Tuesday, March 29, 2005

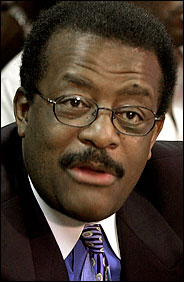

Johnnie L. Cochran Jr

Johnnie Cochran, Famed Defense Lawyer, Is Dead at 67

By ADAM LIPTAK

LOS ANGELES -- Johnnie L. Cochran Jr., who became a legal superstar after helping clear O.J. Simpson during a sensational murder trial in which he uttered the famous quote "If it doesn't fit, you must acquit," died Tuesday. He was 67.

Cochran died of a brain tumor at his home in Los Angeles, his family said.

"Certainly, Johnnie's career will be noted as one marked by 'celebrity' cases and clientele," his family said in a statement. "But he and his family were most proud of the work he did on behalf of those in the community."

With his colorful suits and ties, his gift for courtroom oratory and a knack for coining memorable phrases, Cochran was a vivid addition to the pantheon of America's best-known barristers.

The "if it doesn't fit" phrase would be quoted and parodied for years afterward. It derived from a dramatic moment during which Simpson tried on a pair of bloodstained "murder gloves" to show jurors they did not fit. Some legal experts called it the turning point in the trial.

Soon after, jurors found the Hall of Fame football star not guilty of the 1994 slayings of his ex-wife Nicole Brown Simpson and her friend Ronald Goldman.

Simpson, reached at his home in Florida, praised Cochran on Tuesday, saying "I don't think I'd be home today without Johnnie."

He said other members of his defense team also deserved credit for his acquittal, but added: "Without Johnnie running the ball, I don't think there's a lawyer in the world that could have run that ball. I was innocent, but he believed it."

For Cochran, Simpson's acquittal was the crowning achievement in a career notable for victories, often in cases with racial themes. He was a black man known for championing the causes of black defendants. Some of them, like Simpson, were famous, but more often than not they were unknowns.

"The clients I've cared about the most are the No Js, the ones who nobody knows," said Cochran, who proudly displayed copies in his office of the multimillion-dollar checks he won for ordinary citizens who said they were abused by police.

"People in New York and Los Angeles, especially mothers in the African-American community, are more afraid of the police injuring or killing their children than they are of muggers on the corner," he once said.

By the time Simpson called, the byword in the black community for defendants facing serious charges was: "Get Johnnie."

Over the years, Cochran represented football great Jim Brown on rape and assault charges, actor Todd Bridges on attempted murder charges, rapper Tupac Shakur on a weapons charge and rapper Snoop Dogg on a murder charge.

He also represented former Black Panther Elmer "Geronimo" Pratt, who spent 27 years in prison for a murder he didn't commit. When Cochran helped Pratt win his freedom in 1997 he called the moment "the happiest day of my life practicing law."

But the attention he received from all of those cases didn't come remotely close to the fame the Simpson trial brought him.

After Simpson's acquittal, Cochran appeared on countless TV talk shows, was awarded his own Court TV show, traveled the world over giving speeches, and was endlessly parodied in films and on such TV shows as "Seinfeld" and "South Park."

In "Lethal Weapon 4," comedian Chris Rock plays a policeman who advises a criminal suspect he has a right to an attorney, then warns him: "If you get Johnnie Cochran, I'll kill you."

The flamboyant Cochran enjoyed that parody so much he even quoted it in his autobiography, "A Lawyer's Life."

"It was fun. At times it was a lot of fun," he said of the lampooning he received. "And I knew that accepting it good-naturedly, even participating in it, helped soothe some of the angry feelings from the Simpson case."

Indeed, the verdict had done more than just divide the country along racial lines, with most blacks believing Simpson was innocent and most whites certain he was guilty. It also left many of those certain of Simpson's guilt furious at Cochran, the leader of a so-called "Dream Team" of expensive celebrity lawyers that included F. Lee Bailey, Robert Shapiro, Barry Scheck and Peter Neufeld.

But in legal circles, the verdict represented the pinnacle of success for a respected attorney who had toiled in the Los Angeles legal profession for three decades.

Cochran was born Oct. 2, 1937 in Shreveport, La., the great-grandson of slaves, grandson of a sharecropper and son of an insurance salesman. He came to Los Angeles with his family in 1949, and became one of two dozen black students integrated into Los Angeles High School in the 1950s.

Even as a child, he had loved to argue, and in high school he excelled in debate.

He came to idolize Thurgood Marshall, the attorney who persuaded the U.S. Supreme Court to outlaw school segregation in the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education decision and who would eventually become the Supreme Court's first black justice.

"I didn't know too much about what a lawyer did, or how he worked, but I knew that if one man could cause this great stir, then the law must be a wondrous thing," Cochran said in his book. "I read everything I could find about Thurgood Marshall and confirmed that a single dedicated man could use the law to change society."

After graduating from UCLA, Cochran earned a law degree from Loyola University. He spent two years in the Los Angeles city attorney's office before establishing his own practice, later building his firm into a personal injury giant.

His first marriage, to his college sweetheart, Barbara Berry, produced two daughters, Melodie and Tiffany. During their divorce, it came to light that for 10 years Cochran had secretly maintained a "second family," which included a son.

When that relationship soured, his mistress, Patricia Sikora, sued him for palimony and the case was settled privately in 2004.

Although he frequently took police departments on in court, Cochran denied being anti-police and supported the decision of his only son, Jonathan, to join the California Highway Patrol.

He counted among his closest friends Los Angeles City Councilman Bernard Parks, the city's former police chief, and the late Mayor Tom Bradley, who had been a Los Angeles police lieutenant before going into politics.

But in the Simpson case, Cochran turned the murder trial into an indictment of the Police Department, suggesting officers planted evidence in an effort to frame the former football star because he was a black celebrity.

By the time Simpson was acquitted, Cochran and co-counsel Shapiro were on the outs. Shapiro, who is white, had accused Cochran of playing the race card and of dealing it "from the bottom of the deck."

Simpson, meanwhile, was held liable for the killings following a 1997 civil trial and ordered to pay the Brown and Goldman families $33.5 million in restitution. Cochran didn't represent him in that case.

He remained a beloved figure in the black community, admired as a lawyer who was relentless in his pursuit of justice and as a philanthropist who helped fund a UCLA scholarship, a low-income housing complex and a New Jersey legal academy, among other charitable endeavors.

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top