Thursday, March 31, 2005

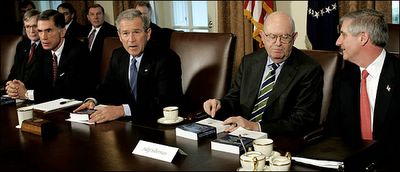

At a meeting this morning, President Bush was flanked by the men who led the commission. At left, Charles S. Robb. At right, Laurence H. Silberman.

Panel Says 'Dead Wrong' Data on Prewar Iraq Demands Overhaul

By DAVID STOUT

WASHINGTON, March 31 - The American intelligence community was "dead wrong" about Iraq's weapons arsenal in large part because of an outdated Cold War mentality and a vast, lumbering bureaucracy that continues to shackle dedicated and capable people, a presidential commission said today.

"The intelligence community must be transformed - a goal that would be difficult to meet even in the best of all possible worlds," the commission said in its report to President Bush. "And we do not live in the best of worlds."

The commission said the erroneous assumption by intelligence agencies that Saddam Hussein possessed deadly chemical and biological weapons had damaged American credibility before a world audience, and that the damage would take years to undo.

Only systemic changes in thinking and acting - changes that will surely bring discomfort to agencies and individuals - will bring the intelligence system to a point where it can cope with the dangers of the 21st century, the commission said. It said, too, that some recent attempts at change - notably the intelligence reorganization act that created the powerful position of national intelligence director - did not go far enough.

The panel, whose nine members included Democrats and Republicans, noted pointedly that three and a half years after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States had built mighty industrial and military forces that helped force Germany to its knees and were about to vanquish Japan. Three and a half years after Sept. 11, 2001, the panel said, there has been no comparable awakening of the intelligence bureaucracy to defeat a network of deadly, far more elusive foes.

The Sept. 11 attacks did lead to creation of the Department of Homeland Security, which absorbed a number of agencies in the biggest government reorganization in half a century. The commission report today called for further government changes, including a new counter-proliferation center to coordinate data throughout the intelligence bureaucracy on nuclear, biological and chemical weapons, and a reorganization of the Justice Department to enable one office, not several, to handle intelligence, counterintelligence and counterterrorism.

Other, more mundane changes were recommended: better training "at all stages of an intelligence professional's career," for instance, and a rethinking of the intelligence briefing given daily to the president. "The daily intelligence briefings given to you before the Iraq war were flawed," the commission stated, addressing Mr. Bush.

Despite some conspicuous successes, like exposing a nuclear-proliferation network run by a rogue Pakistani scientist and gathering significant data on Libya's arsenal, America's intelligence agencies are not keeping up with the deadly threats the country now faces, the panel concluded.

"There is no more important intelligence mission than understanding the worst weapons that our enemies possess, and how they intend to use them against us," the commission declared. "These are their deepest secrets, and unlocking them must be our highest priority."

President Bush said today he agreed that the intelligence bureaucracy "needs fundamental change," and he pledged to try to bring it about. "I asked these distinguished individuals to give me an unvarnished look at our intelligence community, and they have delivered," he said.

Copies of the report were distributed to members of Congress, and the lawmakers are certain to debate its findings, and what to do about them. The report, several hundred pages long, contains portions that are classified and were not made public.

Senator Pat Roberts, the Kansas Republican who heads the Senate Intelligence Committee, said he was pleased by the report. "I don't think there should be any doubt that we have now heard it all regarding prewar intelligence," Mr. Roberts told The Associated Press.

Representative Ike Skelton of Missouri, leading Democrat on the House Armed Services Committee, told The A.P. that the faults were obviously widespread. "I don't think you can blame any one person, although the buck does stop at the top of every one of these agencies," Mr. Skelton said.

President Bush created the commission, headed by Laurence H. Silberman, a senior federal appeals court judge, and Charles S. Robb, a former Virginia governor and senator, early in 2004. The presidential order directed the panel to investigate intelligence-gathering and analysis - not the use that policymakers made of the intelligence.

The false assumptions about Iraq's arsenal were not the result of deliberate distortion, nor were they influenced by pressure from outside the agencies, the Silberman-Robb commission said. Rather, it said, they came about because the intelligence bureaucracy collected far too little information, "and much of what they did collect was either worthless or misleading."

Moreover, the commission concluded, intelligence officials failed to make it clear to policymakers how deficient their information was.

Describing the intelligence bureaucracy as "fragmented, loosely managed and poorly coordinated," the commission said the government's 15 intelligence organizations "are a 'community' in name only and rarely act with a unity of purpose."

The panel, officially called the Commission on the Intelligence Capabilities of the United States Regarding Weapons of Mass Destruction, echoed some of the findings of earlier inquiries into American intelligence failures.

As did the 9/11 commission and the Senate Intelligence Committee, which also studied intelligence lapses leading up to the American-led war against Iraq, the Silberman-Robb commission singled out some of the most familiar entities in the bureaucracy - the Central Intelligence Agency and the Federal Bureau of Investigation - as well as the huge National Security Agency, much of whose function is electronic eavesdropping and analysis.

"The C.I.A. and N.S.A. may be sleek and omniscient in the movies, but in real life they and other intelligence agencies are vast government bureaucracies," the nine-member commission told the president.

"They are bureaucracies filled with talented people and armed with sophisticated technological tools, but talent and tools do not suspend the iron laws of bureaucratic behavior," the commission said. "The intelligence community is a closed world, and many insiders admitted to us that it has an almost perfect record of resisting external recommendations."

And despite the allusion to the talented people within the bureaucracies, the commission hinted that intelligence agencies need more diversity in their ranks, and new approaches to their jobs. "We need an intelligence community that is truly integrated, far more imaginative and willing to run risks, open to a new generation of Americans, and receptive to new technologies," the commission said. (Previous examinations of American intelligence agencies have said they need more people fluent in various languages, including Arabic.)

The F.B.I. has made progress in shifting itself into an intelligence-gathering organization, but "it still has a long way to go," the commission said. Moreover, it said, the intelligence reorganization act leaves the bureau's relationship to the new national intelligence director, John Negroponte, "especially murky."

The legislation that created Mr. Negroponte's position was fiercely debated on Capitol Hill. In the end, even though it invested the new national intelligence director with wide powers, those powers were still not as great as those envisioned by the commission that investigated the terror attacks of Sept. 11, 2001. That panel called for a director of national intelligence who would truly deserve the title "intelligence czar," as the post is known informally in Washington, and break down resistance to change.

"The D.N.I. cannot make this work unless he takes his legal authorities over budget, programs, personnel and priorities to the limit," the commission said. "It won't be easy to provide this leadership to the intelligence components of the Defense Department, or to the C.I.A. They are some of the government's most headstrong agencies. Sooner or later, they will try to run around - or over - the D.N.I."

Mr. Negroponte, a former ambassador to the United Nations and to the new Iraq, is no stranger to the ways of Washington.

Response to the report on Capitol Hill came quickly from Senator John Kerry, Democrat of Massachusetts, who rekindled themes from his failed presidential bid last year.

"This is much more than a wake-up call," he said in a statement. "Not only was the intelligence dead wrong about Iraq, but with growing threats in Iran and North Korea, we must take deadly seriously the commission's conclusion that we know disturbingly little about the weapons programs of hostile nations."

"We need accountability and action, immediately," he added. "The president has enormous work to do to restore the credibility of American intelligence gathering, and the administration must start catching up now."

The Silberman-Robb panel sought to avoid a condemning tone. "We have been humbled by the difficult judgments that had to be made about Iraq and its weapons programs," it said at one point. "We are humbled too by the complexity of the management and technical challenges intelligence professionals face today."

Nevertheless, the commission's findings are likely to stoke the smoldering debates over the war in Iraq, whose main rationale was supposedly to neutralize the danger from Saddam Hussein's deadly weapons. And it will also stir new talk about whether architects of the Iraq policy - Defense Secretary Donald H. Rumsfeld; his deputy, Paul D. Wolfowitz; former national security adviser Condoleezza Rice, who is now secretary of state; and the former C.I.A. chief George J. Tenet - should have had to answer for mistaken assumptions.

Administration critics have said Mr. Rumsfeld should have been dismissed instead of being kept on as Pentagon chief, that Ms. Rice should not have been made secretary of state, and that Mr. Tenet should have gone into retirement without the Medal of Freedom bestowed on him by President Bush. The critics have also voiced anger over the choice of Mr. Wolfowitz to head the World Bank - a position in which he was installed today.

Despite the somber, alarming tone of the commission report, Mr. Silberman and Mr. Robb expressed optimism that improvements can be wrought. "It's a whole lot easier to instigate change when there is a major change in leadership taking place," Mr. Robb said, referring to Mr. Negroponte's nomination as national intelligence director and his approaching Senate confirmation.

"Was the war against Iraq a waste?" they were asked at a news briefing.

Mr. Silberman said that was a policy issue and "we didn't deal with policy."

Copyright 2005 The New York Times Company | Home | Privacy Policy | Search | Corrections | RSS | Help | Back to Top