Friday, April 08, 2005

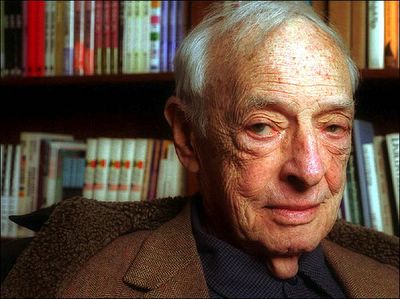

Saul Bellow, creator of larger-than-life fictional characters, in 2001.

April 6, 2005

Saul Bellow, Who Breathed Life Into American Novel, Dies at 89

By MEL GUSSOW and CHARLES McGRATH

Saul Bellow, the Nobel laureate and self-proclaimed historian of society whose fictional heroes - and whose scathing, unrelenting and darkly comic examination of their struggle for meaning - gave new immediacy to the American novel in the second half of the 20th century, died yesterday at his home in Brookline, Mass. He was 89.

His death was announced by Walter Pozen, Mr. Bellow's lawyer and a longtime friend.

"I cannot exceed what I see," Mr. Bellow said. "I am bound, in other words, as the historian is bound by the period he writes about, by the situation I live in." But his was a history of a particular and idiosyncratic sort.

The center of his fictional universe was Chicago, where he grew up and spent most of his life, and which he made into the first city of American letters. Many of his works are set there, and almost all of them have a Midwestern earthiness and brashness. Like their creator, Mr. Bellow's heroes were all head and all body both. They tended to be dreamers, questers or bookish intellectuals, but they lived in a lovingly depicted world of cranks, con men, fast-talking salesmen and wheeler-dealers.

In novels like "The Adventures of Augie March," his breakthrough novel in 1953, "Henderson the Rain King" and "Herzog," Mr. Bellow laid a path for old-fashioned, supersized characters and equally big themes and ideas. As the English novelist Malcolm Bradbury said, "His fame, literary, intellectual, moral, lay with his big books," which were "filled with their big, clever, flowing prose, and their big, more-than-lifesize heroes - Augie Marches, Hendersons, Herzogs, Humboldts - who fought the battle for courage, intelligence, selfhood and a sense of human grandeur in the postwar age of expansive, materialist, high-towered Chicago-style American capitalism."

Mr. Bellow said that of all his characters Eugene Henderson, of "Henderson the Rain King," a quixotic violinist and pig farmer who vainly sought a higher truth and a moral purpose in life, was the one most like himself, but there were also elements of the author in the put-upon, twice-divorced but ever-hopeful Moses Herzog and in wise but embattled older figures like Artur Sammler, of "Mr. Sammler's Planet" and Albert Corde, the dean in "The Dean's December." They were all men trying to come to grips with what Corde called "the big-scale insanities of the 20th century."

At the same time, some of his novellas and stories were regarded as more finely wrought. V. S. Pritchett said, "I enjoy Saul Bellow in his spreading carnivals and wonder at his energy, but I still think he is finer in his shorter works." Pritchett considered Mr. Bellow's 1947 book "The Victim" "the best novel to come out of America - or England - for a decade" and thought that "Seize the Day," another shorter book, was "a small gray masterpiece."

All his work, long and short, was written in a distinctive, immediately recognizable style that blended high and low, colloquial and mandarin, wisecrack and aphorism, as in the introduction of the poet Humboldt at the beginning of "Humboldt's Gift": "He was a wonderful talker, a hectic nonstop monologuist and improvisator, a champion detractor. To be loused up by Humboldt was really a kind of privilege. It was like being the subject of a two-nosed portrait by Picasso, or an eviscerated chicken by Soutine."

Mr. Bellow stuck to an individualistic path, and steered clear of cliques, fads and schools of writing. He was frequently lumped together with Philip Roth and Bernard Malamud as a Jewish-American writer, but he rejected the label, saying he had no wish to be part of the "Hart, Schaffner & Marx" of American letters. In his younger days, he was loosely allied with the liberal and arty Partisan Review crowd, led by Philip Rahv and William Phillips, but he eventually broke with them saying, "They want to cook their meals over Pater's hard gemlike flame and light their cigarettes at it." He spoke his own mind, without regard for political correctness or fashion, and was often involved, at least at a literary distance, in fierce debates with feminists, black writers, postmodernists.

On multiculturalism, he was once quoted as asking: "Who is the Tolstoy of the Zulus? The Proust of the Papuans?" The remark caused a furor and was taken as proof, he said, "that I was at best insensitive and at worst an elitist, a chauvinist, a reactionary and a racist - in a word, a monster." He later said the controversy was "the result of a misunderstanding that occurred (they always do occur) during an interview."

In his life as in his work, he was unpredictable. He was the most urban of writers and yet he spent much of his time at a farm in Vermont. He admired and befriended the Chicago machers - the deal-makers and real-estate men - and he dressed like one of them, in bespoke suits, Turnbull & Asser shirts and a Borsalino hat. He was a devoted, self-taught cook, as well as a gardener, a violinist and a sports fan.

He was a great admirer of, among others, John Cheever, William Faulkner, Ralph Ellison (a close friend), Cormac McCarthy, Denis Johnson, Joyce Carol Oates and James Dickey. Mr. Bellow grew up reading the Old Testament, Shakespeare and the great 19th-century Russian novelists and always looked with respect to the masters, even as he tried to recast himself in the American idiom. A scholar as well as teacher, he read deeply and quoted widely, often referring to Henry James, Marcel Proust and Gustave Flaubert. But at the same time he was apt to tell a joke coined by Henny Youngman.

While others were ready to proclaim the death of the novel, he continued to think of it as a vital form. "I never tire of reading the master novelists," he said. "Can anything as vivid as the characters in their books be dead?"

Once, with reference to Flaubert, he wrote, "I think novelists who take the bitterest view of our modern condition make the most of the art of the novel," and added, "The writer's art appears to seek a compensation for the hopelessness or meanness of existence.

"Saul Bellow was a kind of intellectual boulevardier, wearing a jaunty hat and a smile as he marched into literary battle. In spite of - or perhaps, because of - his lofty position, he was criticized more than many of his peers. In reviews his books were habitually weighed against one another. Was this one as full-bodied as "Augie March"? Where was the Bellow of old? Norman Mailer said that "Augie March," Mr. Bellow's grand bildungsroman, was unconvincing and overcooked; Elizabeth Hardwick thought that in "Henderson," he was trying too hard to be an important novelist. He was prickly but also philosophical: "Every time you're praised, there's a boot waiting for you. If you've been publishing books for 50 years or so, you're inured to misunderstanding and even abuse."

Years ago, at the Breadloaf Writers Conference in Vermont, he spent a great deal of time with Robert Frost. "I thought when I was his age," he said, "people would let me get away with murder, too. But I'm not allowed to get away with a thing." Smiling, he vowed, "My turn will come."

Taking His Success in Stride

In a long and unusually productive career, Mr. Bellow dodged many of the snares that typically entangle American writers. He didn't drink much, and though he was analyzed four times, and even spent some time in an orgone box, his mental health was as robust as his physical health. His success came neither too early nor too late, and he took it more or less in stride. He never ran out of ideas and he never stopped writing.

The Nobel Prize, which he won in 1976, was the cornerstone of a career that also included a Pulitzer Prize, three National Book Awards, a Presidential Medal and more honors than any other American writer. In contrast with some other winners, who were wary of the albatross of the Nobel, Mr. Bellow accepted it matter-of-factly. "The child in me is delighted," he said. "The adult in me is skeptical." He took the award, he said, "on an even keel," aware of "the secret humiliation" that "some of the very great writers of the century didn't get it."

This most American of writers was born in Lachine, Quebec, a poor immigrant suburb of Montreal, and named Solomon Bellow, his birthdate is listed as either June or July 10, 1915, though his lawyer, Mr. Pozen, said yesterday that Mr. Bellow customarily celebrated in June. (Immigrant Jews at that time tended to be careless about the Christian calendar, and the records are inconclusive.)

He was the last of four children, but as he was always quick to point out, the first to be born in the New World. His parents had emigrated from Russia two years before, though in Canada their luck wasn't much better. Solomon's father, Abram, failed at one enterprise after another. His mother, Liza, was deeply religious and wanted her youngest child, her favorite, to become either a rabbi or a concert violinist. But Mr. Bellow's fate was sealed, or so he later claimed, when at the age of 8 he spent six months in Ward H of the Royal Victoria Hospital, suffering from a respiratory infection and reading "Uncle Tom's Cabin" and the funny papers. It was there, he said, that he discovered his sense of destiny - his certainty that he was meant for great things.

In 1924, when their son was 9, the Bellows moved to Chicago, where the family began to prosper a little as Abram picked up work in a bakery, delivering coal, and even bootlegging. The family continued its old ways in the United States, and during his childhood, Saul was steeped in Jewish tradition.

Eventually he rebelled against what he considered to be a "suffocating orthodoxy" and found in Chicago not just a physical home but a spiritual one. Recalling his sense of discovery and of belonging, he later wrote, "The children of Chicago bakers, tailors, peddlers, insurance agents, pressers, cutters, grocers, the sons of families on relief, were reading buckram-bound books from the public library and were in a state of enthusiasm, having found themselves on the shore of a novelistic land to which they really belonged, discovering their birthright ... talking to one another about the mind, society, art, religion, epistemology and doing all this in Chicago, of all places." Eventually Chicago became for him what London was for Dickens and Dublin was for Joyce - the center of both his life and his work, and not just a place or a background but almost a character in its own right.

He began writing in grammar school, alongside his childhood friend Sydney J. Harris, later a Chicago newspaper columnist: "We would sit at the Harrises' dining room table and write things to each other - any old thing." His father was disapproving, and remained so for decades. "You write and then you erase," he said when Mr. Bellow was in his 20's. "You call that a profession?"

His mother was more supportive, but when Saul was 17, she died, a loss that he found difficult to overcome. With her death and his father's remarriage, he said, "I was turned loose - freed, in a sense: free but also stunned, like someone who survives an explosion but hasn't yet grasped what has happened." He added, "It was disabling for me for a couple of years."

In 1933 he began college at the University of Chicago, but two years later transferred to Northwestern, because it was cheaper. He had hoped to study literature but was put off by what he saw as the tweedy anti-Semitism of the English department, and graduated in 1937 with honors in anthropology and sociology, subjects that were later to instill his novels. Bu he was still obsessed by fiction. While doing graduate work in anthropology at the University of Wisconsin, he found that "every time I worked on my thesis, it turned out to be a story." He added: "I sometimes think the Depression was a great help. It was no use studying for any other profession."

Quitting his graduate studies at Wisconsin after several months, he participated in the W.P.A. Federal Writers' Project in Chicago, preparing biographies of Midwestern novelists, and later joined the editorial department of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, where he worked on Mortimer Adler's "Great Books" series.

He came to New York "toward the end of the 30's, muddled in the head but keen to educate myself." While living in Greenwich Village and writing fiction, aimlessly and with little success at first, he also reviewed books. When World War II began he was rejected by the Army because of a hernia; he later joined the merchant marine and was in training when the atom bomb was dropped on Hiroshima. During his service, he finished writing "Dangling Man," about the alienation of a young Chicagoan waiting to be drafted. It was published in 1944, before the author was 30, and was followed by "The Victim," a novel about anti-Semitism that was written, he said, under the influence of Dostoyevsky. Mr. Bellow later called these novels his "M.A. and Ph.D." They were apprentice work, he believed, finely written but weak in plot and too much in thrall to European models.

Epiphany in Paris

In 1948, financed by a Guggenheim fellowship, Mr. Bellow went to Paris, where, walking the streets of Paris and thinking about his future, he had a kind of epiphany. He remembered a friend from his childhood named Chucky, "a wild talker who was always announcing cheerfully that he had a super scheme," and he began to wonder what a novel in Chucky's voice would sound like. "The book just came to me," he said later. "All I had to do was be there with buckets to catch it."

The resulting novel, "The Adventures of Augie March," was published in 1953, and it became Mr. Bellow's breakthrough, his first best seller and the book that firmly established him as a writer of consequence. The beginning of the novel was as striking and as unforgettable as the beginning of "Huckleberry Finn," and it announced a brand-new voice in American fiction, jazzy, brash, exuberant, with accents that were both Yiddish and Whitmanian:

"I am an American, Chicago born - Chicago, that somber city - and go at things as I have taught myself, free-style, and will make the record in my own way: first to knock, first admitted; sometimes an innocent knock, sometimes a not so innocent."

"Fiction is the higher autobiography," Mr. Bellow once said, and in his subsequent novels, he often adapted facts from his own life and the lives of people he knew. Humboldt was a version of the poet Delmore Schwartz; Henderson was based on Chandler Chapman, a son of the writer John Jay Chapman; Gersbach, the cuckolder in "Herzog," was a Bard professor named Jack Ludwig, who did indeed seduce Mr. Bellow's wife at the time; and in one guise or another most of Mr. Bellow's many girlfriends all turned up.

"What a woman-filled life I always led," says Charlie Citrine, the protagonist of "Humboldt's Gift." Those are words that could have been echoed by the author who had almost innumerable affairs and was married five times. His wives were Anita Goshkin, Alexandra Tsachacbasov, Susan Glassman, Alexandra Ionescu Tulcea and Janis Freedman. All of Mr. Bellow's marriages but his last ended in divorce. In addition to his wife Janis, he is survived by three sons, Gregory, Adam and Daniel; a daughter, Naomi Rose; and six grandchildren.

A Turning Point

With "Henderson the Rain King" in 1959, Mr. Bellow envisioned an even more ambitious canvas than that of "Augie March," with the story of an American millionaire who travels in Africa in search of regeneration. Mr. Bellow, who had never been to Africa, regarded that novel as a turning point. "Augie March," he said later, was a little unruly and out of control; with "Henderson" he had full command of his creative powers.

"Henderson" was followed in 1964 by "Herzog," with the title character a Jewish Everyman who is cuckolded by his wife and his best friend. "He is taken by an epistolary fit," said the author, "and writes grieving, biting, ironic and rambunctious letters not only to his friends and acquaintances, but also to the great men, the giants of thought, who formed his mind."

Looking back on the writing of that book, he said: " 'Herzog' was just a brainstorm. One day I found myself writing letters - all over the place. Then it occurred to me that it was a very good idea for writing a book about the mental condition of the country and of its educated class." The novel won a National Book Award.

In contrast, that same year "The Last Analysis" (one of several plays by Mr. Bellow) opened on Broadway and was a quick failure. "It started as a lark," he said, "but it ended as an ostrich."

With "Mr. Sammler's Planet" in 1969, a novel about a survivor of the Holocaust living and ruminating in New York, Mr. Bellow won his third National Book Award. "Humboldt's Gift," in 1975, proved to be one of his greatest successes. In it, Charlie Citrine, a Pulitzer Prize-winning writer, has to come to terms with the death of his mentor, the poet Von Humboldt Fleischer.

Life imitated art in this case, and "Humboldt" won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. The Nobel Prize in Literature soon followed, with the Royal Swedish Academy citing his "exuberant ideas, flashing irony, hilarious comedy and burning compassion," and Mr. Bellow was now placed in a class with his American predecessors Ernest Hemingway and William Faulkner.

"After I won the Nobel Prize," he said, "I found myself thrust in the position of a public servant in the world of culture. I was supposed to seem benevolent and to pontificate and bless with my presence - elder statesman whether I liked it or not. The price you have to pay."

His first book following the Nobel was "To Jerusalem and Back," a nonfiction memoir about his trip to Israel. That was followed by "The Dean's December," a novel about the decay of the American city; the short-story collection "Him With His Foot in His Mouth" and, in 1987, the novel "More Die of Heartbreak." From then on, through "The Bellarosa Connection" and "The Actual," his books became shorter and shorter, a case of Mr. Bellow sending out what he called "a briefer signal."

With "Ravelstein" (2000), he returned to longer fiction. Inspired by the life of his close friend Allan Bloom, the author of "The Closing of the American Mind," the book dealt with a celebrated professor dying of AIDS. In his review in The New York Times Book Review, Jonathan Wilson said it was "a great novel of that much-maligned item, American male friendship."

Leaving Chicago

In 1993, after many years of living in Chicago and teaching at the University of Chicago, he left his adopted city. The reasons for his departure were complex. Several of his close Chicago friends had died, among them Allan Bloom, and Mr. Bellow said he "got tired of passing the houses of my dead friends." He was also upset by the ugly racial climate in Chicago at the time. A few people in the radical black community tried to spread a story that Jewish doctors were deliberately infecting black children with H.I.V., and Mr. Bellow objected to this "blood libel" in an article printed in The Chicago Tribune.

He moved to Boston and, at the invitation of the chancellor, John Silber, began teaching at Boston University. Explaining why he continued to teach, even though he was one of the most financially successful of serious American novelists, he said: "You're all alone when you're a writer. Sometimes you just feel you need a humanity bath. Even a ride on the subway will do that. But it's much more interesting to talk about books. After all, that's what life used to be for writers: they talk books, politics, history, America. Nothing has replaced that."

In 1994, while on a Caribbean vacation with his wife in St. Martin, Mr. Bellow became sick after eating a toxic fish, and almost died - an incident that is also recounted in "Ravelstein." After a long recovery process, he returned to his writing, with "By the St. Lawrence," a story evoking a traumatic memory of his childhood.

Throughout Mr. Bellow's life, his approach to his art was that of an alien newly arrived on earth: "I've never seen the world before. Now I was seeing it, and it's a beautiful, marvelous gift. Enchanting reality! And when the end came, I was told by the cleverest people I knew that it would all vanish. I'm not absolutely convinced of that. If you asked me if I believed in life after death, I would say I was an agnostic. There are more things between heaven and earth, Horatio, etc."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top