Wednesday, May 18, 2005

May 16, 2005

60 Years Later, Debating Yalta All Over Again

By ELISABETH BUMILLER

WASHINGTON

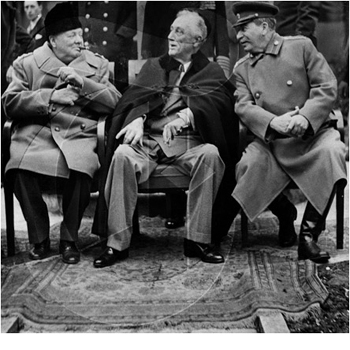

When President Bush declared on May 7 in Latvia that the 1945 Yalta agreement led to "one of the greatest wrongs of history," he reignited an ideological debate from the era of Joseph McCarthy. For more than a week now, the left and the right have been arguing over the president's words and rearguing the deal made by Franklin D. Roosevelt, Joseph Stalin and Winston Churchill in an old czarist resort near the Crimean city of Yalta in the closing days of World War II.

Mr. Bush has criticized Yalta at least six other times publicly, usually in Eastern Europe, but never so harshly. In the dust kicked up by the quarreling, the central questions for White House watchers are these: How did the unexpected attack on Yalta get in the president's speech? What drove his thinking? Did the White House expect the fallout?

First, the history and the debate.

Yalta effectively recognized Soviet hegemony in Eastern Europe, and set the stage for what later became known as the cold war. In the view of many conservatives, the dying Roosevelt did nothing less at Yalta than sell out Eastern Europe to Soviet control for the next 50 years. In the view of liberals, including major historians, Roosevelt ceded Poland and parts of Eastern Europe to Stalin because the Red Army controlled the territory anyway, and Yalta changed no realities on the ground. Yalta also called for free elections in Poland, which Stalin later ignored.

Mr. Bush not only sided with the conservatives in his speech in the Latvian capital, Riga, but he also took a harder-line view against Yalta than any other American president, including Ronald Reagan. By far Mr. Bush's most hotly contested formulation was his assertion that Yalta followed in the "unjust tradition" of the secret nonaggression deal between the Nazis and the Soviets known as the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact and the British appeasement of Hitler in the Munich pact.

"Which is a bit much," said John Lewis Gaddis of Yale, a leading historian of the cold war. "Munich and the Nazi-Soviet pact caused things to happen. Yalta didn't change anything. If the Yalta conference had never taken place, the division of Europe into two great spheres of influence would still have happened."

Robert Dallek, a Boston University historian and an expert on Roosevelt's foreign policy, agreed. "Republicans have been beating on this issue since the end of the Roosevelt presidency, and they have been consistently off the mark," he said. "This idea that Roosevelt and Churchill gave away Eastern Europe to the Soviets is nonsense."

David M. Kennedy, a Stanford historian, put it this way: "This was a stick to beat the Democrats up with in the McCarthy era."

Conservatives are equally adamant. In his syndicated column last Wednesday, Patrick J. Buchanan said that Mr. Bush told "the awful truth" about who really triumphed in World War II east of the Elbe - "it was Stalin, the most odious tyrant of the century" - and that the pact that Roosevelt and Churchill co-signed at Yalta was a "monstrous lie."

On the same day, Anne Applebaum, a columnist for The Washington Post, wrote that "a small crew of liberal historians and Rooseveltians have leaped to argue that the president was wrong." In fact, she said, Yalta and other wartime deals "went beyond mere recognition of Soviet occupation and conferred legality and international acceptance on new borders and political structures."

At the White House, Mr. Bush's speech was written by Michael Gerson, the assistant to the president for policy and strategic planning and the former chief speechwriter who still has a big hand in Mr. Bush's major addresses. The language in Mr. Gerson's Latvia speech that Yalta, in an "attempt to sacrifice freedom for the sake of stability" left a continent "divided and unstable," built on steadily intensifying language over the previous four years.

In June 2001 in Warsaw, Mr. Bush said, "Yalta did not ratify a natural divide, it divided a living civilization." In November 2002 in Lithuania, he declared that there would be "no more Munichs, no more Yaltas." In May 2003 in Krakow, he said, "Europe must finally overturn the bitter legacy of Yalta." This February in Brussels, Mr. Bush said, "The so-called stability of Yalta was a constant source of injustice and fear."

An administration official said on Friday that in the discussions about Mr. Bush's address - the president typically gives his speechwriters big-picture thematic direction and then has a heavy hand in the editing - the goal was to make the point that "countries need to look at their pasts." In this case, the White House wanted to make the point that President Vladimir V. Putin of Russia, Mr. Bush's host the following day, should apologize for the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact, which led to the Soviet annexation of Latvia and the other Baltic states.

So Mr. Bush's assertion of American failure at Yalta was viewed at the White House as a model for what Mr. Putin should - but did not - do. It was also a poke in the eye to the Russians, salve to Mr. Bush's Baltic hosts and an effort to contrast what Mr. Bush promotes as his uncompromising vision for democracy in the Middle East with what he sees as the expedience of the past.

The administration official, who requested anonymity because he said he wanted to let the president's words speak for themselves, said the White House had not anticipated last week's fallout, nor had anyone there discussed what he called the "nasty and stupid" Yalta politics of the McCarthy era.

"The point was, it was a lousy agreement," the official said.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Contact Us Back to Top