors nervous. "Every time he looked up, he was staring at you," Bailey said. He said Barnes was the presiding judge.

Barnes was named to the Fulton County Superior Court bench in 1998.

Among cases handled by Barnes was the fatal 2003 car wreck by hockey star Dany Heatley that killed his 25-year-old teammate Dan Snyder. Heatley pleaded guilty and was sentenced Feb. 4 to three years on probation and ordered to give 150 speeches about the dangers of speeding.

Barnes, 64, also drew attention last month when he took the unusual step of ordering a mother of seven who pleaded guilty to killing her five-week-old daughter to undergo a medical procedure that would prevent her from having more children.

The shooting happened 11 days after the husband and elderly mother of a federal judge in Chicago were shot to death in her home. A man whose medical malpractice lawsuit was dismissed by the judge committed suicide and left a note saying he was the killer.

Friday, March 11, 2005

Fulton County (Ga.) Sheriff's Deputy Cynthia Hall is shown in an undated photo provided by the department. Hall was shot and killed Friday, March 11, 2005, in Atlanta, when a man being escorted into court for his rape trial stole a deputy's gun, killed the judge, Hall and another deputy, Sgt. Hoyt Teasley, then carjacked a reporter's vehicle to escape, setting off a massive manhunt and creating widespread chaos across the city. (AP Photo/Fulton County (Ga.) Sheriff)

Friday, March 11, 2005

Fulton County (Ga.) Sheriff's Sgt. Hoyt Teasley is shown in an undated photo provided by the department. Teasley was shot and killed Friday, March 11, 2005, in Atlanta, when a man being escorted into court for his rape trial stole a deputy's gun, killed the judge, Teasley and another deputy, Cynthia Hall, then carjacked a reporter's vehicle to escape, setting off a massive manhunt and creating widespread chaos across the city. (AP Photo/Fulton County (Ga.) Sheriff)

An F.B.I. agent closes the back doors to a vehicle as a group of agents loaded up at an Atlanta shopping center, Friday, March 11, 2005, to join the search for Brian Nichols, the suspect in the shooting of Superior Court Judge Rowland Barnes, his clerk and a Fulton County Deputy. Nichols was on trial for rape in the courthouse. (AP Photo/Ric Feld)

Blood Ties: 2 Officers' Long Path to Mob Murder IndictmentsBy ALAN FEUER and WILLIAM K. RASHBAUM

It looked at first like a classic gangland hit.

A Mercedes sat abandoned on a Brooklyn highway. A bullet-riddled corpse lay slumped across the seat. The dead man was Edward Lino, a Gambino family captain, who had helped kill Paul Castellano, the boss of bosses, and vault John Gotti into power. It was November 1990 and made men were dying. There was a dead mobster on the Belt Parkway. Business a usual, it seemed. It was the height of the Mafia's brutal civil war.

In the months and years that followed the shooting, the police, the Brooklyn district attorney and the federal prosecutor's office scoured the underworld for sources, tapping their informants for anything they had - a tip, a lead. One of them, a murderous Brooklyn turncoat, gave a scandalous report in 1994 that two corrupt detectives had, in fact, killed Mr. Lino, but the investigation, pursued for months, eventually stalled.

Eleven years of silence slowly followed.

This week, however, the silence was broken with a stunning indictment as investigators accused the two men of acts that their colleagues could have never fathomed 13 years ago when they first appeared at the scene of the blood-soaked car: that the men who held the guns that murdered Mr. Lino were not their rivals but their cousins, not cold-blooded Mafiosi but men, like them, in blue.

When Louis Eppolito and Stephen Caracappa were arrested Wednesday night at a dark-wood, white-clothed trattoria in Las Vegas, it brought to light some of the most shocking allegations of police corruption in New York City's history. The two were accused of being paid killers for the mob, charged with having taken part in at least eight murders - most while one or both were still on the New York force.

At their arraignment in Las Vegas, both men appeared yesterday in orange jump suits before their families in the courtroom to enter pleas of not guilty. A federal magistrate ordered them held without bail in Las Vegas pending their return to Brooklyn - where the story begins.

Louis Eppolito put on the patrolman's uniform in 1969. He had a fairly interesting background for a man who was sworn to uphold the law.

His father, Ralph, was a Gambino family soldier known in the underworld as Fat the Gangster. His uncle James was a Gambino captain who went by Jimmy the Clam.

Mr. Eppolito, however, loved his badge.

On the force, he wrote, a man could be a man. "You could swear and you could brawl and it was all in the name of helping other people," he said in "Mafia Cop" - a book he wrote with a co-author, Bob Drury. "I liked that. It was honorable."

His first assignment was the 63rd Precinct in Marine Park, Brooklyn, a quiet post in a well-kept middle-class neighborhood. By 1973, however, he had been sent to the 71st Precinct, which encompassed Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, East New York and East Flatbush, where he was born.

It was a "scum hole," Mr. Eppolito wrote, filled with drugs and pimps, prostitutes and guns. As a body builder (who had once been named Mr. New York City), he moved through the streets, imagining himself as some avenging angel, sometimes twisting arms, sometimes banging skulls.

The newspapers followed his career: "A tough cop's persistence and skill with gun, muscle and handcuffs were credited yesterday..." The Daily News once wrote. "A lone detective chased three hardened criminals..." it wrote another time. On Nov. 30, 1973, Detective Eppolito was splashed across its cover. "EPPOLITO," the headline ran, "DOES IT AGAIN."

Still, he was haunted by his family and his past. One night while Detective Eppolito was out for dinner with his wife, a mobster named Todo Marino picked up the check, he wrote in his book. He kissed the old man on the cheek in thanks, but the F.B.I. was watching. Mr. Eppolito was hauled down to meet with federal agents and answer for the kiss, he wrote. He was hauled down again years later when he was seen attending Mr. Marino's wake.

Even in his first years on the force, he would sometimes have informal meetings with gangland figures in his squad car, he recounted in his book: "I figured who was it going to hurt to stop and commiserate with an old Mustache Pete about his lumbago?"

Mr. Caracappa joined the force the same year as Mr. Eppolito, 1969. It was a time of civil and political unrest when the city rushed to get patrolmen on the streets. Rookies were hurried from the academy. There were shortened training regimens and abbreviated background checks. A number of officers hired in 1969 were later arrested or dismissed from the force.

The pair met working at the Brooklyn Robbery Squad and Mr. Eppolito coyly wrote they sometimes "used their brand of gentle persuasion to glean information from stoolies on minor raps." Mr. Caracappa eventually moved on to the elite Major Case Squad where he helped form the Organized Crime Homicide Unit and where he suddenly had access to a flood of secret information on the mob.

His specific assignment: investigate the Luchese crime family.

A Family Near Upheaval

By 1985, court papers say, the two detectives, had abandoned the idea of policing the mob, and instead had developed what prosecutors have called "a business relationship" with organized crime - chiefly with Anthony (Gaspipe) Casso, the Luchese family underboss.

At that point, the Luchese family was on the verge of upheaval. The family's boss, Anthony (Ducks) Corallo (so named for his knack for ducking subpoenas and convictions), would soon wind up indicted and prosecuted in federal court in Brooklyn as part of what was known as the commission trial, a sort of Waterloo for the New York mob.

In the end, the trial - one of the first to focus on the upper echelons of the Mafia - led to the conviction of the entire leadership of the Luchese family on racketeering charges, along with the conviction of two other Mafia dons.

It also led to a power vacuum in the family, which Mr. Casso and his new boss, Vittorio Amuso, were happy to fill.

Brutal and paranoid about traitorous informants, Mr. Casso - who later became a government witness and admitted his role in 36 murders - ruled with an iron fist,

He promoted vicious mobsters like George (Georgie Neck) Zappola and George (Goggles) Conte to the rank of captain. He was the sort of man who would breezily pick up $1,000 dinner bills or spend double that on an evening's worth of wine. But he also had a vicious bent: He was known for shooting pigeons off the rooftops and once used a forklift to drop 500 pounds of cargo on a dockworker's foot after hearing the man boast about his reinforced boots.

Nonetheless, under his control, the Lucheses prospered. They ran labor unions in the building trades and at the airports. And in a partnership with the Columbo family, they ran what was known as the Bypass Gang - a crew of seasoned burglars who would bypass sophisticated alarm systems, sometimes tunneling into banks from nearby stores.

Then on Sept. 6, 1986, Mr. Casso was the target of an attempted hit - shot and wounded in his car as it sat parked in the Flatlands section of Brooklyn. He escaped into a nearby restaurant, the Golden Ox.

When the investigators showed up at the crime scene, they were rocked by what they found in Mr. Casso's car: a list of license plate numbers.

And not just any license plate numbers. The numbers belonged to the unmarked cars the police themselves used while on surveillance.

The two detectives, is seems, had already begun to provide Mr. Casso with police information, according to prosecutors.

But after the 1986 shooting of Mr. Casso, the two detectives were asked to step up their efforts. Mr. Casso, who has since been imprisoned, wanted the two detectives to work on retainer: "$4,000 per month by Casso for NYPD and governmental information" - the names of informants, the timing of arrests - according to court papers.

"Any additional 'work,' " the papers charge, "was extra."

The extra work, prosecutors assert, came to include murder. In 1986, prosecutors have charged, the two detectives kidnapped an enemy of Mr. Casso, and delivered him up for execution. And then in 1990, according to the federal indictment, they pulled that Mercedes over on the Belt Parkway in Brooklyn. It was Mr. Caracappa, prosecutors say, who pulled the trigger.

The hit, prosecutors said, netted the pair $65,000, but they paid for it later. The turncoat who first told prosecutors of their crimes in 1994 was Mr. Casso himself.

Suspicions About Murder

About 18 months ago, five veteran investigators - four of them current or retired police detectives - came together to once again focus on what were some of the most sobering accusations they had ever heard about fellow officers.

Each man had special skills: Douglas Le Vien had worked undercover, convincing mobsters that he was a corrupt officer; Robert Intartaglio and Thomas Dades had long investigated mob figures; Joseph J. Ponzi specialized in murders; and William Oldham was an expert in building racketeering cases.

But the group, according to several law enforcement officials, had at least one thing in common: disgust with police detectives committing crimes for the mob. And some of them had long harbored suspicions that two of their retired colleagues - Mr. Eppolito and Mr. Caracappa - really had committed some of the worst sorts of crimes: murder.

Mr. Intartaglio, for his part, had a particular passion about the case, according to a colleague. It grew out of frustration he experienced more than a decade earlier, when one of his investigations seemed to keep stalling.

Then a city police detective, he was investigating the Luchese family's Bypass Gang, and it seemed like the mob was often one step ahead of him. "An informant was killed, matters were getting compromised," recalled a colleague, and it was unclear why.

Mr. Dades, for his part, had his suspicions strengthened when he stumbled across evidence in an unrelated mob case that seemed to raise the likelihood that Mr. Eppolito and Mr. Caracappa were guilty.

So, armed with frustration, anger and determination, they set about reviewing old files, and interviewing witnesses.

Because the accusations against the men were not new - they had first came to light in 1994 when Mr. Casso himself became a government witness and detailed what he said were their crimes - the men had a wealth of material to review. There were police and F.B.I. reports, the evidence from the earlier homicides, and other records. They set up what they came to call their War Room, in Brooklyn, to store the records and compare progress.

And, most critically, they came to secure the cooperation of a witness, who, according to the government's detention memo, is expected eventually to testify against the detectives.

Offficials in the office of the Brooklyn district attorney, Charles J. Hynes, which along with federal prosecutors was instrumental in making the case, would not discuss the witness.

But with the witness and that mixed band of investigators, the authorities were able to do what their predecessors in 1994 had not: Convince a grand jury to indict the two men on racketeering, murder and other charges.

An Actor Playing Wiseguys

Las Vegas was the perfect place for a detective to retire. There were golf courses and casinos, pretty women and plenty of sun.

Mr. Caracappa and Mr. Eppolito went there in the early 1990's after leaving the force. The former kept his fingers in the old life, finding work as a private investigator. The latter traded on his heritage, beginning a new career as a bit actor playing wiseguys, and drug dealers in movies like "Goodfellas" and "State of Grace."

They settled across the street from each other on Silver Bear Way, a bland block in a gated community that, in 1996, still lay on the edges of the desert. Eventually, the city's construction boom caught up with them and Silver Bear Way, like the rest of Las Vegas, was surrounded by the sprawl.

Mr. Eppolito lived with his wife and 89-year-old mother-in-law in a nice house adorned with the trappings of his new life. In his office, one official said, there was a wall of photographs that showed him posing with the stars: Robert De Niro, Charles Durning, Ray (Boom Boom) Mancini, the former lightweight champion who produced "Turn of Faith," a film that Mr. Eppolito wrote.

His roles in Hollywood were mostly small and colorful and of the sort that one could easily miss bending down to set one's popcorn on the floor. He was mentioned in the credits as "assassin" or "raid cop No. 1" or "waterfront hood." Still, in his book, Mr. Eppolito recalls being asked by Mr. De Niro himself for authentic pointers on the mob.

When the authorities raided Mr. Eppolito's house, they found more than a hundred guns, including two AK-47 assault rifles and a gold Luger pistol in a pair of safes, a law enforcement official said. His son, Anthony Eppolito, was also arrested in the case and charged with selling methamphetamines, the law enforcement official said.

Mr. Eppolito and Mr. Caracappa were themselves arrested Wednesday night at Piero's Restaurant, where Jerry Lewis often celebrates his birthday. Freddie Glusman, Piero's owner, was once married to the actress Diahann Carroll for a couple of weeks.

Their sojourn out west, it seems, had come to an end, Las Vegas style.

Joe Schoenmann, in Las Vegas, contributed reporting for this article.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Back to Top

It looked at first like a classic gangland hit.

A Mercedes sat abandoned on a Brooklyn highway. A bullet-riddled corpse lay slumped across the seat. The dead man was Edward Lino, a Gambino family captain, who had helped kill Paul Castellano, the boss of bosses, and vault John Gotti into power. It was November 1990 and made men were dying. There was a dead mobster on the Belt Parkway. Business a usual, it seemed. It was the height of the Mafia's brutal civil war.

In the months and years that followed the shooting, the police, the Brooklyn district attorney and the federal prosecutor's office scoured the underworld for sources, tapping their informants for anything they had - a tip, a lead. One of them, a murderous Brooklyn turncoat, gave a scandalous report in 1994 that two corrupt detectives had, in fact, killed Mr. Lino, but the investigation, pursued for months, eventually stalled.

Eleven years of silence slowly followed.

This week, however, the silence was broken with a stunning indictment as investigators accused the two men of acts that their colleagues could have never fathomed 13 years ago when they first appeared at the scene of the blood-soaked car: that the men who held the guns that murdered Mr. Lino were not their rivals but their cousins, not cold-blooded Mafiosi but men, like them, in blue.

When Louis Eppolito and Stephen Caracappa were arrested Wednesday night at a dark-wood, white-clothed trattoria in Las Vegas, it brought to light some of the most shocking allegations of police corruption in New York City's history. The two were accused of being paid killers for the mob, charged with having taken part in at least eight murders - most while one or both were still on the New York force.

At their arraignment in Las Vegas, both men appeared yesterday in orange jump suits before their families in the courtroom to enter pleas of not guilty. A federal magistrate ordered them held without bail in Las Vegas pending their return to Brooklyn - where the story begins.

Louis Eppolito put on the patrolman's uniform in 1969. He had a fairly interesting background for a man who was sworn to uphold the law.

His father, Ralph, was a Gambino family soldier known in the underworld as Fat the Gangster. His uncle James was a Gambino captain who went by Jimmy the Clam.

Mr. Eppolito, however, loved his badge.

On the force, he wrote, a man could be a man. "You could swear and you could brawl and it was all in the name of helping other people," he said in "Mafia Cop" - a book he wrote with a co-author, Bob Drury. "I liked that. It was honorable."

His first assignment was the 63rd Precinct in Marine Park, Brooklyn, a quiet post in a well-kept middle-class neighborhood. By 1973, however, he had been sent to the 71st Precinct, which encompassed Bedford-Stuyvesant, Crown Heights, East New York and East Flatbush, where he was born.

It was a "scum hole," Mr. Eppolito wrote, filled with drugs and pimps, prostitutes and guns. As a body builder (who had once been named Mr. New York City), he moved through the streets, imagining himself as some avenging angel, sometimes twisting arms, sometimes banging skulls.

The newspapers followed his career: "A tough cop's persistence and skill with gun, muscle and handcuffs were credited yesterday..." The Daily News once wrote. "A lone detective chased three hardened criminals..." it wrote another time. On Nov. 30, 1973, Detective Eppolito was splashed across its cover. "EPPOLITO," the headline ran, "DOES IT AGAIN."

Still, he was haunted by his family and his past. One night while Detective Eppolito was out for dinner with his wife, a mobster named Todo Marino picked up the check, he wrote in his book. He kissed the old man on the cheek in thanks, but the F.B.I. was watching. Mr. Eppolito was hauled down to meet with federal agents and answer for the kiss, he wrote. He was hauled down again years later when he was seen attending Mr. Marino's wake.

Even in his first years on the force, he would sometimes have informal meetings with gangland figures in his squad car, he recounted in his book: "I figured who was it going to hurt to stop and commiserate with an old Mustache Pete about his lumbago?"

Mr. Caracappa joined the force the same year as Mr. Eppolito, 1969. It was a time of civil and political unrest when the city rushed to get patrolmen on the streets. Rookies were hurried from the academy. There were shortened training regimens and abbreviated background checks. A number of officers hired in 1969 were later arrested or dismissed from the force.

The pair met working at the Brooklyn Robbery Squad and Mr. Eppolito coyly wrote they sometimes "used their brand of gentle persuasion to glean information from stoolies on minor raps." Mr. Caracappa eventually moved on to the elite Major Case Squad where he helped form the Organized Crime Homicide Unit and where he suddenly had access to a flood of secret information on the mob.

His specific assignment: investigate the Luchese crime family.

A Family Near Upheaval

By 1985, court papers say, the two detectives, had abandoned the idea of policing the mob, and instead had developed what prosecutors have called "a business relationship" with organized crime - chiefly with Anthony (Gaspipe) Casso, the Luchese family underboss.

At that point, the Luchese family was on the verge of upheaval. The family's boss, Anthony (Ducks) Corallo (so named for his knack for ducking subpoenas and convictions), would soon wind up indicted and prosecuted in federal court in Brooklyn as part of what was known as the commission trial, a sort of Waterloo for the New York mob.

In the end, the trial - one of the first to focus on the upper echelons of the Mafia - led to the conviction of the entire leadership of the Luchese family on racketeering charges, along with the conviction of two other Mafia dons.

It also led to a power vacuum in the family, which Mr. Casso and his new boss, Vittorio Amuso, were happy to fill.

Brutal and paranoid about traitorous informants, Mr. Casso - who later became a government witness and admitted his role in 36 murders - ruled with an iron fist,

He promoted vicious mobsters like George (Georgie Neck) Zappola and George (Goggles) Conte to the rank of captain. He was the sort of man who would breezily pick up $1,000 dinner bills or spend double that on an evening's worth of wine. But he also had a vicious bent: He was known for shooting pigeons off the rooftops and once used a forklift to drop 500 pounds of cargo on a dockworker's foot after hearing the man boast about his reinforced boots.

Nonetheless, under his control, the Lucheses prospered. They ran labor unions in the building trades and at the airports. And in a partnership with the Columbo family, they ran what was known as the Bypass Gang - a crew of seasoned burglars who would bypass sophisticated alarm systems, sometimes tunneling into banks from nearby stores.

Then on Sept. 6, 1986, Mr. Casso was the target of an attempted hit - shot and wounded in his car as it sat parked in the Flatlands section of Brooklyn. He escaped into a nearby restaurant, the Golden Ox.

When the investigators showed up at the crime scene, they were rocked by what they found in Mr. Casso's car: a list of license plate numbers.

And not just any license plate numbers. The numbers belonged to the unmarked cars the police themselves used while on surveillance.

The two detectives, is seems, had already begun to provide Mr. Casso with police information, according to prosecutors.

But after the 1986 shooting of Mr. Casso, the two detectives were asked to step up their efforts. Mr. Casso, who has since been imprisoned, wanted the two detectives to work on retainer: "$4,000 per month by Casso for NYPD and governmental information" - the names of informants, the timing of arrests - according to court papers.

"Any additional 'work,' " the papers charge, "was extra."

The extra work, prosecutors assert, came to include murder. In 1986, prosecutors have charged, the two detectives kidnapped an enemy of Mr. Casso, and delivered him up for execution. And then in 1990, according to the federal indictment, they pulled that Mercedes over on the Belt Parkway in Brooklyn. It was Mr. Caracappa, prosecutors say, who pulled the trigger.

The hit, prosecutors said, netted the pair $65,000, but they paid for it later. The turncoat who first told prosecutors of their crimes in 1994 was Mr. Casso himself.

Suspicions About Murder

About 18 months ago, five veteran investigators - four of them current or retired police detectives - came together to once again focus on what were some of the most sobering accusations they had ever heard about fellow officers.

Each man had special skills: Douglas Le Vien had worked undercover, convincing mobsters that he was a corrupt officer; Robert Intartaglio and Thomas Dades had long investigated mob figures; Joseph J. Ponzi specialized in murders; and William Oldham was an expert in building racketeering cases.

But the group, according to several law enforcement officials, had at least one thing in common: disgust with police detectives committing crimes for the mob. And some of them had long harbored suspicions that two of their retired colleagues - Mr. Eppolito and Mr. Caracappa - really had committed some of the worst sorts of crimes: murder.

Mr. Intartaglio, for his part, had a particular passion about the case, according to a colleague. It grew out of frustration he experienced more than a decade earlier, when one of his investigations seemed to keep stalling.

Then a city police detective, he was investigating the Luchese family's Bypass Gang, and it seemed like the mob was often one step ahead of him. "An informant was killed, matters were getting compromised," recalled a colleague, and it was unclear why.

Mr. Dades, for his part, had his suspicions strengthened when he stumbled across evidence in an unrelated mob case that seemed to raise the likelihood that Mr. Eppolito and Mr. Caracappa were guilty.

So, armed with frustration, anger and determination, they set about reviewing old files, and interviewing witnesses.

Because the accusations against the men were not new - they had first came to light in 1994 when Mr. Casso himself became a government witness and detailed what he said were their crimes - the men had a wealth of material to review. There were police and F.B.I. reports, the evidence from the earlier homicides, and other records. They set up what they came to call their War Room, in Brooklyn, to store the records and compare progress.

And, most critically, they came to secure the cooperation of a witness, who, according to the government's detention memo, is expected eventually to testify against the detectives.

Offficials in the office of the Brooklyn district attorney, Charles J. Hynes, which along with federal prosecutors was instrumental in making the case, would not discuss the witness.

But with the witness and that mixed band of investigators, the authorities were able to do what their predecessors in 1994 had not: Convince a grand jury to indict the two men on racketeering, murder and other charges.

An Actor Playing Wiseguys

Las Vegas was the perfect place for a detective to retire. There were golf courses and casinos, pretty women and plenty of sun.

Mr. Caracappa and Mr. Eppolito went there in the early 1990's after leaving the force. The former kept his fingers in the old life, finding work as a private investigator. The latter traded on his heritage, beginning a new career as a bit actor playing wiseguys, and drug dealers in movies like "Goodfellas" and "State of Grace."

They settled across the street from each other on Silver Bear Way, a bland block in a gated community that, in 1996, still lay on the edges of the desert. Eventually, the city's construction boom caught up with them and Silver Bear Way, like the rest of Las Vegas, was surrounded by the sprawl.

Mr. Eppolito lived with his wife and 89-year-old mother-in-law in a nice house adorned with the trappings of his new life. In his office, one official said, there was a wall of photographs that showed him posing with the stars: Robert De Niro, Charles Durning, Ray (Boom Boom) Mancini, the former lightweight champion who produced "Turn of Faith," a film that Mr. Eppolito wrote.

His roles in Hollywood were mostly small and colorful and of the sort that one could easily miss bending down to set one's popcorn on the floor. He was mentioned in the credits as "assassin" or "raid cop No. 1" or "waterfront hood." Still, in his book, Mr. Eppolito recalls being asked by Mr. De Niro himself for authentic pointers on the mob.

When the authorities raided Mr. Eppolito's house, they found more than a hundred guns, including two AK-47 assault rifles and a gold Luger pistol in a pair of safes, a law enforcement official said. His son, Anthony Eppolito, was also arrested in the case and charged with selling methamphetamines, the law enforcement official said.

Mr. Eppolito and Mr. Caracappa were themselves arrested Wednesday night at Piero's Restaurant, where Jerry Lewis often celebrates his birthday. Freddie Glusman, Piero's owner, was once married to the actress Diahann Carroll for a couple of weeks.

Their sojourn out west, it seems, had come to an end, Las Vegas style.

Joe Schoenmann, in Las Vegas, contributed reporting for this article.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Back to Top

Can Campaigns Profit From Online Irreverence?

By Robert MacMillanwashingtonpost.com Staff WriterFriday, March 11, 2005; 8:57 AM

The Internet isn't referred to as the "online universe" for nothing. Like the universe, it embodies the quality of infinite expansion. And as both the universe and the Internet expand, they can produce works of colossal beauty and furious destruction with an alarming randomness.

So it goes with Internet politics. For nearly a decade now, the Internet has proved accommodating as well as frustrating to political imagemakers and idolmakers who puzzle over the question of how cyberspace can propel their candidates ahead of the competition and into office.

This question will rise again at the Politics Online Conference in Washington. The conference, in its 12th year, invites campaign professionals to thrash and hash over the best way to harness the Internet as the 21st-century candidate's ace of spades.

The roll of speakers and panelists usually consists of political professionals, online-journalism bigwigs and political bloggers. This year's gathering, which started Thursday afternoon and runs through today at The George Washington University in Washington, will see an unusual guest at this morning's session -- Gregg Spiridellis, who with brother Evan co-founded JibJab Inc. and co-composed (and co-performed) the animated music video "This Land Is Your Land."

Featuring cavorting caricatures of Sen. John F. Kerry and President Bush singing a demented version of the eponymous song, the cartoon ricocheted virus-like across the Internet in July. In a genre-jumping twist, "This Land" made enough news that it received mega-exposure on TV and radio and turned the brothers into accidental experts in political marketing.

And how could it not have? It's the kind of marketing that campaign managers dream about: Whip up a sassy, silly video for a few thousand dollars and watch it spread at the speed of light until it's getting prominently displayed on TV. Say hello to Letterman, Leno and the whole battery of those popular morning "news" programs -- round-the-clock exposure for a fraction of what it would cost to buy that kind of screen time.

Gregg Spiridellis conceded that "This Land's" success was blind luck, as his and brother Evan's interest in politics is "far secondary to our interest in entertainment." Their previous videos -- including a brilliant hip-hop-style lesson on the Declaration of Independence -- take their cue from the 1970s Saturday-morning Schoolhouse Rock shorts like "I'm Just a Bill," but with a way bigger dose of hip. The Spiridellis' cartoons are fun and educational, but the brothers are not trying to make a career in politics.

That didn't seem to bother the organizers of the Politics Online Conference, where the key question is whether "This Land" can translate into the solid-tie/blue-blazer, baby-smooching, whistle-stop bread-and-butter strategies of the old-time politicos' playbooks.

Carol Darr, head of George Washington University's Democracy Online Project and the conference's organizer, said pictures -- especially video -- can work well to appeal to a candidate's or party's base.

"Pictures have the ability to be so much more inflammatory than most prose," said Darr. "A candidate's position paper, as much as they like to have them forwarded around, doesn't get forwarded a whole lot."

But can going irreverent with a "This Land" knock-off work for a real campaign? The videos that tend to metamorphose into viral miracles usually contain a jolly rage against the machine. One of the best examples is the irritated office worker whose humdrum life in the cubicle suddenly goes flying outward like the Big Bang as he throws his keyboard and monitor into the hallway and proceeds to beat them into plastic smithereens. Others contain a comical political incorrectness that suits bipartisan slam-jobs a la "This Land" -- but that kind of edginess could cut both ways in a tough race.

Matthew Dowd, the Bush-Cheney campaign's chief strategist in 2004, acknowledged that "the bigger campaigns always have to struggle with 'How far do you push the envelope?'"

Just look at the past 40 years. Lyndon Johnson's "Daisy" ad blew a few minds in 1964. It was controversial to be sure, but even those of us who weren't born yet know that ad. Walter Mondale's 1984 campaign against Ronald Reagan even went so far as to recycle the theme, using wide-eyed children contrasted with images of missiles and nuclear death and destruction, all to the tune of Crosby, Stills and Nash's "Teach Your Children."

But by and large, the big campaigns like to push the envelope gently, not rip it to pieces and hope everyone approves. Sometimes that's because confabbing at the top levels of campaign operations isn't always compatible with the mentality required to release quick hits in Internet time. Take too long to consider the ramifications and the whole project could go stale, said Jonah Seiger, co-founder of the ConnectionsMedia LLC online campaign shop and co-organizer of the conference.

Peter Daou, the man behind the Kerry-Edwards campaign's blogging operation, said the shelf-life of online cool -- usually shorter than that of a freckled banana -- bewilders some old-school campaign professionals. "A lot of people are not really familiar with exactly what all this is," Daou said. "Some are actually hostile to it."

And why wouldn't they be? The professionals know now that the Internet is an indispensable part of the campaign arsenal, and that it can provide huge returns for minor investments. But beyond viral marketing, online missteps can light a bonfire that burns down a campaign.

One example was the 2004 presidential campaign of former Vermont governor Howard Dean (D). Campaign manager Joe Trippi is legendary for mobilizing small-dollar contributions on the Internet to pull in $45 million, more money raised in that way than ever before. But the Internet also provided the echo chamber for the infamous "Dean Scream."

No, the scream didn't tear down the campaign; Dean did not "live and die by the Internet" as the conventional "wisdom" has it. Nevertheless, the media's -- and the blogging universe's -- fetishistic replay of that superficial event on the Web and TV irrevocably tinted Dean with the hue of "crazy loser." And a footnote: All those millions raised online couldn't substitute for his lack of deep grass-roots support in states like Iowa. The Web offered a nice illusion to the contrary, but it was just that.

So it's unsurprising that today's A-list campaign professionals would be wary. But that could change. The volunteers and professionals who ran campaign Internet operations in the 2004 elections doubtless will be back. If 2008 rolls around and everyone is using the Internet for what its primary political purpose appears to be in campaigns -- getting the edge -- it may not even be a realistic option to play it safe online. After all, any candidate whose chief handlers shy away from what might be tomorrow's trend du jour could be suspected of not really wanting to win.

But even the candidates willing to step over the precipice must realize that the best genius moments, from Archimedes to JibJab, are usually accidents. "This Land" is no exception, Spiridellis said. "All of a sudden this thing spread across the globe. We were at the center of something we never expected."

And maybe this is the lesson for attendees at this year's Politics Online Conference: The Internet is no panacea, and unintended consequences can take your candidate on an incredible online ride.

As Dowd said, "In political campaigns, the unplanned is usually as important or more important than the planned."

© 2005 TechNews.com

By Robert MacMillanwashingtonpost.com Staff WriterFriday, March 11, 2005; 8:57 AM

The Internet isn't referred to as the "online universe" for nothing. Like the universe, it embodies the quality of infinite expansion. And as both the universe and the Internet expand, they can produce works of colossal beauty and furious destruction with an alarming randomness.

So it goes with Internet politics. For nearly a decade now, the Internet has proved accommodating as well as frustrating to political imagemakers and idolmakers who puzzle over the question of how cyberspace can propel their candidates ahead of the competition and into office.

This question will rise again at the Politics Online Conference in Washington. The conference, in its 12th year, invites campaign professionals to thrash and hash over the best way to harness the Internet as the 21st-century candidate's ace of spades.

The roll of speakers and panelists usually consists of political professionals, online-journalism bigwigs and political bloggers. This year's gathering, which started Thursday afternoon and runs through today at The George Washington University in Washington, will see an unusual guest at this morning's session -- Gregg Spiridellis, who with brother Evan co-founded JibJab Inc. and co-composed (and co-performed) the animated music video "This Land Is Your Land."

Featuring cavorting caricatures of Sen. John F. Kerry and President Bush singing a demented version of the eponymous song, the cartoon ricocheted virus-like across the Internet in July. In a genre-jumping twist, "This Land" made enough news that it received mega-exposure on TV and radio and turned the brothers into accidental experts in political marketing.

And how could it not have? It's the kind of marketing that campaign managers dream about: Whip up a sassy, silly video for a few thousand dollars and watch it spread at the speed of light until it's getting prominently displayed on TV. Say hello to Letterman, Leno and the whole battery of those popular morning "news" programs -- round-the-clock exposure for a fraction of what it would cost to buy that kind of screen time.

Gregg Spiridellis conceded that "This Land's" success was blind luck, as his and brother Evan's interest in politics is "far secondary to our interest in entertainment." Their previous videos -- including a brilliant hip-hop-style lesson on the Declaration of Independence -- take their cue from the 1970s Saturday-morning Schoolhouse Rock shorts like "I'm Just a Bill," but with a way bigger dose of hip. The Spiridellis' cartoons are fun and educational, but the brothers are not trying to make a career in politics.

That didn't seem to bother the organizers of the Politics Online Conference, where the key question is whether "This Land" can translate into the solid-tie/blue-blazer, baby-smooching, whistle-stop bread-and-butter strategies of the old-time politicos' playbooks.

Carol Darr, head of George Washington University's Democracy Online Project and the conference's organizer, said pictures -- especially video -- can work well to appeal to a candidate's or party's base.

"Pictures have the ability to be so much more inflammatory than most prose," said Darr. "A candidate's position paper, as much as they like to have them forwarded around, doesn't get forwarded a whole lot."

But can going irreverent with a "This Land" knock-off work for a real campaign? The videos that tend to metamorphose into viral miracles usually contain a jolly rage against the machine. One of the best examples is the irritated office worker whose humdrum life in the cubicle suddenly goes flying outward like the Big Bang as he throws his keyboard and monitor into the hallway and proceeds to beat them into plastic smithereens. Others contain a comical political incorrectness that suits bipartisan slam-jobs a la "This Land" -- but that kind of edginess could cut both ways in a tough race.

Matthew Dowd, the Bush-Cheney campaign's chief strategist in 2004, acknowledged that "the bigger campaigns always have to struggle with 'How far do you push the envelope?'"

Just look at the past 40 years. Lyndon Johnson's "Daisy" ad blew a few minds in 1964. It was controversial to be sure, but even those of us who weren't born yet know that ad. Walter Mondale's 1984 campaign against Ronald Reagan even went so far as to recycle the theme, using wide-eyed children contrasted with images of missiles and nuclear death and destruction, all to the tune of Crosby, Stills and Nash's "Teach Your Children."

But by and large, the big campaigns like to push the envelope gently, not rip it to pieces and hope everyone approves. Sometimes that's because confabbing at the top levels of campaign operations isn't always compatible with the mentality required to release quick hits in Internet time. Take too long to consider the ramifications and the whole project could go stale, said Jonah Seiger, co-founder of the ConnectionsMedia LLC online campaign shop and co-organizer of the conference.

Peter Daou, the man behind the Kerry-Edwards campaign's blogging operation, said the shelf-life of online cool -- usually shorter than that of a freckled banana -- bewilders some old-school campaign professionals. "A lot of people are not really familiar with exactly what all this is," Daou said. "Some are actually hostile to it."

And why wouldn't they be? The professionals know now that the Internet is an indispensable part of the campaign arsenal, and that it can provide huge returns for minor investments. But beyond viral marketing, online missteps can light a bonfire that burns down a campaign.

One example was the 2004 presidential campaign of former Vermont governor Howard Dean (D). Campaign manager Joe Trippi is legendary for mobilizing small-dollar contributions on the Internet to pull in $45 million, more money raised in that way than ever before. But the Internet also provided the echo chamber for the infamous "Dean Scream."

No, the scream didn't tear down the campaign; Dean did not "live and die by the Internet" as the conventional "wisdom" has it. Nevertheless, the media's -- and the blogging universe's -- fetishistic replay of that superficial event on the Web and TV irrevocably tinted Dean with the hue of "crazy loser." And a footnote: All those millions raised online couldn't substitute for his lack of deep grass-roots support in states like Iowa. The Web offered a nice illusion to the contrary, but it was just that.

So it's unsurprising that today's A-list campaign professionals would be wary. But that could change. The volunteers and professionals who ran campaign Internet operations in the 2004 elections doubtless will be back. If 2008 rolls around and everyone is using the Internet for what its primary political purpose appears to be in campaigns -- getting the edge -- it may not even be a realistic option to play it safe online. After all, any candidate whose chief handlers shy away from what might be tomorrow's trend du jour could be suspected of not really wanting to win.

But even the candidates willing to step over the precipice must realize that the best genius moments, from Archimedes to JibJab, are usually accidents. "This Land" is no exception, Spiridellis said. "All of a sudden this thing spread across the globe. We were at the center of something we never expected."

And maybe this is the lesson for attendees at this year's Politics Online Conference: The Internet is no panacea, and unintended consequences can take your candidate on an incredible online ride.

As Dowd said, "In political campaigns, the unplanned is usually as important or more important than the planned."

© 2005 TechNews.com

Friday, March 11, 2005

Bart A. Ross, 57, killed himself when the police stopped his car. March 11, 2005 Electrician Says in Suicide Note That He Killed Judge's Family By JODI WILGOREN

HICAGO, March 10 - An out-of-work electrician whose delusional, decade-long legal crusade against doctors, lawyers and the government was dismissed last year by a federal judge, killed himself Wednesday night, leaving behind letters in which he admitted murdering the judge's husband and mother here last week. The man, Bart A. Ross, 57, had sued the federal government and a raft of others for $1 billion, saying they persecuted him with "Nazi-style" and terrorist tactics as he pursued a medical malpractice claim stemming from the severe disfigurement of his cancerous jaw. He left a suicide note in the van where he had been living confessing to the killings, and, in a letter to a local television station, said he had planned to assassinate the judge, Joan Humphrey Lefkow of Federal District Court, but "had no choice but to shoot" her loved ones when they discovered him hiding in the basement. Late Thursday night, David Bayless, a spokesman for the Chicago Police Department, said Mr. Ross's DNA matched that left on a cigarette butt in the Lefkows' sink, leaving little doubt about the case. "I regret killing husband and mother of Judge Lefkow as much as I regret that I have to die for the simple reason that they personally did me no wrong," said the lengthy letter signed by Mr. Ross and sent to WMAQ, NBC's Chicago affiliate, according to excerpts posted on the station's Web site. "After I shot husband and mother of Judge Lefkow, I had a lot of time to think about 'life and death' - killing is no fun, even though I knew I was already dead." Along with the confessional suicide note, the police said they found some 300 .22-caliber bullets, the same caliber used in the execution-style slayings, in the Plymouth van where Mr. Ross, who had no criminal record, shot himself in the head after being stopped for a missing tail light in the Milwaukee suburb of West Allis. Mr. Ross's death and admissions were a shocking turn in a vast investigation that had thus far focused on white supremacists. Superintendent Philip J. Cline of the Chicago police said Thursday that Mr. Ross's name was on a list of people, culled from Judge Lefkow's caseload, that investigators had planned to interview. He also said Mr. Ross resembled one of two composite sketches released two days after the killings, and that his account of leaving the Lefkows' home at 1:15 p.m. on Feb. 28 matched witness reports. The other sketch was of a younger man seen nearby in a red car that morning, but the chief said Thursday, "at no time did we say they were together." Until Wednesday night, the search had largely concentrated on sympathizers of Matthew Hale, the Aryan leader convicted last year of soliciting his security chief to kill Judge Lefkow. That the confessed killer was not part of an extremist group but one of many troubled litigants with pending matters left Mr. Hale's supporters seeking apologies and sent new waves of fear and insecurity through the jittery courthouse. Judge Lefkow, who expressed "sincere empathy" for Mr. Ross in legal papers even as she said his claims "lack any possible merit," described him in an interview Thursday as "a very pathetic, tragic person" and said the news was "very chilling." "I guess on one level I'm relieved that it didn't have anything to do with the white supremacy movement, because I feel my children are going to be safer," Judge Lefkow said as she left for Denver to bury her mother, Donna Humphrey. "It's heartbreaking that my husband and mother had to die over something like this." Neighbors of Mr. Ross, an electrical contractor who changed his name from Bartilomiej Ciszewski upon emigrating from Poland a quarter-century ago, said he was an angry loner whose huge black dog terrorized children on their quiet street in the Albany Park neighborhood of Chicago. They recalled his disrupting a block club meeting several years ago to solicit support for his suit, and said that early last month, facing eviction, he asked neighbors to adopt his dog and cat because he could no longer afford to feed them. Soon after, they said, he packed his belongings and left. "When I looked out this morning and saw all the police tape, I said to my husband, 'It has to be Bart Ross,' " said Jennifer Fernandez, a neighbor. "He obviously had a chip on his shoulder about this." Lawyers involved in the case, in which Mr. Ross represented himself, said that his physical and mental condition had deteriorated through the years and that they had fretted for their own safety around him. "Because he was delusional, he kept seeing bigger and bigger conspiracies," said Thomas L. Browne, who represented a law firm singled out by Mr. Ross, and said he immediately thought of him upon hearing of the Lefkow killings. "We really didn't think he was going to do anything violent, but he was getting less and less stable with all of these pleadings." Mr. Ross's ranting odyssey through the judicial system began in June 1994, two years after he was diagnosed with "squamous cell carcinoma of the floor of the mouth," according to court records, and originally focused on his complaints of botched surgery at the University of Illinois Hospital in Chicago. By the time his case reached Judge Lefkow's docket last year - having been thrown out of state court, dismissed by a different federal judge, and rejected by the United States Supreme Court - it had evolved into a tirade accusing the judiciary of treason and terrorism. Comparing his suit to those filed by relatives of victims in the Sept. 11 attacks, Mr. Ross sought $1 billion in damages, saying he had suffered "total financial destruction," having to sell his house, and "total destruction of every other aspect of his life over the past 12 years and in the foreseeable future." He said he had traveled 5,000 miles consulting 100 lawyers and 200 doctors, and that he had lost all his teeth, could no longer open his mouth more than a quarter-inch or eat solid food, and was "continuously 24/7 on pain relievers morphine and Tylenol with codeine." He sought the impeachment of judges involved in his case, and declared, somewhat incoherently, that "the same United States through judiciary is the Nazi-style criminal and violator of plaintiff's civil rights, and the same United States through the judiciary is the leader of the al-Qaeda style terrorist network." In a 2001 letter, Mr. Ross begged President Bush for help, though he noted that he had voted for Ralph Nader. "You all may regret it, if you Mr. President Bush avoid to make executive decision 'today' as 'tomorrow' will be too late," he wrote. Lawyers said Mr. Ross wore a sport coat over a sweater in court, and that his jaw got progressively thinner, practically preventing him from speaking aloud as the case wore on. One, Matthew Henderson, recalled Mr. Ross saying that "if he didn't get what he wanted, people were going to be sorry," while another, Barry Bollinger, remembered him making veiled threats like, "Somebody better take this seriously or things are going to happen." Mr. Bollinger said, "But I've heard that a thousand times in other cases." "This case was his life, and when it was over and he had nothing left to file," Mr. Bollinger said, his voice trailing off, "he had to be living in hell." Ruling against Mr. Ross's request to have a lawyer appointed to represent him at no charge, Judge Lefkow wrote: "The assigned judge expresses her sincere empathy with plaintiff's situation and by this brief decision does not intend to convey disregard for the cruel turn of fate plaintiff has experienced." But, she added, "the motion for appointment of counsel must be denied because the claims are certain to fail." At a news conference Thursday in West Allis, the police chief said one of his officers noticed Mr. Ross's van outside a school at 5 p.m. Wednesday, and followed him because the vehicle seemed suspicious. When the van stopped at a red light, the officer noticed a missing tail light and approached as a gunshot fired from inside exploded through the window. Finding the suicide note and other material linking Mr. Ross to the Lefkow murders, the police notified their Chicago counterparts and federal agents, who soon swarmed both the suburban street where the van remained and Mr. Ross's home in Chicago. In the letter to the television station, which ran four typed and three handwritten pages, Mr. Ross detailed the fateful day, saying he sneaked into the Lefkows' basement utility room at 4:30 a.m., and planned to lie in wait for the judge to return from work. "But Mr. Lefkow discovered me in the utility room about 9 a.m., he had an office next to the utility room," the letter says. "Then I heard voice 'Michael, Michael,' so I looked to the hallway (in the basement) and saw an older woman. I had to shoot her too. "I followed with a second shot to the head in both cases to minimize their suffering," he added. "Judge Lefkow was No. 1 to kill because she finished me off and deprive me to live my life through outrageous abuse of judicial power and decicration of the judicial office," the letter says. "Judge Lefkow, to her neighbors, is a church-going 'angel.' To me, Judge Lefkow is a Nazi-style criminal and terrorist." It is unclear why Mr. Ross was near Milwaukee, though several others vilified in his lawsuits live or work there. At the federal courthouse here, where judges have called for increased security, the news was greeted with relief and trepidation. "We all have these people, we all have people who are potentially unstable," another judge, Robert W. Gettleman, said.. "Of course, for something like this to happen, it's so over the top, nobody ever would have predicted it." Because of Mr. Hale's conviction for plotting to kill Judge Lefkow, much of the attention in the last week had fallen on him and his supporters. He faces up to 40 years at his sentencing on April 6. Mr. Hale's father, Russell, said, "It's a great relief to us that they found out, hopefully, who did this." "I'm sorry for the person's family that did do this," Mr. Hale added. "Somebody loved that person, and it is too bad that it happened." Billy Roper, a friend of Mr. Hale's who runs the Web site whiterevolution.com

Friday, March 11, 2005

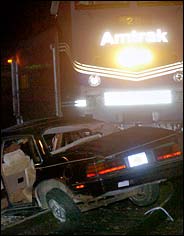

Remains of a truck struck by a train at a Roseland, La., crossing on Sunday. Four people were killed. Most rail crossings lack lights or gates, and rail safety advocates say overbilling is limiting how many can be installed. February 18, 2005. Oversight Is Spotty on Rail-Crossing Safety Projects By WALT BOGDANICH and JENNY NORDBERG

hen Missouri state auditors set out to learn if railroads were prudently spending government money to install warning signals at grade crossings, they found more than a few problems. According to audit reports from two years ago, one railroad, Kansas City Southern, had submitted overcharges of nearly 100 percent, or almost $60,000, on one project. Another, BNSF Railway, also had an overcharge of nearly 100 percent. And that was not all. BNSF, formerly known as Burlington Northern and Santa Fe, overcharged to a lesser degree on more than a dozen other signal projects, records show. Missouri officials should not have been surprised. In 2000, Missouri asked BNSF to repay $670,000 in overcharges on 43 earlier signal projects, all financed mostly by the Federal Highway Administration. Another railroad had similar overcharges, state officials said. When it comes to catching sizable overcharges in the federally financed lights-and-gates program, Missouri stands out. Other states audit only a few signal projects - or none - even though these construction contracts are almost always awarded to railroads without competitive bids, according to public records and government officials. The result, rail safety advocates say, is that signals often cost more than they should, which means that fewer of these life-saving warning devices are installed. Safety experts say warning lights and gates are a major reason why crossing deaths have declined in recent years, though they did jump in 2004. Even so, most of the nation's 150,000 rail crossings on public roads have no lights or gates. In all, nearly 900 people have died at crossings that lack lights or gates since 2000. Just this week, separate fatal accidents occurred at two crossings with no lights or gates in Tangipahoa Parish in Louisiana; the first, on Sunday, killed one man and three children, while the second crash killed two men yesterday. But while up to 700 crossings in Louisiana need warning lights and gates, said Mark Lambert, a state transportation official, there is not enough federal money to pay for them. Louisiana has questioned railroad billings, and last year, auditors there found possible overcharges of more than 10 percent, about $1.1 million, though the actual recovery might drop after settlement discussions. "If you are spending the public's money, you would rather see a competitive situation," said Steven L. Schooner, co-director of the Government Procurement Law Program at George Washington University Law School. The Federal Highway Administration agrees, but only up to a point. When building a road, the agency calls competitive bidding "a basic fundamental principle of federal procurement law." But that does not hold for the lights-and-gates program, where federal highway officials have spent $1.7 billion since 1973 to make grade crossings safer. "Bidding or no bidding, post-performance auditing, or at least some level of oversight, is necessary to ensure proper stewardship of taxpayer funds," Mr. Schooner said. A spokesman for the highway administration, Brian Keeter, said that to make sure states "use federal funds appropriately," they are required to report on the progress of crossing projects and whether they have helped to reduce accidents. But in written responses to questions, he did not specifically answer how the government could ensure that those funds are used properly if many projects are not audited. Mr. Keeter also did not provide the percentage of projects that are audited. Federal rules do not require states, which administer the lights-and-gates program, to seek competitive bids as long as railroads manage the projects. While states can seek bids from private contractors if they run the projects themselves, they prefer to let railroads handle the work, since they own the crossings and are obligated to maintain them. "On the highway, we can do what we want," said Lamar McDavid, an auditor with the Alabama Transportation Department. "But we're on private property, so we have to do what they want." Keith Golden of the Georgia Transportation Department added, "We don't have the power to negotiate with them." States said they do negotiate prices with railroads. In Tennessee, after a 17-year-old girl was killed at a rail crossing in 1997, the state told CSX to install gates there. The railroad said it would cost $122,000, nearly three times what the state thought was fair, according to state records. CSX eventually agreed to do the work for half its original proposal. The upgrade was finished in 1999. Today, a full set of lights and gates costs $80,000 to $200,000 or more, depending on the crossing, state transportation officials said. The federal government does not require states to audit every project. "States perform the day-to-day oversight of this program and thus determine when or if audits occur," said Doug Hecox, a Federal Highway Administration spokesman. The Association of American Railroads, a trade group, said railroads did not make a profit on lights and gates. And, the association added, "Taxpayers can be assured that they are getting the best price possible because states conduct audits." But Ohio, for example, does no audits of signal projects at grade crossings, state officials said. Officials in other states said they feared that some audits were becoming less reliable. Because one major railroad - Norfolk Southern - is moving toward a paperless work environment, verifying bills is becoming "nearly impossible," according to a joint audit in 2003 involving 10 states, including New York. The rail association said its members are not violating federal reimbursement rules. Railroads said overcharges were simply unintentional mistakes, a statement not disputed by state auditors. Kansas City Southern, for example, said its overbillings were generally small and due to the complexity of different state contracts. BNSF said Missouri's audit findings were the result of misunderstandings. And while the railroad did not always agree with the state's findings, BNSF said it reimbursed the state anyhow. It is also true that two separate joint audits, representing 8 Eastern states in one group and 10 in another, found only minimal overcharges by CSX and Norfolk Southern. But these joint audits covered only a tiny percentage of projects, fewer than 10 projects in all from the participating states. And those reviews are not done every year, records show. CSX, for example, has not undergone a joint audit by the group of Eastern states since 2000, in part because auditors said they did not expect to find significant problems. An official with the federal Department of Transportation's inspector general said he was unaware of any comprehensive investigation by his office of the federal lights-and-gates program. But when the inspector general followed up on a whistle-blower complaint in the 1990's, investigators found that CSX had knowingly padded its expenses. CSX agreed in 1995 to pay $5.9 million to settle civil fraud accusations. In addition to federal funds, state money is also used in signal programs. California, for example, pays railroads for maintaining lights and gates at crossings after they are installed. But when state officials checked these billings, they found that railroads had submitted expenses for maintaining signals at crossings that were closed, crossings with no warning signals, crossings with no rail service, and crossings claimed by more than one railroad. As a result, California officials rejected $346,492 in 2003. Illinois officials also use state money to pay railroads for upgrading rail crossings. But in a highly critical report in November 2003, the Illinois auditor general found that even though state transportation officials had said railroad bills "seemed unreasonably high," they still did not verify charges for materials, labor or personnel expenses. Railroads, for example, submitted bills for trench-digging equipment that was rented for weeks - even months - longer than necessary, the report found. State officials, the report added, do "not assure the prescribed work is done, work is done on schedule or that expenditures for the project are appropriate." The projects sampled by the auditor general took nearly four years to complete. Copyright 2005

Friday, March 11, 2005

A car-train accident at a crossing in Charlotte, Mich., killed Melanie Pouch and her 15-year-old daughter, Meghann, in April. Witnesses said the Amtrak train had entered the crossing when the gates came down. DEATH ON THE TRACKS Questions Raised on Signals at Rail Crossings By WALT BOGDANICH