Thursday, March 31, 2005

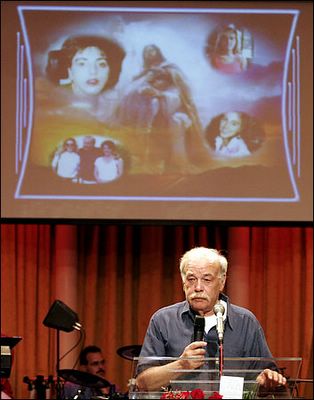

Bob Schindler spoke at a memorial service for his daughter, Terri Schiavo, on Thursday evening.

Schiavo's Case May Reshape American Law

By SHERYL GAY STOLBERG

WASHINGTON, March 31 - The life and death of Terri Schiavo - intensely public, highly polarizing and played out around the clock on the Internet and television- has become a touchstone in American culture. Rarely have the forces of politics, religion and medicine collided so spectacularly, and with such potential for lasting effect.

Ms. Schiavo, the profoundly incapacitated woman whose family split over whether she would have preferred to live or die, forced Americans into a national conversation about the end of life. Her case raised questions about the role of government in private family decisions.

But her legacy may be that she brought an intense dimension - the issue of death and dying - to the battle over what President Bush calls "the culture of life."

Nearly 30 years after the parents of another brain-damaged woman, Karen Ann Quinlan, injected the phrase "right to die" into the lexicon as they fought to unplug her respirator, Ms. Schiavo's case swung the pendulum in the other direction, pushing the debate toward what Wesley J. Smith, an author of books on bioethics, calls " the right to live."

"This is the counterrevolution," said Mr. Smith, who has been challenging what he calls the liberal assumptions of most bioethicists. "I have been frustrated at how difficult it is to bring the starkness of these issues into a bright public discussion. Schiavo did it."

Experts say that unlike the Quinlan case, which established the concept that families can prevail over the state in end-of-life decisions, the Schiavo case created no major legal precedents. But it could well lead to new laws. Already, some states are considering more restrictive end-of-life measures like preventing the withdrawal of a feeding tube without explicit written directions.

That troubles some medical ethicists and doctors.

"I am concerned about the erosion of a very hard-won multiple-decade process of agreeing that these decisions belong inside families," said Dr. Diane E. Meier, an expert in end-of-life care at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine in New York. "We've always said that autonomy and self-determination does not trump the infinite value of an individual life, that people have the right to control what is done to their own body. I think that is at risk."

For social conservatives who argue that sanctity of life trumps quality of life, Ms. Schiavo came along at the right place and time, at a moment of their ascendancy in American politics. The election last November kept Mr. Bush in the White House and gave Republicans firmer control of Congress, particularly in the Senate, where conservatives gained several seats.

Among those conservative freshmen is Senator Mel Martinez, Republican of Florida, who prodded Congress to pass a bill allowing a federal court to review the Schiavo case. The move prompted a backlash, with polls showing an overwhelming majority of Americans opposed to it, though there is no way to assess whether that sentiment will have lasting political effects.

"I am amazed by the attention and the passions that have been aroused by this," Mr. Martinez said. "It may be one of those issues that touches families, that transcends the cultural wars."

Others say that far from transcending the cultural wars, Ms. Schiavo's case landed smack in the middle of them.

"It may be that her legacy is to set off an ongoing debate in American public policy about the sanctity of life and how we are going as a society to make decisions about when life begins, when it ends and what protections it ought to have," said Gary L. Bauer, president of American Values, a conservative group.

That language percolates through other debates that involve clashes of medicine, politics and religion like the fights over abortion and embryonic stem cell research.

Tony Perkins, president of the Family Research Council, a Christian conservative group, drew the connection in an e-mail message to backers who mourned Ms. Schiavo.

"We often hear about the culture of life that we are trying to protect," Mr. Perkins wrote, "yet rarely do we talk about the culture of death."

Ms. Schiavo brought these ideas home in a deeply personal way. Her history had a captivating narrative arc and a compelling cast of characters. The patient: Ms. Schiavo, who had lingered for 15 years in what doctors describe as a "persistent vegetative state." The husband: Michael, painted by some as a villainous adulterer as he sought to have her feeding tube withdrawn. The parents: Robert and Mary Schindler, determined to keep their daughter alive.

As the drama unfolded, television viewers could watch Ms. Schiavo on videotape and make a judgment.

"The closest thing to it, but not quite as poignant, are the debates about stem cell research," said Marshall Wittmann, a senior fellow at the Democratic Leadership Council, who became familiar with conservative politics when he worked for the Christian Coalition. "But they deal with diseases that touch upon every family, but not a single individual."

The debate also exposed fissures among Republicans, pitting social conservatives who framed the debate around preserving life against those who favor states' rights and limited government. "There was a philosophical train wreck," Mr. Wittmann said.

The case also fueled conservatives' anger over what they regarded as a runaway judiciary, laying the groundwork for future fights over Mr. Bush's judicial nominees.

"It shows just how much power the courts have usurped from the legislative and executive branches," Mr. Perkins said, "that they now hold within their hands the power of life and death."

The courts have been weighing in on such issues for years. One of the first major cases was in 1976, with Ms. Quinlan. The New Jersey Supreme Court permitted her parents to turn off her respirator.

In 1990, in the case of another brain-damaged woman, Nancy Cruzan, the United States Supreme Court recognized for the first time a right to forgo unwanted treatment. In 1997, Oregon passed an assisted suicide law, letting doctors prescribe lethal doses of medication to terminally ill patients. The Supreme Court has agreed to hear the Bush administration's challenge to the law.

In all these battles, the common theme was that medical technology had run amok, stripping patients of their dignity at the end of their lives.

"In the classic cases around death and dying, they were again and again efforts by families to get the patient out of the medical grip," said David J. Rothman, director of the Center for the Study of Society and Medicine at Columbia University.

The Schiavo case, Professor Rothman said, is "really the effort to force physicians to intervene, rather than force them to desist."

"So you've got a shift here," he said.

That shift made for odd bedfellows. Ralph Nader, the consumer advocate, joined Mr. Smith, the bioethicist, in calling for legal action "to let Terri Schiavo live." Advocates for disability rights prompted Democrats like Senator Tom Harkin of Iowa to take up her cause.

Mr. Martinez, who said his sister suffered a brain disorder that left her unable to communicate at the time she died, called it "a beautiful moment of coming together for a sick and disabled person." He said he intended to work with Mr. Harkin to press Congress to "provide an avenue of due process and legal recourse which may not exist today" for patients like Ms. Schiavo.

Around the country, state lawmakers are contemplating changes, as well. The Alabama Starvation and Dehydration Prevention Act would bar the withdrawal of a feeding tube without explicit written instructions. A lawmaker in Michigan is proposing a measure that would prevent an adulterer from making medical decisions for an incapacitated spouse.

Some medical ethicists say they are horrified. R. Alta Charo, a professor of law and bioethics at the University of Wisconsin, foresees a chilling effect on hospitals and doctors, who may become uncomfortable carrying out a patient's wishes against the backdrop of a family feud. Professor Charo said there was no way for lawmakers to predict all the permutations that play into decisions on death and dying.

"If you go back to Cruzan, the presumption was in favor of extending biological life," she said. "Over the last 30 years, the presumption has slowly shifted toward allowing people to die. What we are seeing is the counterinsurgency."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top