Friday, June 24, 2005

June 24, 2005

The Outtakes of Brando's Large Life

By CARYN JAMES

Hidden in one of the Japanese imitation-lacquer boxes that belonged to Marlon Brando and that will be auctioned at Christie's next week are a few of his little treasures: a plastic bagel that, when lifted, reveals a big plastic cockroach; a fake finger, bloodied at one end; and other pint-size practical jokes. It's not exactly a surprise that one of the greatest actors of our time was also a joker. We might have guessed that from some of his bizarre public appearances, like the television interview, from his bloated and nonsensical later years, in which he kissed Larry King on the mouth. And Johnny Depp, in a brief remembrance written for the Christie's catalog, lovingly recalls his friend's childlike sense of humor, with memories that are largely about whoopee cushions.

Still, it's a jolt to see the evidence in the stuff he left behind. And much of what is for sale does seem like stuff, leftover odds and ends desirable only because Brando touched them. (The public can view the items, all 320 lots of them, beginning tomorrow at Christie's. The auction is on Thursday.)

There is nothing exquisite, and certainly nothing that says "movie star," about the furniture removed from Brando's house on Mulholland Drive after he died last year at 80. It includes an ordinary brown leather couch and some weathered wooden garden chairs.

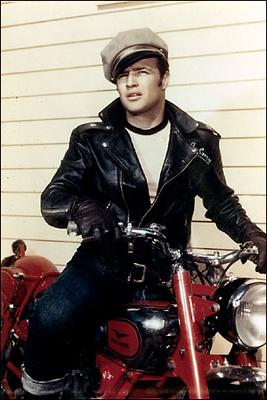

There are more intriguing personal objects that clearly meant something to him: conga drums, which he became passionate about playing when he was an unimaginably brilliant, intense and gorgeous young actor in the 1950's; a small American Indian dreamcatcher that hung over his bed.

But the true riches in this sale are his papers, an invaluable cache of film scripts annotated with his comments, along with letters to him from Mario Puzo, Jack Kerouac and Francis Ford Coppola. The film-related material was not found in the house, but was stashed in storage buildings on the grounds, the way other people might toss an old bike in a garage. The papers were, after all, relics of his glory days.

The question that haunts Brando's life is: What went wrong? Why did an actor of such genius throw his art away, twice? The first downslide began with his self-indulgence on the set of 1962's "Mutiny on the Bounty"; and his 70's comeback in "The Godfather" and "Last Tango in Paris" led to the second decline, into ballooning weight and junk roles taken only for money.

His possessions and even his papers don't begin to explain that, but the objects on sale offer detailed evidence of both the artist and the guy who loved whoopee cushions. Two items have generated the most inquiries, Christie's says: Brando's annotated script for "The Godfather" and the Foosball table from his den.

Brando knew that celebrity tchotchkes don't reveal much. "Fame has been the bane of my life, and I would have gladly given it up," he wrote in his cockeyed but often illuminating memoir, "Brando: Songs My Mother Taught Me." Because of celebrity, he wrote, "People don't relate to you as the person you are, but to a myth they believe you are, and the myth is always wrong."

What is on display at Christie's does not reveal the man behind the myth, but the elements that make up that myth, organized into neat little lots reflecting what we know (or think we know) about his taste and social causes. So here is the Brando who championed the rights of the American Indian: there's a headdress, turquoise jewelry, a fringed coat and a vest, as well as a photograph of Brando wearing that vest. Here is the Brando with an affinity for Asia, evident in a collection of small statues, including two Buddhas, some kept in a shrine-like recess in a wall of his bedroom. There are shells and bits of coral from the Tahitian atoll he owned, and an aerial photograph of that island. These ordinary objects reinforce our kaleidoscopic image of the many Brandos. (There is a collection of eight kaleidoscopes for sale, too.)

Even the silliest film memorabilia are more eloquent because they could have belonged only to him. A leather belt inscribed "Mighty Moon Champion" in big bright colors was a gift from his co-stars on the set of "The Godfather," where Brando, James Caan and Robert Duvall amused themselves by mooning one other.

Because his performance in "The Godfather" was so enduring and iconic, there is an almost talismanic aura about his working script for the film. Scribbled on the back page, with Brando's frequent misspellings and typical crosshatches, is a list of notes about how to play Don Corleone and about his character's sons Michael and Sonny:

# through the nose

# High voice

# Nose broken early in youth to account for difficulties

# Mihecl's discision to kill

# Broken nose Sonny

Although he later sneered that he made films only for money, Brando's notes about characters appear even on scripts for late, lesser movies like "The Score," from 2001. For "Mutiny on the Bounty" there are such voluminous annotations on many versions of the script, and so many obsessive notes about the production (a notoriously troubled, overbudget shoot) that you can practically see him spinning out of control. (There are no scripts here from the 1950's films that established him and inspired generations of actors, like "A Streetcar Named Desire," "The Wild One" and "On the Waterfront.")

Many of the letters he received are illuminating, too. There is the irresistibly understated, handwritten note from Puzo that begins, "I wrote a book called THE GODFATHER," and goes on, "I think you're the only actor who can play the Godfather with that quiet force and irony the part requires." The note was sent even before Mr. Coppola made the famous screen test in which Brando stuffed toilet paper in his cheeks to transform himself.

In a long typewritten letter, Kerouac asks Brando to "buy ON THE ROAD and make a movie of it." He adds, "you play Dean and I'll play Sal." Too bad that potentially hilarious buddy movie was never made.

And there is a letter from Mr. Coppola about "Apocalypse Now" (which made the troubled "Mutiny" seem like a breeze), in which he struggles to make sense of Brando's character, Kurtz, then called Leighley.

These papers are much more than Hollywood trinkets, and they belong in a library or archive where they would be available to film historians and biographers. But all the film material Brando left behind will be auctioned. Through a spokesman, the estate's executors said that "within the will, there was no provision for any charitable donation," meaning they couldn't have donated anything if they had wanted to. Brando didn't specify what should be done with his papers, either, apparently content to let the myth go where it would.

Christie's estimate for the sale is modestly given as "in excess of $1 million." But celebrity auctions routinely surpass the estimates, which don't account for the passion some fans can bring to anything in a movie star's orbit. Christie's is guessing that someone will pay $4,000 to $6,000 for the black tunic that Brando wore as Jor-El in "Superman," $300 to $500 for two of his driver's licenses from the 1990's, $600 to $800 for (no kidding) an exercise machine. For Brando, so cynical about his fame, getting the public to buy his old stuff might be his final practical joke.

The Personal Property of Marlon Brando auction will begin at noon on Thursday at Christie's, 20 Rockefeller Plaza, Manhattan, where the 320 lots of stage, screen and personal objects can be viewed starting tomorrow and continuing through Wednesday. Information: (212) 636-2000.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections XML Help Contact Us Work for Us Back to Top