Wednesday, May 11, 2005

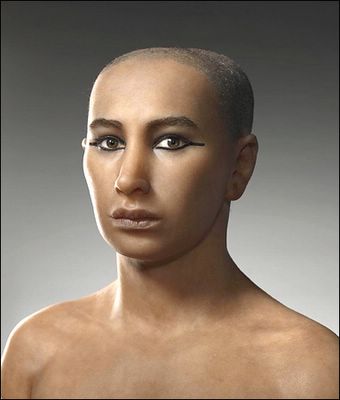

Egyptian Supreme Council of Antiquities/National Geographic Society

Teams of artists and scientists, using computer scans to reconstruct the face of King Tut, say he had buck teeth and a long skull.

May 11, 2005

Tut Was Not Such a Handsome Golden Youth, After All

By JOHN NOBLE WILFORD

Artists and scientists drawing on a detailed examination of King Tut's mummy have reconstructed the face of the young ruler as he might have looked in life: an unusually elongated skull, a narrow face, pronounced lips and possibly a receding chin.

Pictures of Tutankhamen's reconstructed face and head were released yesterday by Dr. Zahi Hawass, secretary general of the Supreme Council of Antiquities in Cairo. The new photos presented an apparently more realistic depiction of Tut than the stylized image of him on his golden burial mask.

"The shape of the face and skull," Dr. Hawass said in a statement, "are remarkably similar to a famous image of Tutankhamen as a child, where he is shown as the sun god at dawn rising from a lotus blossom."

The reconstructions were based on the most thorough examination yet of Tut's mummy, including 1,700 three-dimensional images taken in January with computed tomography, or CT scans. The pictures of the skull, bones and soft tissues, more revealing than ordinary X-rays, were the latest of the Tut mummy's encounters with curious scientists and their modern technology since its discovery in 1922.

Tutankhamen died at 19, too soon to have given much thought to the hereafter. But he must have shared his royal predecessors' belief in an afterlife befitting rulers of ancient Egypt, an eternity with all of life's pleasures enjoyed in the company of the gods. Still, his has been an afterlife he could never have imagined.

The discovery of Tut's tomb in the Valley of the Kings at Luxor was one of the archaeological sensations of the 20th century. The treasures buried with him have drawn throngs to exhibitions, making him the most celebrated of pharaohs. His mummy was X-rayed twice, more than three decades ago, and the results heightened speculation about his untimely death: whether he died of natural causes or was murdered.

Now three independent teams of artists and scholars, one French, one American and one Egyptian, have used the CT images to reconstruct Tut's face, which Dr. Hawass said was the best preserved part of the mummy. The French and Egyptian teams were told the subject was Tutankhamen; the American team was working blind.

The teams essentially agreed on the proportions of the skull, the basic shape of the face and the size and setting of the eyes. They differed on the shape of the nose and ears, which have not held up well. The American and French versions showed a weak chin, while the Egyptians gave Tut a stronger one.

Dr. Hawass said the Egyptian team's version "looks the most Egyptian."

Before the artists began their work, Egyptian and international experts in anatomy, pathology and radiology, led by Dr. Madiha Khattab, dean of medicine at Cairo University, spent two months analyzing the CT images.

They concluded, for example, that Tut's elongated skull was a normal anthropological variation, not a result of disease or congenital abnormality. They noted his thin face and pronounced overbite - buck teeth. Egyptologists said overbites ran in his family, like the Hapsburg lip of more recent royal history.

Tut also had large lips, a receding chin and a small cleft in the roof of his mouth. The examiners said the cleft palette did not appear to have affected his external expression in any way.

All in all, the science team said, Tut appeared to have been in good health until he died. Judging from the bones, he was well-fed and there were no signs of malnutrition or disease in childhood. His teeth, except for an impacted wisdom tooth, were in excellent condition. He was slightly built and probably stood 5½ feet tall.

So why did Tut die so young, around 1325 B.C.?

An X-ray in 1968 revealed a hole at the base of Tut's cranium. Some Egyptologists suspected he was murdered, possibly by his successor, Ay.

On a recent visit to the University of Pennsylvania, however, Dr. Hawass said the scientists who analyzed the CT images found no apparent evidence of foul play. They said the damage to the cranium was apparently caused when the mummy's discoverers pried the burial mask from the head.

"No one hit Tut on the back of the head," Dr. Hawass said, though he conceded that he could have been poisoned. But to establish that would require other lines of analysis. He also speculated that the broken leg that Tut is known to have suffered days before he died could have become infected and contributed to his death.

The application of CT imaging to mummy research is becoming widespread. Egypt is scanning all the royal mummies in the Cairo Museum. Last week Stanford performed CT scans on the mummy of an Egyptian child. Bowers Museum in Santa Ana, Calif., recently conducted similar research on seven mummies on loan from the British Museum.

Not coincidentally, the re-examination of the Tut mummy and the release of the images of the reconstructed head coincided with promotions of a new exhibition, "Tutankhamen and the Golden Age of the Pharaohs." It opens June 16 at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art and will later move to Fort Lauderdale, Fla., Chicago and Philadelphia.

The show was organized by the Egyptian antiquities council and the National Geographic Society, which will feature the Tut reconstruction in the June issue of its magazine.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company Home Privacy Policy Search Corrections RSS Help Contact Us Back to Top