Saturday, June 04, 2005

Richard McGuire

June 5, 2005

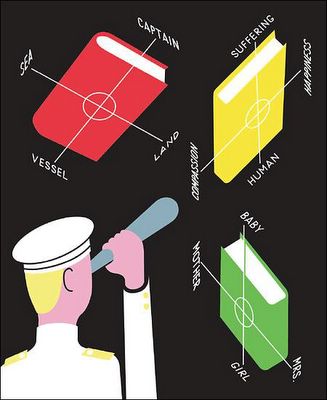

The Word Crunchers

By DEBORAH FRIEDELL

In David Lodge's 1984 novel, ''Small World,'' a literature professor fond of computer programming presents a novelist with a fantastic discovery: by entering all the novelist's books into a computer, the professor can determine the novelist's favorite word. The computer knows to ignore the mortar of sentences -- articles, prepositions, pronouns -- to get to ''the real nitty-gritty,'' Lodge writes, ''words like love or dark or heart or God.'' But the computer's conclusion causes the novelist to shrink from ever writing again. His favorite word, it finds, is ''greasy.''

Two decades later, Amazon.com, improving on its popular ''search inside the book'' function, in April introduced a concordance program, whereby a click of the mouse reveals a book's most frequently occurring words, ''excluding common words.'' Further clicks reveal their contexts. And so we learn that the nitty-gritty words appearing most frequently in the King James Bible include ''God,'' ''Lord,'' ''shall'' and ''unto.'' The word that appears most frequently in T. S. Eliot's ''Collected Poems'' is ''time'' -- ''There will be time, there will be time'' -- while the word that turns up most frequently in ''Extraordinary Golf,'' by Fred Shoemaker and Pete Shoemaker, is, illuminatively, ''golf.''

Such computer tools have been centuries in the making. As the legend goes, the first concordance -- of the Vulgate, completed in the early 13th century -- required the labor of 500 Dominican friars. Even in more modern times, those who began concordances knew that they might not live long enough to see them completed. This was the case for the first directors of the Chaucer concordance, which took 50 years before reaching publication in 1927.

In order to speed the process for his Wordsworth concordance, first published in 1911, the scholar Lane Cooper required an army of Cornell graduate students and faculty wives. It was a laborious undertaking, involving glue, rubber stamps and a vastly intricate system of cross-referenced 3-by-5 cards.

At the same time Cooper was mapping ''The Prelude,'' biologists at other universities were discovering sex chromosomes. Indeed, in his description of the alphabetization and arrangement involved in concordance-making, Cooper calls to mind a profession that was only just beginning to exist. He is a geneticist of language, isolating and mapping the smallest parts with the confidence that they will somehow reveal the design of the whole.

In 1951, I.B.M. helped create an automated concordance that cataloged four hymns by St. Thomas Aquinas. The scanning equipment was primitive. Words still had to be hand-punched onto cards, programs for alphabetizing had to be written, and many found the computers more trouble than they were worth. Even with electronic assistance, indexing all of Aquinas took a million man-hours and 30 years before it was finally completed in 1974.

Yet even as computers grew more sophisticated, some scholars resisted them. In 1970, Stephen M. Parrish, an English professor, described how when he ''proposed to some of the Dante people at Harvard that they move to the computer and finish the job in a couple of months, they recoiled in horror.'' In their system, ''each man was assigned a block of pages to index lovingly,'' and had been doing so contentedly for more than 25 years. But eventually, of course, concordance makers joined the ranks of all the other noble occupations gone.

Why did they labor so? Monks used concordances to ferret out connections among the Gospels. Christian theologians relied on them in their quest for proof that the Old Testament contained proleptic visions of the New. For philologists, concordances provide a way of defining obscure words; if you gather enough examples of a word in context, you may be able to divine its meaning. Similarly, concordances help scholars attribute texts of uncertain provenance by allowing them to see who might have used certain words in a certain way. For readers, concordances can be a guide into a writer's mind. ''A glance at the Lane Cooper concordance'' led Lionel Trilling to conclude that Wordsworth, ''whenever he has a moment of insight or happiness, talks about it in the language of light.'' (The concordance showed the word ''gleam'' as among Wordsworth's favorites).

Sometimes a word's infrequent appearance can be just as revealing. In the 1963 concordance to Yeats compiled by Parrish and James A. Painter, Painter singles out the opening stanza of ''Byzantium,'' italicizing words that appear nowhere else in Yeats's poems:

The unpurged images of day recede;

The Emperor's drunken soldiery are abed;

Night resonance recedes, night-walkers' song

After great cathedral gong;

A starlit or a moonlit dome disdains

All that man is,

All mere complexities,

The fury and the mire of human veins.

Other words -- ''abed'' ''soldiery,'' ''gong,'' ''starlit,'' ''dome'' -- appear throughout Yeats's work only once or twice. ''It is almost as though on these occasions Yeats rose to a fresh level of poetic discourse,'' Painter wrote.

But what about words not worth cataloging because they are so common? The Milton concordance edited by Charles D. Cleveland, for example, omits most prepositions in the poem, but that doesn't mean you should ignore their workings. Milton, as the scholar Leslie Brisman has observed, is ''everywhere concerned with the act of choosing.'' ''Paradise Lost'' is obsessed with alternatives to temptation, with finding different ways of seeing and thinking, and its language mirrors this preoccupation. Thus, Milton describes God's perfect view of Earth, unlike ''when by night the Glass / of Galileo, less assu'rd, observes / Imagin'd Lands and Regions in the Moon.'' But then he continues with other metaphorical options: ''Or Pilot from amidst the Cyclades / Delos or Samos first appearing kens / A cloudy spot.'' In the Miltonic metaphor, one of Cleveland's rejected words, ''or,'' might be the most important.

To read a concordance is to enter a world in which all the included words are weighted equally, each receiving just one entry per appearance. While Amazon's concordance can show us the frequency of the words ''day'' and ''shall'' in Whitman, ''contain'' and ''multitudes'' don't make the top 100. Neither does ''be'' in Hamlet, nor ''damn'' in ''Gone with the Wind.'' The force of these words goes undetected by even the most powerful computers.

Yet this has not stopped Amazon from introducing another new feature alongside its concordance -- ''statistically improbable phrases,'' which promises to detect ''the most distinctive phrases in the text of books in the Search Inside! program.'' Apparently it uses an algorithm that compares a book's word orders to the word orders of all the other books that offer the Search Inside! program. As for its efficacy, suffice it to say that Amazon claims that ''retrospective arrangement'' and ''editor cried'' are among the most distinctive phrases in ''Ulysses.''

Once it would have seemed unnecessary to point out that a statistical tool has no ear for allusions, for echoes, for metrical and musical effects, for any of the attributes that make words worth reading. Today, perhaps it bears reminding.

Deborah Friedell is assistant literary editor of The New Republic.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Contact Us Back to Top